On Film Criticism #1: Why write?

The first part in a series on what exactly we are trying to do here

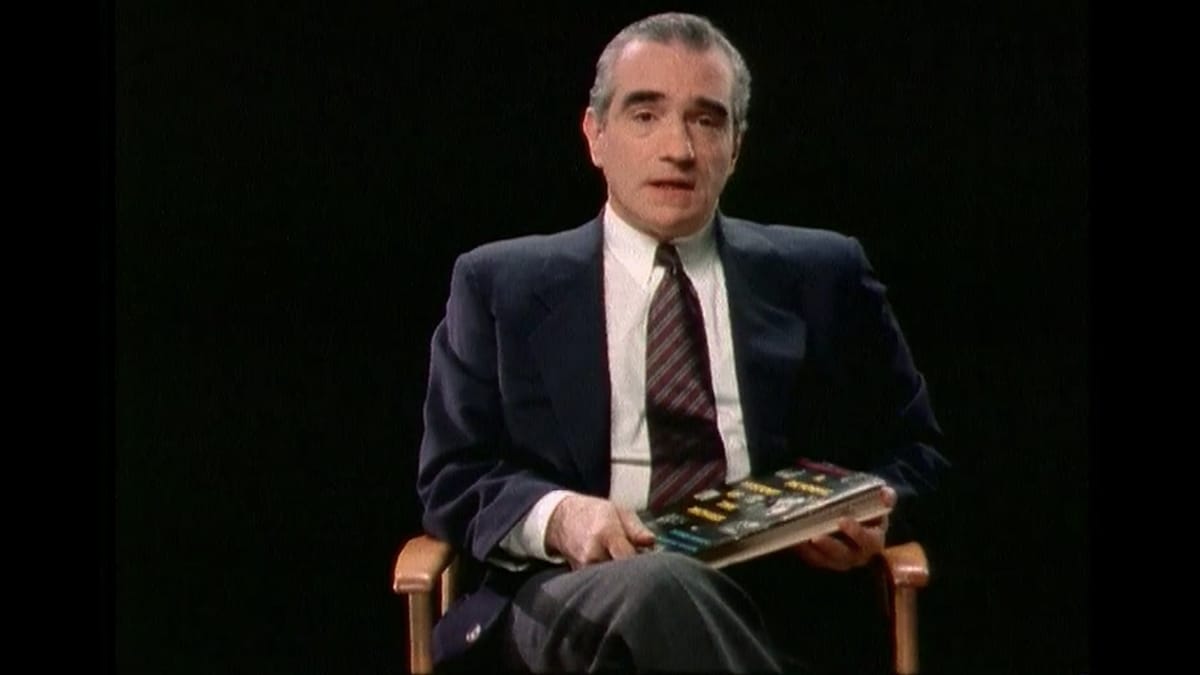

Early in A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies, the director talks about his childhood as a film-obsessed youth and the big book about movies that he liked to peruse at length whenever he was not in a cinema. The glimpses we get of pages from “A Pictorial History of the Movies” in the documentary show a kind of encyclopedia which, while definitely pictorial, features quite a lot more text than the books most children are understood to favour. The films mentioned are illustrated with just a still or two, and the writing seems rather dry. Yet in Scorsese’s own words, the book “cast a spell” on him. He explains that the black-and-white stills were often the only way he could “experience” some of the films mentioned, that he would “fantasise” about those images, that they would “play into [his] dreams.”

This might strike one as no more than a charming image of youthful obsession, an example of the kind of one-track-mind that over-excited children often have, young “Marty” obsessed with movies the way others might be with fire trucks or Peppa Pig. But looking beyond the cuteness, this anecdote also reveals a relationship to cinema in general and to film writing in particular that is premised on curiosity and imagination. To Scorsese, it almost didn’t matter that he could not see some of these films — he wasn’t going to stop thinking and dreaming about them simply because he would not have the opportunity to see the actual, finished product. Starting from the text and pictures on the page, his mind found its own way of connecting the dots and filling in the blanks. The act of imagining what other images and sounds he was missing was thrilling in itself.

