Be Scientific, Douchebag

On the last 30 years of climate change cinema

“Whenever the legitimacy of authority comes into question, Hollywood responds with disaster movies.” - Thom Andersen, Los Angeles Plays Itself

Kevin Costner drinks his own pee. This is what everybody remembers about Waterworld (1995), exhibit A in the history of Hollywood environmentalist kitsch. In the film, Costner is seen peeing in a cup before hand-pumping the liquid through some sort of futuristic filter device, and voilà: drinkable water. Rumour has it that Costner the actor is perpetually high on marijuana – on all his sets, not just while shooting Waterworld, though recurring references to smokers, dirt, and “pure hydro” in that film give the legend a particular frisson of plausibility. In Waterworld, pollution has caused global warming, which in turn has melted the ice caps, creating a planet that is literally nothing but water – save for a rumoured Dryland. In reality, were the ice caps to completely melt, the sea level would rise approximately seventy meters – enough to flood every coastal city in the world, but not to inundate the entire globe. [1] Given Los Angeles’ routine droughts and wildfires, you might think the people working in Hollywood would approach the issue with more seriousness than Kevin Costner drinking his own urine, but they only continue to double down on this stupidity in the years that follow his notorious flop. Waterworld is just the tip of a rapidly melting iceberg.

Global warming catches on as a cultural topic in the 1990s, though it’s been unfolding around us for at least a century by that point. El Niño dominates the office water cooler in 1996. Did you see Farley on Saturday Night Live the other night? “El Niño! Spanish for: The Niño!” [2] People feel the temperature rising, but most can’t fathom the implications. When audiences see Twister that same year, many don’t make the connection between what they’re watching inside the theatre and the temperature outside air-conditioned screens. Twister is pre-dot-com bubble, pre-social media. In retrospect, its depiction of technology is quaint, even wholesome: a big tin drum called Dorothy, filled with little orbs that light up as they’re sucked into the cyclone – helping their trackers better understand weather patterns and hopefully protect the public from future extreme weather. Key word: hopefully. Twister is prime ’90s eco-optimism – a cyclone fueled by an atmosphere of inevitable progress.

Gummo (1997) is the opposite. This twister is a cycle. Just as Judy Garland’s Dorothy finds herself back in her native Kansas at the end of The Wizard of Oz (1939), Tummler, Solomon, and all the other residents of Xenia, Ohio likewise wind up right where they started. Contrary to what some of Gummo’s critics and even its director Harmony Korine have said, this grimy UFO of a film does have a beginning, middle, and end – it’s just that the only visible section is its middle. It’s the bright side of the moon, the discernible part of the tornado. Its beginning and end are right behind, out of sight but still felt. Like the meteorological event, the characters of Gummo recede from the frame, and not merely in the way that all characters still exist when they’re offscreen. Korine and his director of photography Jean-Yves Escoffier actively turn away from them at times, moving for example from a couch of glue-huffers to a framed picture hanging on a wall; a young child removes the picture and roaches scurry in all directions out of a hole it was covering. Sometimes the characters exit the room and leave the camera behind, like when Tummler pays a man to have sex with his mentally-disabled sister. Other times, they narrate over warped VHS and super-8 footage. Or they never leave the frame at all, but there’s still a sense of something missing. An albino woman talks directly into the camera and says that she has webbed toes. She never shows her feet, nor does the camera glance down to confirm. To do so would go against the film’s ethic of absence: Gummo is named after the fifth Marx Brother, who was never in any of the siblings’ movies. Even as Korine devotes his project to the Gummos of America – the people who aren’t usually given much screen time and, in fairness, might not want it – his true subject is what’s lost in the storm. Tornado footage bookends the film, and it might be helpful to think of Gummo’s scattered, at times chaotic structure as narrative debris left in the wake of these cataclysmic events. In the film’s opening scene, we see VHS footage of a dead dog impaled on a TV antenna. In the penultimate shot, a boy in bunny ears holds a dead cat by the scruff. It all comes full circle.

If the destructive weather in Gummo tears through the fabric of narrative, the bizarre meteorological conditions in Magnolia (1999) mend it. Of Paul Thomas Anderson’s many left-field choices for his third feature, the boldest may be the frogs. As the film’s various narrative strands crescendo all together at once, thousands of amphibians begin to fall from the sky. Frogs splatter against the pavement, cars, billboards, bus stops, causing untold damage. This is a Biblical plague; an act of God. When the storm is over, the entire San Fernando Valley is covered with dead frogs, yet strangely, order is restored. People start to heal. Of all the movies depicting extreme weather, Magnolia may be the most hopeful – one last gasp of ’90s eco-optimism before the raging hurricane of the 21st century.

Another Biblical storm makes landfall in theatres the following summer, with a film based on a real 1991 weather event that, if the title is to be believed, was “perfect” – though meteorologists have questioned that boast. According to a 2000 article in Inside Science, “real-life experts suggest the 1991 storm may be a victim of Hollywood hype.” [3] Among these experts is University of Washington Professor of Meteorology Clifford Mass, who argues: “Bottom line: the ‘perfect’ storm was strong, but there were plenty of stronger events on record.” Must the size of past cyclones negate the perfection of the one picked by Hollywood for dramatisation? Professor Mass clearly does not mean to downplay the severity of the 1991 nor'easter. But when he compares it to the stronger winds that hit the Pacific Northwest on Columbus Day in 1962, his words uncomfortably recall the dismissive comments on climate change from so many boomers – their doubts and denial bolstered by foggy childhood memories of wearing t-shirts in December.

