A Cinephile ‘Down Under’

What is an Australian cinephile today?

In his essay ‘No Flowers for the Cinephile (1987)’, recently re-published in a collection of writings entitled Mysteries of Cinema, Australian film writer Adrian Martin finds himself ruminating on the history of cinephilia in Australia. Read today, the piece provides a gateway into considering the contemporary ecology or landscape of cinephilia, both in Australia and beyond. Martin writes extensively about Australian cinephilia’s debt to cultural imperialism, using the term “Americanism” to define a “general love of or desire for cinema, [which] is more specifically constituted by a fixation on American (Hollywood) cinema.” Until government intervention in the late 60s, Australia had a floundering film industry, producing a minuscule output of films, which partly explains why film in the continent has such a rich history of unflinching adoption of American cinema and culture. The cinephile ‘down under’ therefore faces multiple challenges, chief among them the question of what exactly might constitute an Australian national cinema.

Also wrapped inside Martin’s essay is the task of providing a degree of self-recognition or definition within the Australian cultural landscape for what actually constitutes a cinephile. Martin writes that it cannot be found in the pages of a 1979 anthology such as Australian Popular Culture. Nor is it present in the cultural critique of an author like Donald Horne, who describes the “suburbanite” in books like The Lucky Country without any mention of Australian cinephilia. The flowers of Martin’s title refer to a cinephile who, as examined in the piece, exists within the confines of a dark room living out their fantasies. There, the cinema is a space of death and communion, precisely the two occasions when flowers are offered as tokens of symbolic jest: the funeral and the wedding. But these flowers (and their absence) are also symbolic of the acknowledgement Martin believes is owed to cinephiles in Australia, yet still, at the time of writing, not given. Through an erudite study of trans-national film histories, he places the Australian cinephile under the contrasting cultural umbrellas of British magazines like Screen and French magazines like Paris-based Cahiers Du Cinema and Lyon-centred Positif. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, it was from international film literature that the Aussie cinephile took his or her cue.

But Cinephilia had shifted dramatically between the 1960s and the 1980s, the period traced in Martin’s essay. Citing David Will’s writing from 1982 in Framework, Martin emphasises his point that the majority of the cinephile landscape in Britain in the 1960s (Peter Wollen, Alan Lovell and Geoffrey Nowell-Smith) was affiliated with the Marxist-oriented magazine New Left Review where writers were obsessed with American cinema out of an “anti-colonialist” desire. The assumption indeed was that critiquing and over-analysing Hollywood cinema could dismantle it or highlight its failings. However, in 1982, Will reflected that “we on the left no longer require these demands to be met in this way,” thus signalling an end of cinephilia’s de facto embrace of American cinema. If sentiment could shift so greatly in only twenty years, where are we left now, forty years on from No Flowers’ original publication?

***

In correspondence with me, Martin points out what he believes constitutes cinephilia today. For him, “[cinephilia] is more a counter-culture, an underground culture — or, at least, it tries to be. It's against 'official' taste, mass taste.” He goes on to explain that whilst American cinema has been and continues to be influential in Australia, “it wasn't Star Wars or Spielberg or Casablanca that [cinephiles] celebrated — it was the more contentious stuff, Samuel Fuller, Walter Hill.” This is an important distinction, one which Martin addresses in his 2008 essay ‘Cinephilia as War Machine,’ in which he attempts to provide a fresh definition of cinephilia forty years on from ‘No Flowers’. He writes that cinephilia is typified by somebody who “[hates] the official cinema of their own country, the boring mainstream — that’s the war machine in action.”

