Begotten

E. Elias Merhige’s cult classic makes us look between the frames

People who worry about the distinction between the life lived and the life examined need to check out that thing called cinema. Watching a film always involves a degree of push-pull between watching the screen, and being afraid of it. Between simply seeing the image, experiencing it, letting it affect us in whatever way it might; and thinking, anticipating, trying to predict the image. For certain filmmakers like Gaspar Noé, this dynamic is at the very heart of what they do: his films can offer the pleasure of vision, as the viewer abandons themselves to the screen (the blissed-out sections of Enter the Void, the choreographed moments of synchronicity in Climax), but also the horror of seeing too much, or too little (Irreversible, Vortex). As the viewer moves from anticipation to overwhelm and vice versa, Noé plays with the illusion of control that cinema can provide, bringing to the fore our inability to escape not just from the image, but from experience — from life itself.

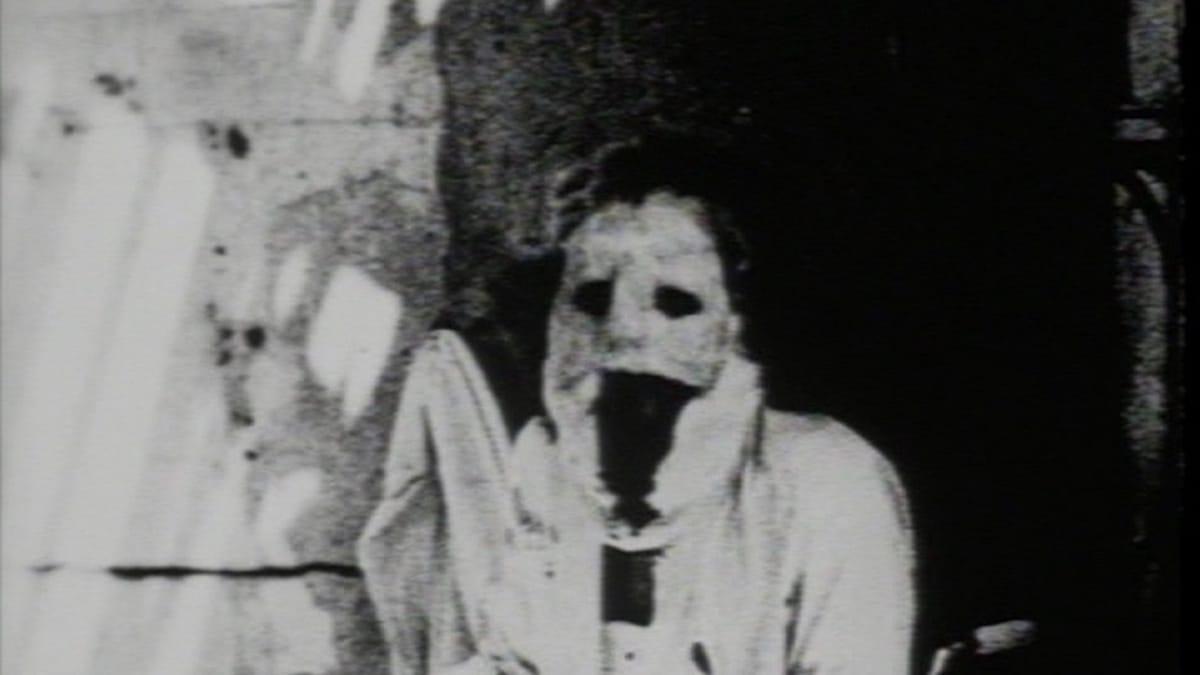

With that in mind, it isn’t surprising that horror would be best suited to this kind of liminal experience, and E. Elias Merhige’s Begotten (1989) contains many horrific images, within its horrific story of birth and destruction. However, the film does not employ jump scares, or other more conventional tropes of the genre, to make the viewer oscillate between curiosity and revulsion. It instead borrows techniques more familiar from experimental cinema: shooting on black-and-white film and using a variety of techniques to alter the surface of the celluloid, Merhige intentionally obscures the boundaries between the objects and people captured, collapses all dimensions, over- or under-exposes the frames, until the image is almost completely reduced to an abstract combination of shapes. “Almost” is key: in the blink of an eye, at the turn of a frame, suddenly one can make out a figure; on closer look, they appear to be hacking off a piece of their own body, or carrying strange trinkets, or writhing in pain on the ground. In a sense, Begotten does feature jump scares, but they are within the images themselves, in between the frames, in the gap between the seen and the unseen.

Ten years after Begotten, Eduardo Sánchez and Daniel Myrick’s The Blair Witch Project would launch in earnest an era of horror cinema that mined the uncertainty in digital video’s blurry pixels. In 2022, Kyle Edward Ball’s Skinamarink similarly used the haziness of low-res video, ubiquitous on the internet, to make us squint in fear at the darkness. But Begotten does not rely on our familiarity with grainy images — the way they can recall amateur footage, or even our own home videos from childhood — to touch on something recognisable and primal. Its play with images, with black and white, with darkness and light, harks back to the mechanism of cinema itself.