Still, a storm’s gotta be pretty perfect to defeat Mark Wahlberg in 2000. Only six years after his first film role, the former rapper is headlining major summer blockbusters – he is a vessel of pure Bostonian bumptiousness that no Marky Mark punchline, hate crime conviction, or 9/11 hijacker could ever capsize. Only the Perfect Storm can, and it does. His awesome star power is no match for the even more awesome force of industrial pollution, deforestation, livestock farming, fracking – not to mention commercial fishing, his character’s occupation in The Perfect Storm. This deeply corny film is a lot more candid than most media when it comes to the effects of extreme weather: neither Wahlberg nor any of his crewmates survive, in what is a highly unusual conclusion for a Hollywood summer blockbuster. You know things are bad when not even Mark Wahlberg or George Clooney make it out alive.

After Wahlberg fails to thwart the attack on September 11, 2001,[4] the disaster Hollywood blockbuster falls out of fashion. Mother Nature takes a few years off from acting, allowing another villain to seize the spotlight: the Islamic terrorist. Just as Americans do not negotiate with terrorists, we do not parlay with rising sea levels or melting ice caps, but because none of the solutions to environmental collapse involve bombing or shooting anything, audiences aren’t interested. Except for the animated children’s movie Ice Age (2002), not until 2004’s The Day After Tomorrow does a major blockbuster depict an extreme weather event. The title says it all – climate change is homework on a Friday night. Worry about it on Sunday.

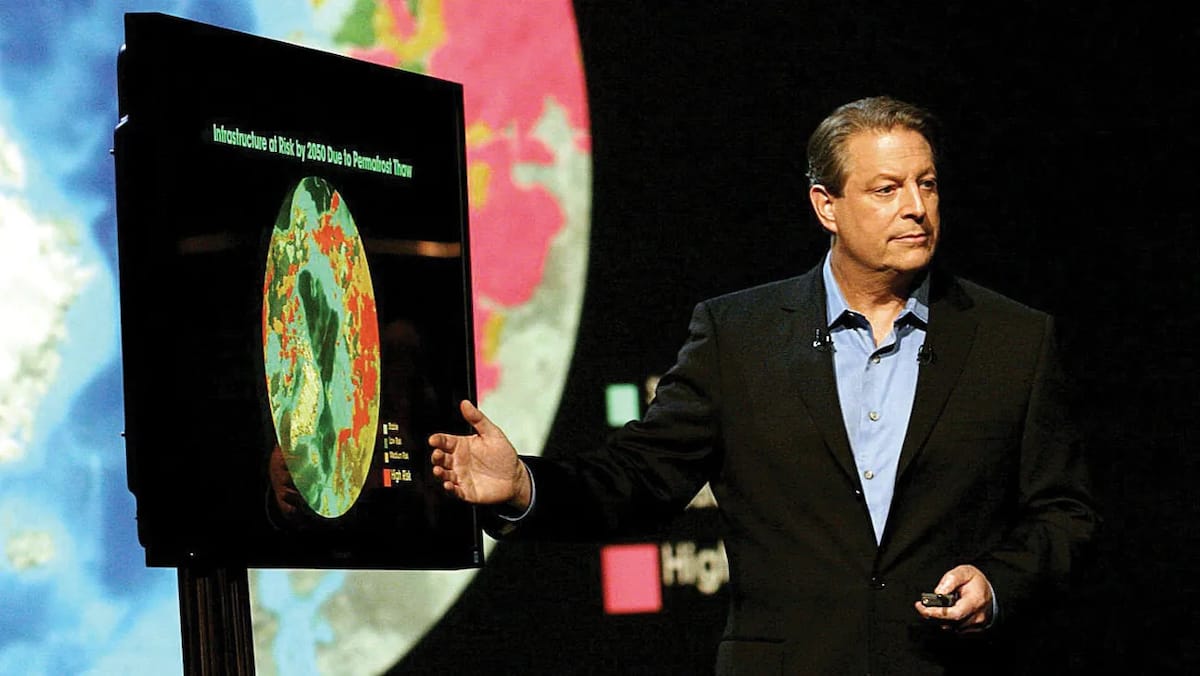

The human embodiment of homework, Al Gore stars in An Inconvenient Truth the following year. That title also says it all, though it really should be plural, since the film contains several uncomfortable facts: climate change is real and happening; the crisis has reached a tipping point and may be irreversible if not addressed in time; people created global warming and are the only ones who can reverse it; any lowering of global temperatures will require major sacrifices. Less documentary than slideshow, An Inconvenient Truth could use a more charismatic presenter, but the film makes enormous strides in educating the public about ‘climate change’, soon the favored term over ‘global warming’. Al Gore’s work towards climate justice becomes part of his persona, which he lampoons on occasion, like when he interrupts Liz Lemon on a season 2 episode of 30 Rock: “Quiet. A whale is in trouble!” [5] He returns in season 4, telling Kenneth Parcell, “Kenneth, encourage your lawmakers to take action, and recycle everything – including jokes.” When Kenneth seeks clarification, Gore interrupts again: “Quiet. A whale is in trouble!”[6]