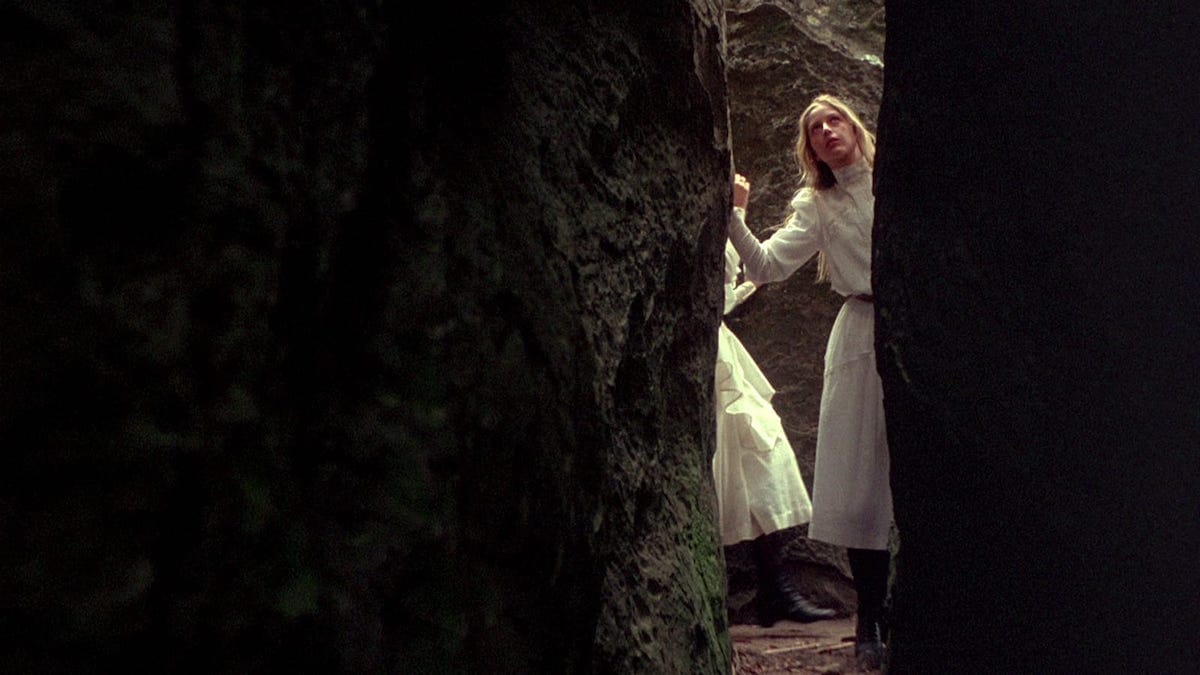

From a conditional but intense embrace of American cinema to its rejection, from a defense of national cinema against the tide of American dominance to the dismissal of national cinema — where does this leave Australian cinephilia today? How do I, an Australian cinephile, grapple with the official cinema of my homeland? It is important to first define the traditional narrative of the Australian film industry, which is commonly thought to have begun in 1969 with the advent of Prime Minister John Gorton and his promise to establish a film and television school (Australian Film Television Radio School), a government film funding commission (Australian Film and Development Commission / Australian Film Commission) and, later the Experimental Film and Television Fund (EFTF). Soon after, the Labor opposition party was elected together with Gough Whitlam, a leader who was considered to be culturally conscious. A large output of movies ensued and new genres unto themselves came to be defined, such as the “AFC film,” an unofficial term often attached to historical period dramas set in the bush. These films, which included Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), Gillian Armstrong’s My Brilliant Career (1979) and Weir’s The Year of Living Dangerously (1982), were characterised by the desire of white Australia to see itself reflected on the big screen.

Out of this landscape emerged the Melbourne based journal Cinema Papers, a government-initiated magazine founded in 1974 whose mission statement was akin to the UK’s Sight and Sound. In it, one could read the latest news and feature interviews predominantly about the endeavours of mainstream Australian film creatives. Sydney’s Filmnews mirrored Cinema Papers in its mission and goals. Less mainstream publications cropped up too, such as Martin’s self-edited Buff, or Stuffing, created by musician / filmmaker / writer Philip Brophy, though the latter was in fact supported by the government. Other similar outlets were Antony I. Ginnane’s short-lived Film Chronicle magazine and Corinne and Arthur Cantrill’s Filmnotes, established in 1971.