“At 24 frames per second,” Merhige wrote in a piece for movieScope magazine in 2008, “the motion picture projector alternates between light and dark. An image is seen, followed by darkness where it persists and gives birth to the next image seen. The brain, the mind, the part that sees when we dream in deep sleep is the part that makes the illusion of vision possible. The Zoetrope is a perfect example of this extraordinary phenomena of what is known as the ‘Persistence of Vision.’”

The strobe light sequences in Noé’s films bring that phenomenon to the fore like few others; as a white light flashes in between his images, the latter appear to break down, and the effect is undeniably trippy. But for Noé as for Merhige, revealing the flickering nature of cinema isn’t a gimmick.

“I found it essential to create a hypnotic ‘flicker’ state on one pass of the film and then run it back to the beginning and expose an overlay of previously shot image over that,” Merhige writes in the same piece. “This gave the image further access to that deeper most ancient part of the viewer’s brain: the Arbor Vitae, the part of us that assembles the world by giving it motion and continuity.”

Indeed, the breaking down of the image for Merhige isn’t just about the illusion of continuity in cinema — more than assembling images, it assembles the world. For Merhige, that principle of flicker — the idea that things appear and disappear constantly but too quickly for us to notice — applies also outside of the screening room:

“In physics, light wave/particle theory tells us that everything from a stone to the human body, to our very Earth is made up of electrons/atomic matter that pulse in and out of appearance, making the world itself an illusory projection.”

The gap between the seen and the unseen, the difference between one frame and the other, is for Merhige the source of the great mystery of existence, and the force that moves Begotten forward. How can something exist, then no longer exist? Who makes these kinds of decisions? In Noé’s work, drawing attention to vision’s flicker — whether through strobe light sequences, split screens, or the image regularly going black as though the camera was blinking — reveals a deeper, previously unseen pulsating rhythm beneath the everyday, the billions of lightning-fast processes that take place right in front of our eyes but that we simply cannot see. Those invisible processes are change; implied in change are death, birth — creation. As Merhige writes, “Everything we look at is a zoetrope, a series of ‘stills’ set into motion by an ancient part of our brain, what I call the First Projector. This means that for an infinite fraction of a nano-second the space the earth fills as it speeds around the sun is empty and void of being. Where does it go? What is in the brief emptiness for us to see?”

That so much of Noé’s cinema is concerned with birth and death, drugs and (subjective) perspective, makes perfect sense — all have to do with the very stuff of living, and how much of it we can really understand. Merhige’s Begotten makes these concerns explicit by employing a narrative of birth, death, and rebirth cut off from recognisable daily life, steeped in the world of myths and dealing directly with the elements.

At the beginning of the film, a creature wearing a mask reminiscent of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’s Leatherface is seen sitting in a chair, inside a dilapidated house isolated among the trees. This is as close to mundane, everyday reality as we’re going to get — the rest of Begotten takes place in nature, made to look through Merhige’s manipulation of the image about as hospitable as the surface of the moon. The film does not appear to be taking place in our world, and from the start, Merhige plays with image resolution and a busy soundscape of mysterious, scrappy sounds to create the feeling of witnessing something both impossibly alien and unbearably close. Although a house is a reassuringly banal setting, it is impossible to find refuge in it from the film’s absorbing strangeness for long. Even as we watch the male masked figure shaking, spitting blood, and cutting his own stomach open with a blade, the thought that “this is just an actor, there are cameras, it’s only a movie” doesn’t help. After the man finally lies still in his chair, with blood spilling down his foot, a female figure emerges from behind him; she soon begins to masturbate him, then smears his ejaculate over her body and into the folds of her sex.

What is happening? Clearly it has something to do with death and birth, and the chaos of creation, but we are hardly given any clear answers as the film moves along. A creature is born: a young man covered in mud, squirming on the ground, its limbs shaking uncontrollably. It is almost certainly in pain from the moment of its birth. A group of cloaked figures carry it across a desolate landscape; they seem to take care of the creature, in their clumsy and lumbering way, but also regularly interrupt their journey to torture or mutilate it. Its mother, too, is the subject of their apparently ritualistic, automatic violence. Genitals are mutilated. Organs and flesh are feasted on, or ground into a paste. Until, finally, nature and greenery take over, plants sprouting up while mother and son, now dead, lay in the dirt.

Merhige’s refusal to provide any explanations, as well as the slow but steady way in which the strange ritual and the film itself progress, make Begotten a film that demands to be approached the way one would an artefact, a standalone object. Although there is a degree of narrative and straightforward interpretation involved, this is not where the film’s real core lies. Writes Merhige:

“It is important to mention here that Begotten’s narrative is a story not meant to be assembled from what one sees on the screen. What you actually see with your eyes and conscious mind is unimportant — this is meant only to serve as a map and a door toward a point of origin made aware of its own existence through the experience of watching this film.”

What of ourselves can be revealed when a film encourages a different way of engaging with it? Beyond the apprehension and curiosity that its horror-adjacent images evoke, Begotten also offers a kind of experience well beyond the alternating modes of passivity and control that cinema often plays with. Is it a hyper-embodied type of awareness, where the infinitesimally small and the exponentially large inside all things is suddenly made visible? Or a completely disembodied position, destroying the illusion of anything constant and unchanging, revealing unstoppable decay and creation, placing the viewer at one with the elements? Probably both, as we flicker in and out of existence.