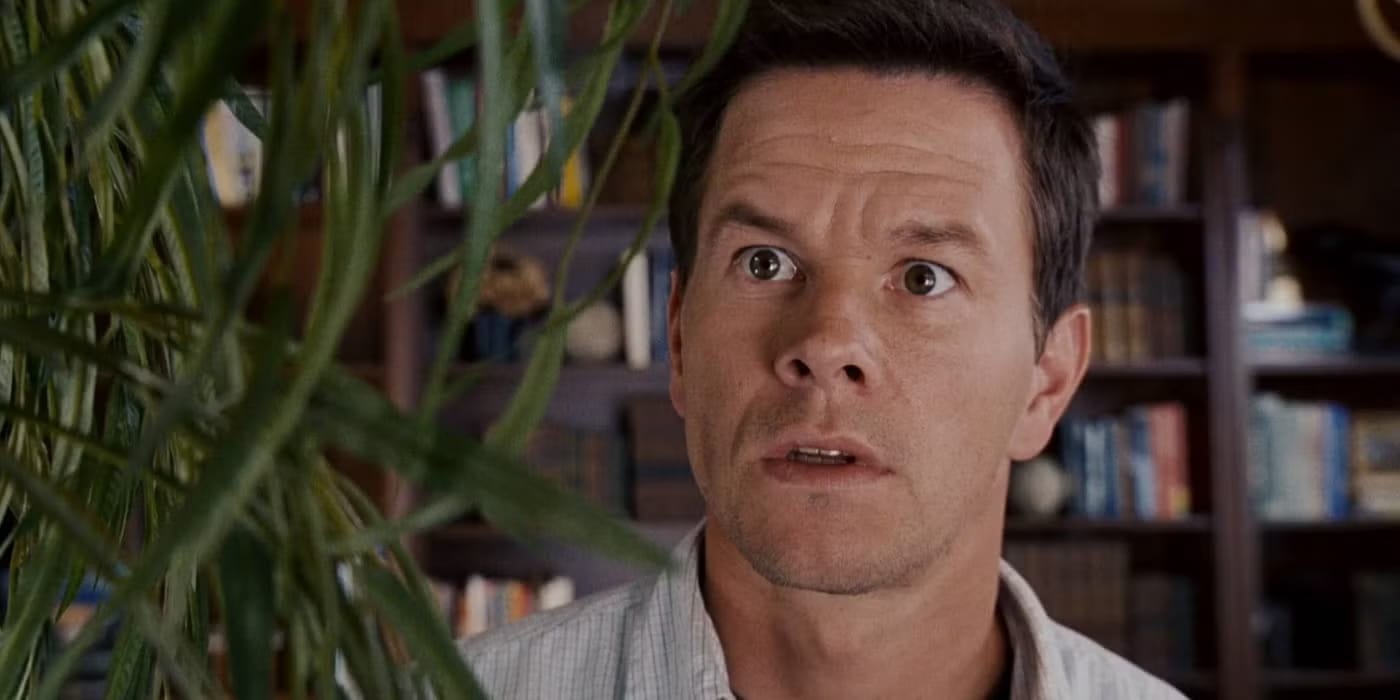

Comedy is effective at covering up bad shit. For example, the comedy of George W. Bush – the malapropisms and the ridiculous cowboy cosplay and the silly little monkey face with the ears sticking out – gives cover for his cabinet’s callous indifference towards the supposed beneficiaries of their compassionate conservatism, including the victims of Hurricane Katrina. Likewise, NBC’s National Green Week sitcom programming helps obscure its parent companies’ growing carbon footprint. The world keeps getting worse, and the only people with any power to do something about it steadfastly refuse to act in any meaningful way — now that’s comedy. M. Night Shyamalan’s The Happening (2008) tries for a different kind of humour. A film about climate change, it’s also an allegory for man’s hubris and nature’s spectacular restorative potential. Mark Wahlberg – him again – tells his high school science class, “Look, I don’t know if you’ve heard about this article in The New York Times about honeybees vanishing.” Near the end of the sentence, the pitch of his voice rises in what can only be described as the Wahlberg Lilt. What’s so funny about this scene? Is it that the meathead Wahlberg is playing a science teacher? Is it the way he rudely shuts down his students’ possible theories for the disappearance of honeybees? Or the fact that he teases the hot guy in class about the fleeting nature of his physical attractiveness, only to then tell him, “Don’t worry, you’re gonna be a heartthrob your whole life”? The funniest part of the scene might be Wahlberg’s supremely anti-scientific conclusion: “Science will come up with some reason to put in the books, but in the end it’ll be just a theory. I mean, what we fail to acknowledge is that there are forces at work beyond our understanding.” If there’s a thematic throughline in Shyamalan’s filmography, it’s the arrogance of humans – all we think we know, versus what little we do know. This dynamic is baked into his signature style: we think we know where the story is going, then Shyamalan pulls the rug out from under us with a major twist, recontextualising everything that has led up to that moment. When people start inexplicably committing suicide en masse in The Happening, possible explanations elude even super-scientist Mark Wahlberg, who chastises himself: “Be scientific, douchebag!” Wahlberg runs away in a panic from a tree bending in the breeze. He tells his travel companions to “stay ahead of the wind.” He talks to a house plant before realising that it’s plastic. At the film’s conclusion, in what might be the greatest troll in Hollywood history, the plague ends for no apparent reason. The audience is meant to conclude that nature deployed some secret evolutionary defence tactic to neutralise the threat, but no one knows definitively, and the news networks chalk it all up to another inexplicable honeybee scenario. The protagonist’s scientific agnosticism reveals an appalling lack of curiosity, but it’s not a given that Shyamalan shares his incurious perspective. When Wahlberg solicits theories from students about the honeybees, each idea offered – disease, pollution, global warming – is at least partially correct in explaining the recent decrease in bee populations. If The Happening is another Shyamalanian rebuke of human arrogance, his target is not science itself. Quite the opposite: The Happening skewers the reactionary spirit of climate change deniers, whose flat rejection of scientific theory rests on the flimsy basis that it’s “just a theory.”