Such publications form a long tradition which influenced the ACMI (Australian Centre for the Moving Image) funded, Berlin / Melbourne based publication press Fireflies. Funded in 2014, Fireflies initially drew on the auteur principle, assigning each opposing side of the magazine to a different auteur director— one issue, for example, pairs Ben Rivers with Pedro Costa. However, Fireflies’ latest series, called Decadent, is a nod in a different direction. The series consists of several books written by distinguished international film critics, each about one influential film from each year of the first decade of this century. So far, Nick Pinkerton has tackled Tsai Ming-liang’s 2003 film Goodbye, Dragon Inn while Erika Balsom has written about James Benning’s 2004 experimental film Ten Skies. Also announced are Dennis Lim on Hong Sangsoo’s Tale of Cinema (2005), Melissa Anderson on David Lynch’s Inland Empire (2006) and Rebecca Harkins-Cross on Lucrecia Martel’s The Headless Woman (2008). The release of each new book is accompanied by a screening of the film at ACMI and other cinematic spaces around the world. With the pronounced effort and the time and energy spent producing each book, Fireflies aims to quell the indefatigable wave of content that much film writing has become, in Australia and around the world. Besides encouraging a slower and deeper relationship to cinema than that promoted by the repurposed PR click-bait that dominates film discussion online, the publishing press also provides its authors with relatively free rein to write whatever they would like. While Balsom’s book touches on the nature of film writing itself, Pinkerton’s text on Goodbye, Dragon Inn engages with the definition of cinephilia specifically, delving into what he perceives to be one of its key components: a nostalgia for and about cinema itself.

Nick Pinkerton centres his book firmly around the notion of nostalgia and how Tsai Ming-liang grapples with it throughout his filmography, but particularly in Goodbye, Dragon Inn. The author traces Tsai’s childhood in Malaysia in a town called Kuching, where Tsai was able to satisfy a healthy appetite for films at what were historically single-theatre cinemas. The landscape changed once he moved to Taiwan in his 20s, but he discovered the Fu-Ho Grand Theatre, a neighbourhood complex which housed a single-screen cinema and on which Goodbye is based. Midway through his book, Pinkerton describes a recurring dream Tsai had for forty years of a cinema known as the Odeon. Pinkerton argues that the cinema is almost certainly the Cathay from Tsai’s hometown, one in which Tsai evocatively describes watching Ying Yunwei’s 1959 film Chasing the Spirit. Of these theatres, only memories remain: they were cleared and some converted into multi-storey car parks as the twentieth century progressed.

Pinkerton discusses the filmmaker’s nostalgia extensively in order to better highlight similar feelings of his own. He writes, for example, of a place in suburban Cincinnati where “the big houses…were vivisected for multiplexing…[and] suburban ‘plexes sprouted like toadstools in the middle of vast parking lots.” Pinkerton reiterates that whilst his and Tsai’s experiences are poles apart, “nostalgia of this sort is indifferent to such indistinctions”— which leaves one wondering about the role nostalgia plays for cinephiles in reconciling their subsummation in other cultures. Indeed, while Pinkerton and Tsai’s nostalgia is comparatively different in location and era, Pinkerton’s quote highlights the fact that cinephilia isn’t necessarily restricted by borders and nationality. Additionally, Martin was always conscious of cinephilia’s orientation towards other national cinemas, and hence away from a country’s own culture — an argument most easily demonstrated in the French New Wave’s obsession with Hollywood in the 1950s and 60s.

The difficulty in being a cinephile today therefore comes not so much from questions of nationality and borders, but from that of where exactly a cinephile may fit within an increasingly marginalised culture. For example, you may know all about the latest Tsai Ming-liang movie and regularly attend the local cinematheque at ACMI on Wednesday nights. But when it comes to explaining this obsession at a family Christmas dinner, how do you deal with the likely fact that no one present will know what you’re talking about? Cinephilia’s apparent marginalisation is not a new phenomenon. Rather, the pace at which this marginalisation is accelerating is.

In No Flowers, Martin raises this point further, stating towards the end of his essay, “what the cinephile feels is hopefully not so different from what the mass of people experiences when they take themselves to the movies in search of an experience of the senses and emotions.” The era which Martin evokes — that of the 1970s and 1980s — still featured a healthy number of repertory theatres (The Astor and The Valhalla in Melbourne, for example), drive-in cinemas and student-led theatres, reflecting the fact that people who may not have described themselves as cinephiles were watching films with regularity. Not so today — Martin’s quote stresses the expanding discrepancy between film and popular culture which has accelerated since the article’s publication forty years ago. Pinkerton’s nostalgia for multiplexes, meanwhile, crucially highlights how different the capacity to keep up to date with new cinema used to be, even back at the time of his own childhood.