Today, encountering a text about or a still from a film without being able to easily find the actual film online is a rare experience for most people, children included. The gap between the incomplete fragments of a movie and the actual movie itself, which brought Scorsese so much joy, appears to have closed. Erika Balsom writes about this beautifully in the third chapter (available online) of her book on James Benning’s Ten Skies, and she wisely connects this phenomenon to the emergence of video essays. She discusses the way in which having extracts from a film right in front of one’s eyes while the video essayist or critic makes their argument about that film “[banishes] the mental image summoned by language in favour of the actual image.” With films readily available to us, it seems we are less encouraged or inclined to imagine them. Would baby Marty have been haunted by an obscure movie from the 1940s if he had been able to source a copy of it in five minutes? Would he have cared to read about it at all?

No one is arguing for a return to the times when watching movies was this complicated. And after all, it wasn’t really his inability to see films that triggered Scorsese’s imagination — it was the book, the still images together with the words. Even as a child, the director-to-be recognised the power of words and the excitement in picturing, in his mind’s eye, what they might be referring to.

Later in her chapter, Balsom writes about a similar kind of “delight” in reading film criticism that brings out aspects of a film which wouldn’t naturally stand out, for these to be enjoyed on their own or because they reveal the essential core of the film particularly well. In making the reader look at a specific film from a different angle, this kind of writing naturally engages a reader’s imagination — their ability to imagine. The reader gets to see, in their mind, something new that they had not themselves seen in the film, and that alone is delightful.

But Balsom also writes about how most writing, consciously or not, does this. Just as it is impossible to give with words a precise description of a cloud from Benning’s film (even the scientific names given to those formations fail to attest for their individual details), so it is impossible to write a description of a film that would conjure up in the reader’s mind the exact reality of that film. There is always something missing.

Some may ask: how could four-year-old Marty stand this? The incompleteness of the text and the black-and-white images that were so far removed from the brilliant technicolor of King Vidor’s Duel in the Sun would make more than a few self-described cinephiles of today completely furious.

But Scorsese was not a cinephile in that sense. Listening to him talk, it becomes obvious that he was, and still is, obsessed not so much with films as he is with cinema, with the possibilities of a still very young art form.

This perspective on cinema based on curiosity and excitement at the very possibilities of the form leeks into the way he appreciates films themselves.

As opposed to the image of Scorsese that some would like to perpetuate, of a dusty old man whose complaints about superhero movies are only rooted in nostalgia for a time when he was the king of the box office, A Personal Journey does not show him as a cinephile who adores every single old movie he has decided to talk about. Rather, of the films he has chosen, he only discusses the aspects that have marked him, even though the films themselves as a whole sometimes did not. He describes Duel in the Sun as “flawed,” with an important caveat: “the hallucinatory quality of the imagery has never weakened for me over the years.” That film was not, in his eyes, a masterpiece, yet Scorsese got something from it which he has held onto long after the credits rolled, and which is more valuable to him than the overall quality of the film itself.

This kind of appreciation is miles removed from an exacting version of cinephilia (and a kind of criticism) which seeks to assess films only ever as finished products in and of themselves, closed off to interpretation, flattened into smooth shapes rid of any and all irregularities that might distract, confuse, or — god forbid — titillate the imagination of the viewer. That cinephilia is the cinephilia of the consensus, of Rotten Tomatoes, of the blockbusters which choose to repeat a verified formula rather than engage in any search for innovation, of the Disney live-action remakes that Disney fans watch not to be surprised, but to verify that the new film does not depart from the version from their childhood.

If Hollywood continues to churn out blockbusters and endless variations on IP, making it harder in the process for independent and national cinemas the world over to survive, perhaps one way to defend and revive curiosity and excitement for the possibilities of cinema is through words – through a kind of film criticism that looks at cinema not as content, or at films as entries in a watchlist to tick off or objects to rank. The gap between the images summoned by words and the actual images from a film could be a place where cinephiles could still be called on to use their imagination.

This type of creative criticism, which looks at films and beyond them to imagine the cinema of tomorrow, isn’t just delightful to read, as Balsom writes. It is also a way to keep cinema alive.