One year on, the climate crisis of The Day After Tomorrow gets three years added to its deferral with 2012 (2009), which gleefully taps into a Mayan prediction for Armageddon. While the anticipated day of reckoning comes and goes without incident, the real world experiences its own series of apocalyptic visions in the meantime. Between the movie 2012 and the year 2012, an earthquake triggers massive landslides in Haiti, a six-month-long oil spill chokes the Gulf of Mexico, and a tsunami severely compromises the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan. The consequences of each disaster are felt to this day, primarily by people, animals, and entire ecosystems that had no means of preventing them from happening. In October 2012, Hurricane Sandy tears through the Caribbean and mid-Atlantic, resulting in 254 deaths. People lose their homes, pets, businesses, cars. On a televised fundraiser for the victims, Adam Sandler parodies Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” switching out its chorus with “Sandy, screw ya!” [7]

Beasts of the Southern Wild also arrives in 2012. Critics fawn over the child actor who plays the heroine; Obama loves it. The film envisions climate change as a cute adventure populated by poor Black people, even though underprivileged people of colour are most vulnerable to climate change’s least cute consequences. Has Hollywood ever produced a more offensive piece of environmentalist kitsch? Maybe The Lorax, also from 2012, which softens the alarmist ending of Dr. Seuss’ book, transforming its titular character from tragic Cassandra to superhero. With the help of a friendly middle schooler, The Lorax fights the industrialist Mayor O’Hare and brings the Truffula trees and animals back to Thneedville. The movie ends with on-screen text: “UNLESS someone like you cares a whole lot, nothing is going to get better. It’s not.” Half a century after "The Lorax" was first published, Seuss’ words feel less like a warning, more like a prophecy.

Perhaps only a director from an island nation can truly appreciate the urgency of our global crisis. Snowpiercer (2013), Bong Joon-ho’s first (primarily) English-language film, is an international production that extrapolates the current crisis with even more hyperbole than Waterworld. Frozen by a stratospheric aerosol injection, the globe is only inhabitable onboard a long, circuitous train, its compartments delineated according to social class. Snowpiercer collapses text and subtext, the central metaphor also serving as a simple statement of fact: the train is society. Occupying the caboose, the underclass is forced to eat protein bars ground from cockroaches and rodents, until the poor revolt against the wealthy front compartments. Near the end of the film, the rebel leader (Chris Evans) confronts the train architect/conductor played by Ed Harris, who tells him that the rebellion was part of a larger plot to mass-execute poor passengers and reduce the locomotive's population to sustainable levels. As if that wasn’t bad enough, Evans makes one final discovery: Harris has been forcing a kidnapped boy to serve as a missing piece of the train’s engine. Evans and his partner (the great Song Kang-ho) blow up the locomotive, killing themselves but saving the boy and Song’s daughter. A polar bear lurks not too far from the smoking rubble; the survivors’ chances of withstanding arctic temperatures, much less a bear encounter, are uncertain. But whatever happens after the crash is less important than the crash itself. The ending of Snowpiercer is an explicit homage to Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” and the film takes a comparably radical, uncompromising stance: if society is a train that can only run on exploitation, subjugation, and degradation, the train must crash.

Whether society deserves saving is a question posed to unreliable, manic father figures in 2014’s Noah and Interstellar. Russell Crowe maintains a spectacular intensity as the titular patriarch for the entirety of the overblown, insane Biblical epic – a manic energy he will channel to even greater effect for late-career paycheck roles in Unhinged (2020) and The Pope’s Exorcist (2023). The Perfect Storm might wash away a Wahlberg, but not Russell Crowe. Crowe is a beast. Noah is ready to kill his grandkids for God, but he changes his mind at the last minute. Then he gets depressed because he feels like he has failed God by disobeying him, so he gets shit-hammered on the beach. Did Noah ask himself: what would Russell Crowe do? In the months leading up to the film’s premiere, increased temperatures disrupt the North American jet stream, allowing a massive polar vortex to move southward. Less than a week before Noah is released, a mudslide in Oso, Washington kills 43 people – the deadliest landslide in US history. Director of Snohomish County's Department of Emergency Management John Pennington calls it “a completely unforeseen slide,”[8] despite years of warnings that nearby logging had compromised the hill and a 2010 report calling it one of the most dangerous hills in Snohomish County.[9] Procrastination in addressing urgent, life-threatening problems is hardly uncommon; neither is the calculus that deferring meaningful solutions to these problems is ultimately worth the fiscal and reputational consequences. Only a month later, a powerful rainstorm erodes a retaining wall in Baltimore, swallowing a block of 26th street and several parked cars into the train tracks below.[10] Residents had warned the city for months prior that the 26th street sidewalk was beginning to sag near the wall. Thankfully no one is injured, but millions of taxpayer dollars go towards rebuilding the wall. Within five years of its completion, 26th street starts to sink again.[11]