In a 2016 article for Film Comment, contributor Kent Jones discusses the “marginalisation of cinema,” arguing that studio filmmaking together with modes of consumption are shifting. According to Jones, film cultures no longer produce the same amount of good films they once did, leaving cinema as a marginalised art form: “the measure of a vibrant, living cinema culture is not the number of great films being made, which is always small, but the number of good ones.” Meanwhile, cinema itself is “in the process of being culturally marginalized, which means that it is assuming a proud place alongside poetry, dance, and concert music.” In short, cinema is becoming more of a high art, one which is treated with a degree of reservation and uncertainty by cinemagoers, whereas it once felt like a mainstream medium.

This is a challenge which Fireflies and other cinephiles are attempting to overcome today. Through writing more personal and accessible than it is academic, the publishing press and magazine aims to provide more people with access to what might be deemed sophisticated or art house cinema. Pinkerton’s book, for example, is heavily influenced by Mark Fisher, a thinker who brought his complex ideas to a readership beyond the academy through accessible yet effective prose. Pinkerton’s approach also involves discussion of socio-historical contexts of the kind that academia may find less important or suitable, such as the influence of the Japanese pornography that was imported into Taiwan when Tsai moved there. These details are nuanced and inform Tsai’s film in ways which academic writing would perhaps find less fitting or relevant.

***

A year after No Flowers was published, in the bicentennial year of the arrival of settler-colonisers, Martin presented a commissioned essay edited by Scott Murray as part of the University of California Los Angeles’ spotlight on Australian cinema, titled Back of Beyond: Discovering Australian Film and Television — a rare opportunity for Australian cinephilia to make itself heard by the wider world, in particular by American film culture. Martin took the opportunity to highlight cinephiles “down under,” with a focus on lesser-known experimental and avant-garde filmmakers such as partners Corinne and Arthur Cantrill and Philip Brophy, whose Salt, Saliva, Sperm and Sweat was recently released (an homage to B-movies). These were filmmakers on the perimeters, ones who characterise Martin’s classification of a true cinephile as someone who hates their mainstream national cinema. Yet Martin discusses them to better highlight the fact that the label of a “new wave” hardly applied in this case, since unlike the French New Wave which was more entrepreneurial and hardly state subsidised in the early stages of its foundation, these Australian filmmakers remained too marginalised and isolated from one another to truly constitute a wave or movement.

Australian film criticism finds itself in a similarly tough spot today, as Australian readers tend to value a healthy diet of current affairs, politics and sports ahead of the arts, including cinema. Martin became a critic at the mainstream Melbourne-based newspaper The Age before going into exile overseas in order to pursue his career as a critic. This self-ostracisation isn’t new: in the 19th century, it was common for artists and cultured elites to return "to the motherland" (Europe, America) and learn, train, and possibly resettle. Many local artists travel overseas to try and make it there in ways unachievable in Australia, because of greater government support and respect for the arts elsewhere (filmmakers Peter Weir, Bruce Beresford and Gillian Armstrong went back and forth between England, Hollywood and Australia throughout their careers). It is a sad truth that despite being a highly respected writer around the world and relatively successful, publishing books and working as a professor, Martin remains a slightly strange and marginal figure within the Australian landscape that he arose from, wrote about and sought to improve.

In his 1988 essay, Martin directly quotes French cinephile and filmmaker Jean Luc-Godard, who writes that “viewing, discussing and writing about films already are in fact ways of making cinema.” Martin’s definition of cinephilia as an unavowed dislike of the mainstream, particularly with regards to national cinemas, goes hand in hand with Godard’s statement, for mass entertainment by definition does not encourage the use of one’s critical faculties. In encouraging a discerning engagement with cinema, cinephilia is therefore important to the ecology and existence of the art form. The Fireflies publications are testament to this attitude, publishing niche books in a landscape dominated by largely uncritical content. Concurrently, national cinema no longer defines the cinephile as rigidly as it did during the time of No Flowers’ publication. Locally, Dogmilk produce and host their own screenings of films, providing a platform for up-and-coming film creatives in Melbourne and abroad, but their focus on Indonesian cinema is also particularly noteworthy. Film screenings are hosted across Melbourne regularly, and I often find myself with my friends watching double bills of varying qualities there. These communal film-viewing experiences often involve us discussing and critiquing what we’ve seen, which leaves me to think that Kent Jones’ emphasis on marginalisation of cinema might be limiting. It is often during these screenings that I think film culture is still alive, just in a different way.