What magic number would motivate officials to preemptively address these issues? How bad does extreme weather need to get before we at least equip the earth for it? By Christopher Nolan’s calculation, people are worth saving but the earth might not be. Set in the near future, when droughts have turned the globe into a massive Dust Bowl, Interstellar concerns NASA’s mission to save the human race by sending it through a wormhole to a more inhabitable planet. Even as the movie reeks of 21st century Hollywood’s single-minded commitment to verisimilitude, Nolan doesn’t seem interested in its rigorous sci-fi framework as anything other than an elaborate set-up for a big emotional payoff – a giant, exhaustively researched, metaphysical Rube Goldberg machine with the modest goal of reuniting a father and daughter. In other words, the lamest game of Mouse Trap ever played. Since the film’s release, tech billionaires have gone all in on the idea of abandoning the globe, spending billions of dollars not to save our planet, but to give up on it and colonise space. Elon Musk’s SpaceX wants to create a sustainable colony on Mars, a project that several scientists have said is unfeasible.[12] [13] [14] Within a decade, NASA awards Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin $130 million to develop its Orbital Reef commercial space station.[15] For billionaires, the appeal is simple: Musk and Bezos get to play with rockets and, even better, stay the course in our planet’s ruination – confident in their assumption that when the world is no longer inhabitable, they can blast off and set up shop elsewhere.

Within a few years, the Trump administration all but neuters the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), pulls out of the Paris Agreement, and undoes the last twenty years or so of American environmental protections. With a ludicrous storyline featuring climate-altering satellites, Geostorm (2017) is exactly the kind of stupid that could inspire the Commander in Chief to ask his advisors if he can nuke a hurricane.[16] When Gerard Butler takes the satellite system online and stops a typhoon from hitting Shanghai, he is fired for acting without authorisation. Later, Ed Harris tries to use the satellite system as a weapon against the Democratic National Convention. (Ed Harris is always pulling shit like this. Think about it: The Rock (1996), Geostorm – okay, pretty much just those two.) Why Ed Harris wants to attack the DNC with weather is never clear, outside of the fact that the Democrats hate freedom. But Gerard Butler still manages to save the President. (Gerard Butler is always doing shit like this. Think about it: the Has Fallen series (2013-2019), Geostorm – alright, I guess just those two.) Geostorm envisions a world where the enemy isn’t climate change but those who want to weaponise the climate itself for political purposes. While the politicisation of environmental collapse is nothing new, the film grossly overestimates technology’s mastery of the elements. If nothing else, this misplaced optimism will make Geostorm an interesting artifact for more advanced alien races excavating our desiccated planet in the (near) future.

Donald Trump’s tax cuts arrive on January 1, 2018, a late Christmas present for the wealthiest Americans. By the end of the year, Hurricane Florence batters the Carolinas, wildfires destroy close to two percent of California,[17] and Trump brings in close to half a billion dollars from his various businesses.[18] (All these events – Trump tax cuts, a devastating hurricane in the Carolinas, cataclysmic wildfires in California, and Trump subverting the executive office for personal gain – will repeat themselves in 2024-25.) The ambient grift of Trump’s presidency sends the climate change blockbuster into avaricious territory: what if someone pulled off a heist during a hurricane? That’s the question driving Hurricane Heist (2018), a blunt, straightforward product of American action filmmaking. Exploiting extreme weather for profit is hardly an original idea: oil companies like Shell have tapped melting glaciers for unused oil reserves; investors buy farmland in anticipation of food and water shortages.[19] [20] Michael Burry, the weirdo finance genius played by Christian Bale in The Big Short (2015), stockpiles water shares forecasting the same.[21] By the final scene, Hurricane Heist’s crisis acceleration grindset feels indistinguishable from this kind of shameless climate change profiteering, a grim distillation of upward social mobility in the era of extreme weather: smiling and laughing, the newly wealthy heroes drive away from their hometown – where, presumably, people are still stranded on their roofs or drowning.

Floods are just a fact of life for the Kim family in Parasite (2019), who live in a tiny basement apartment that overflows anytime it rains. The clammy smell of stagnant water stubbornly clings to their skin. To make money, they assemble boxes for a local pizzeria, until the son one day gets a job tutoring a wealthy schoolgirl (his sister helps him Photoshop his credentials). Little by little, the whole gang enters the employ of this rich family, who have no idea that the new help are all related. Though the Kims’ station improves marginally, the apartment continues to flood, their employers unable – or unwilling – to conceal their disgust at the stench emanating from them. In its first act, Parasite seems headed in the direction of other films depicting domestic workers who slyly subvert the established hierarchy of the house: Joseph Losey’s The Servant (1963), or Kim Ki-young’s The Housemaid (1960). Bong Joon-ho cites the latter as an inspiration, but a second-act twist sends Parasite down a different path: the poor family one day finds, squatting in a hidden bunker underneath their rich employer’s house, the servant of the former owner. Inter-class warfare becomes intra-class warfare: in Parasite and beyond, climate change doesn’t just drive a deeper wedge between the rich and poor, it also divides the poor among themselves. Families battle over resources, or are forced to relocate for whatever opportunities arise. You take what you can get, even if that means secretly leeching off more privileged people in a hidden bunker beneath their home. It’s a living.

In the climate change economy, warning others about incoming disasters can be a living too, sometimes a lucrative one. Don’t Look Up (2021) recalls The Happening in its allegorical treatment of climate change, but unlike Shyamalan’s movie, it’s not funny. Adam McKay’s satire is at its sharpest (or least dull) when skewering the lucrative cottage industry of purely cosmetic environmentalism. The rigid scientist (an impossibly sexless Leonardo DiCaprio) is seduced and distracted by the luxurious life of big media, even as Armageddon approaches. Despite Jonah Hill’s inspired turn as the president’s foppish failson, something about the film doesn’t work, and it’s not just the fact that it’s a Netflix production, or that its star promotes environmentalist causes while regularly traveling by private jet. As in all of McKay’s post-Ferrell films, even as the director’s leftist commitments never waver, Don’t Look Up’s awards-baiting eagerness to please undermines its progressive credibility. In the same way that all war movies seem to end up glorifying conflict, it appears next to impossible to make a big-budget climate change satire that doesn’t carry a strong whiff of hypocrisy and self-congratulation.

Don’t Look Up earns four Oscar nominations, and less than a week before the ceremony that broadcasts Will Smith slapping Chris Rock live to the entire world, a huge cluster of tornadoes sweeps across the southern United States, accompanied by heavy floods. Five people die, over 68 are injured, and more than 1,300 homes are damaged.[22] These events are just a few papercuts in a series of thousands. Maybe that’s why Don’t Look Up fails so miserably: an imminent, world-ending asteroid and the protracted pain of climate change are too dissimilar for the allegory to work. In extinction theory terms, the asteroid is what’s called an ‘extrinsic catastrophe’, while climate change is ‘intrinsically gradual’. One comes from outside, the other occurs within. One is a quick death, the other is very slow. One affects everyone more or less equally, while the other is selective. McKay and company tell us what we all basically know by now – that humans ignore the climate crisis at their own peril – while missing what might be the most inconvenient truth of all, at least for the wealthy denizens of Hollywood: money largely insulates the rich from climate devastation. That’s a major reason why nothing ever gets done about it. The threat will never be as urgent for the powerful as it is for the more vulnerable residents of New Orleans, Daiichi, Steelhead Haven, Baltimore, Tornado Alley, or just about anywhere else. The finality of imminent extinction makes no meaningful impression on those who don’t believe in endings. In the land of sequels, nothing is ever final.

Twisters may be the first serious climate change blockbuster – or at least the first remotely artful one that wasn’t directed by Bong Joon-ho. The movie is atypical in a few ways, but the lack of violent action is what stands out the most: a big-budget Hollywood adventure film that features zero guns, killing, or even fist fighting. Its violence is limited to the acts of a cold, indifferent Mother Nature and those of an even colder real estate-tech alliance, which reduces the American landscape and even its skies to a series of commodifiable data points.

Daisy Edgar-Jones is the best storm tracker out there – the John Wick of storm-tracking. She’s working for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and she’s understandably hesitant to join her friend Javi on the storm trail after almost dying in a tornado in the movie’s opening sequence. Javi tells her that new lightweight 3D imaging tech allows for more detailed, accurate, and safe tracking than ever before. It could save lives. Still, she refuses. Javi hounds her with news stories about entire towns being levelled until she agrees to help for one week. Edgar-Jones doesn’t know that Javi’s company is getting its seed money from a real estate tycoon, who swoops in and offers desperate families pennies on the dollar for their land.

On the storm trail, she meets a YouTuber who calls himself a “tornado wrangler” and sells t-shirts with his face on it. He is played by Glen Powell, the new heartthrob du jour. Every woman I talk to about Powell tells me she doesn’t understand the appeal. I usually say he’s funny, or he’s charismatic, or both. They say: yeah, but… I think: what’s there to “but”? He’s got a six-pack, a jawline, he can act, he’s funny – that’s it. When I first see him, as the philosophical Finnegan in Richard Linklater’s excellent Everybody Wants Some!! (2016), I assume that anybody who can make such a sexist loudmouth of a character this likable is going places. I’m not surprised that he’s a leading man now, playing another cocksure country boy – the kind of rural character who gives the nickname New York to anyone from the city. At first, Edgar-Jones counts herself among the ranks of women who don’t get Glen Powell. The two antagonise each other before becoming friends, working together on her cloud-seeding experiments to neutralise tornadoes. After a couple of unsuccessful attempts, Edgar-Jones adds silver iodide to her seeding mixture, finally stopping a twister dead in its tracks. Her work done for the time being, she goes to the airport. Powell follows. Her flight’s delayed – heavy storms. They exchange romantic glances but no bodily fluids. On my way out of the theatre, I hear several people complain: they didn’t kiss!

That’s the big note for the producers of Twisters: more kissing. Considering all of the film’s scientific implausibility and, true to its IP, sanguine outlook on technology’s potential against climate change, you’d think it could have allowed for the less far-fetched possibility of two ridiculously attractive scientists getting caught up in the heat of the moment and engaging in some mouth-to-mouth contact. In fact, I know that the scenario was considered after a friend sends me a video of Powell and Edgar-Jones kissing in an alternate take. If there is a throughline to the past thirty years of climate change cinema, it’s the desire for fantasy – the fantasy of a world where beautiful people stop tornadoes and then kiss. A world that doesn’t suck so much.

The increase in major cyclones depicted in Twisters does suck, figuratively and literally, but it is by no means anomalous. The surge in major storms is part of a pattern of extreme weather caused by climate change. While this is not directly stated by any character in the film, it’s heavily implied by the growing size, frequency, unpredictability, and destructiveness of the tornadoes. For climate scientist Margaret Renkl, that’s not nearly enough. In her op-ed for the New York Times, she notes that the movie never once mentions global warming or climate change explicitly, an absence that constitutes a missed “opportunity to talk about what scientists know and don’t know about how climate change might be affecting the formation, strength, frequency and geographic distribution of tornadoes, or why they now tend to develop in groups.”[23] I’m not sure what Renkl believes such an overt explanation would do. In a context where raising awareness about climate change now clearly amounts to beating a dead horse, her complaint that Twisters fails to confront the topic directly enough begins to sound a lot like a familiar, patronising argument about film representation. Must Twisters make a point of openly denouncing climate change, in the same way that art depicting immoral behaviour should always, according to some, explicitly condemn that behaviour? It’s a logic that insults the audience’s intelligence more than any asinine Hollywood product ever could. Anyone who watches the clusters of F4 and F5 tornadoes portrayed in Twisters and doesn’t get that climate change is to blame – the film came out in July 2024, during the hottest summer on record to date, no less – is being wilfully obtuse. The filmmakers’ decision to spare their audience the science lesson has nothing to do with “avoiding the cross hairs of political polarity” or trying to “protect their film from the right-wing vigilantes targeting wokeness,” as Renkl claims. Rather, it’s about not getting bogged down in exposition, especially the boring scientific kind.

No one sees a movie like Twisters for the science, which I initially assume is complete junk. I’m surprised to read a Slate interview with Rick Smith, the warning coordination meteorologist at the National Weather Service Forecast Office in Norman, Oklahoma, in which he says that blasting 1,500 kg of sodium polyacrylate into a tornado to absorb its moisture, along with silver iodide to increase the cold pool and choke its fuel supply, could in theory work.[24] To Smith’s knowledge, no one’s ever tried it. I start to wonder if there might be something to Twisters’ methods of storm intervention. Could the illusion be real?

I go out for drinks with my friend Grace, who moved to Puebla, Mexico a year ago to teach English and is visiting her folks for a few weeks. We talk about Twisters, eventually arriving at the topic of cloud-seeding and the possibility of choking storms. She tells me about the Volkswagen plant in Puebla that uses hail cannons, which fire oxygen and chemicals into the atmosphere to prevent hail and protect the vast car lots, “instead of, you know, building a roof.” She says that nearby farmers brought a class action lawsuit against Volkswagen for causing draughts and ruining crops. When I read up on hail cannons later, I discover that their science is contentiously debated. Some recent data suggests they might possibly work,[25] but it’s hardly definitive. With that in mind, anyone trying to stop hailstorms – much less tornadoes – with cannons and rockets appears more than a little ridiculous. I start to see why selling such a fantasy might rankle a climate scientist as passionate as Renkl.

Even as it denies the audience its preferred romantic denouement, Twisters weaves the notion of fantasy through its text with unusual self-awareness for a Hollywood movie – climaxing in, of all places, a movie theatre. Powell and his fellow storm chasers herd people inside, telling them to stay low. Playing on the screen is James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931). While the storm batters the roof of the theatre, inside, Dr. Frankenstein screams: “It’s alive!” People move deeper down the aisle. The exit doors violently swing open and shut. Powell looks up at the ceiling and ominously notes, “This theatre wasn’t built to withstand what’s coming.” Soon enough, the roof detaches. The screen flies away, the fantasy’s over. It could only hold for so long.

Richard B. Alley et al, “Ice-sheet and sea-level changes,” Science 310, no. 5747 (2005): 456, https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1114613 ↩︎

“El Niño.” Saturday Night Live, season 23, episode 4, “Chris Farley/The Mighty Mighty Bosstones,” directed by Beth McCarthy-Miller, written by Hugh Fink, aired on October 25, 1997, on NBC, https://youtu.be/mkSRUf02gu8?si=xGiGtb7boPbjux1y. ↩︎

AIP Inside Science News Service, “Meteorologists say 'Perfect Storm' not so perfect,” ScienceDaily, June 29, 2000, www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2000/06/000628101549.htm ↩︎

Mark Memmott, “Mark Wahlberg: With Me Aboard, 9/11 Hijackers Would Have Been Stopped,” NPR, January 18, 2012, https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2012/01/18/145404733/mark-wahlberg-with-me-aboard-9-11-hijackers-would-have-been-stopped. ↩︎

30 Rock, season 2, episode 5, “Greenzo,” directed by Don Scardino, written by Jon Pollack, aired November 8, 2007, on NBC, https://www.hulu.com/watch/7b7968eb-4a95-49e1-9cde-e4f7ec833e14. ↩︎

30 Rock, season 4, episode 6, “Sun Tea,” directed by Gail Mancuso, written by Dylan Morgan and Josh Siegal, aired November 19, 2009, on NBC, https://www.hulu.com/watch/45e78791-80a5-46df-b3b6-131abb51e98d. ↩︎

Sandler, Adam, “Sandy Screw Ya,” 12-12-12: The Concert for Sandy Relief, aired Dec 12, 2012, on HBO. ↩︎

Mike Baker, Mike Carter, Ken Armstrong, “Risk of Oso landslide ‘unforeseen’? Warnings go back decades,” Seattle Times, March 24, 2014, https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/risk-of-oso-landslide-unforeseen-warnings-go-back-decades/. ↩︎

Jim Brumner, Michael Berens, “Oso landslide area was called dangerous in 2010 federal report,” Seattle Times. March 25, 2014, https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/oso-landslide-area-was-called-dangerous-in-2010-federal-report/. ↩︎

Fern Shen, Mark Reutter, “Railroad retaining wall falls down in Charles Village,” Baltimore Brew, April 30, 2014, https://www.baltimorebrew.com/2014/04/30/railroad-retaining-wall-collapses-in-charles-village/. ↩︎

Colin Campbell, Kevin Rector, Sarah Meehan, “East 26th Street in Baltimore sinking again near site of 2014 collapse — raising questions about inspections,” Baltimore Sun, June 30, 2019, https://www.baltimoresun.com/2018/11/26/east-26th-street-in-baltimore-sinking-again-near-site-of-2014-collapse-raising-questions-about-inspections/. ↩︎

Bruce Jakosky, Christopher Edwards, “Inventory of CO2 available for terraforming Mars,” Nature Astronomy 2 (2018): 634—639, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41550-018-0529-6. ↩︎

Stan Jastrzebski, “Purdue Students To Buzz Aldrin: Elon Musk's $200k Mars Plan Unfeasible,” WBAA News, April 18, 2017, https://www.wbaa.org/science-and-environment/2017-04-18/purdue-students-to-buzz-aldrin-elon-musks-200k-mars-plan-unfeasible. ↩︎

Tim Fernholz, “NASA says nobody—not even Elon Musk—can terraform Mars,” Quartz, August 1, 2018, https://qz.com/1345912/nasa-says-nobody-not-even-elon-musk-can-terraform-mars. ↩︎

National Aeronautics and Space Administration, “NASA Selects Companies to Develop Commercial Destinations in Space,” December 2, 2021. https://www.nasa.gov/news-release/nasa-selects-companies-to-develop-commercial-destinations-in-space/. ↩︎

“Trump suggests 'nuking hurricanes' to stop them hitting America – report,” The Guardian, August 26, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/aug/26/donald-trump-suggests-nuking-hurricanes-to-stop-them-hitting-america-report. ↩︎

California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. “2018 Incident Archive.” https://www.fire.ca.gov/incidents/2018. ↩︎

Anna Bahney, Maegan Vazquez, “Trump reports making at least $434 million in 2018.” CNN, May 16, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/05/16/politics/donald-trump-financial-disclosure/index.html. ↩︎

Ted Williams, “Shell Shows It Can’t Ensure Safe Offshore Oil Operations in the Arctic,” Audubon Magazine, December 6, 2013, https://www.audubon.org/magazine/shell-shows-it-cant-ensure-safe-offshore-oil-operations-arctic. ↩︎

Leah Douglas, “Investment funds stocking up on US farmland in safe-haven bet,” Reuters, November 16, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/investment-funds-stocking-up-us-farmland-safe-haven-bet-2023-11-16/. ↩︎

Jessica Pressler, “Michael Burry, Real-Life Market Genius From The Big Short, Thinks Another Financial Crisis Is Looming,” New York Magazine, December 28, 2015, https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2015/12/big-short-genius-says-another-crisis-is-coming.html. ↩︎

Jan Wesner Childs, “Five Dead, More than 1,300 Homes Damaged in Tornadoes, Flooding Across the South,” Weather Channel, March 25, 2022, https://weather.com/news/news/2022-03-24-south-tornado-outbreak-storms. ↩︎

Margaret Renkl, “‘Twisters’ Was a Spectacle That Missed a Huge Opportunity,” New York Times, July 31, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/07/29/opinion/twisters-failed-climate-change.html. ↩︎

Nadira Goffe, “Could You Really Stop a Tornado by Shooting It With Rockets, Like in Twisters?,” Slate, July 20, 2024, https://slate.com/culture/2024/07/twisters-movie-glen-powell-scientific-accuracy-diaper-gel.html. ↩︎

Krzysztof Misan et al., “The First Scientific Evidence for the Hail Cannon,” Computational Science — ICCS 2023, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 14073, https://www.iccs-meeting.org/archive/iccs2023/papers/140730185.pdf. ↩︎