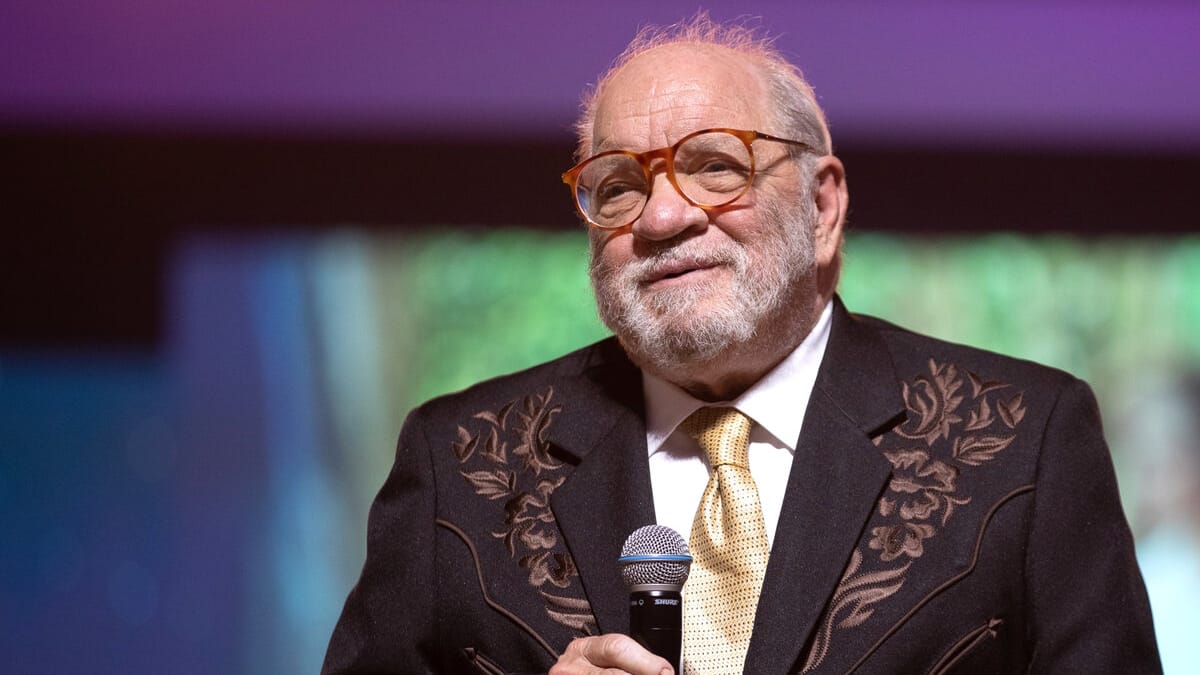

Paul Schrader’s Contradictions

American director Paul Schrader on his film Master Gardener, controversy, Facebook, Taxi Driver and more

Marrakesh was one of the locations for Dominion: Prequel to the Exorcist — “not a film I should have made,” according to Paul Schrader, who was back in town for the Marrakech Film Festival to accompany a film he seems much more happy with. Master Gardener stars Joel Edgerton as Narvel Roth, a man with a green thumb and a terrible secret. He has been working for years on the estate of a domineering woman, Norma Haverhill (Sigourney Weaver), but his life changes when her troubled great-niece Maya (Quintessa Swindell), who is Black, becomes his apprentice. I got to talk to Schrader during a roundtable interview at the festival; I have transcribed his answers to my questions in full here, and paraphrased the rest.

The eponymous Master Gardener has done terrible, heinous things in the past, but appears in the film to have turned his life around — which, as one of the journalists present pointed out, is not a redemption arc many people care to engage with. Schrader said this was a valid point, and that several people — including Toronto International Film Festival CEO Cameron Bailey — had told him they just did not believe that such a person could be redeemed. Schrader, however, claims he does not regard the film as a “realistic story” but rather as a fable, a hypothetical and “a wonderful what-if” like a Flannery O'Connor story, “something to invigorate your imagination.”

It’s the kind of apparently flippant response that people familiar with the director’s work (and Facebook posts) know to take with a grain of salt, and Schrader would go on to contradict this devil-may-care attitude several times throughout the interview. The fact that the film was shot in a botanical garden which used to be a plantation, for example, was a coincidence. Initially set for Melbourne, the shoot had to be moved to the US when Australia entered into strict lockdowns. Additionally, Edgerton’s schedule meant that the only possible time to film was March, and the place with the best climate for gardening at that time of year was, of course, Louisiana. The pandemic could have been used as a strong excuse for not only shooting, but also setting the film in a plantation; Schrader however explained that he went out of his way to take out all of the Southern-ness of the location. Beyond staying away from Southern stereotypes and accents, the decision also extended to set design, notably in the choice of the stunning blue jellyfish wallpaper that adorns one of the rooms in Norma’s luxurious house.

When discussing the details of the relationships between Narvel, Norma and Maya, Schrader however once again came dangerously close to being glib. Asked about the way his film plays with racist dynamics and stereotypes, reversing them and turning them on their heads, the director gleefully remarked that he “[loves] doing those kinds of flips.” Then, in something of a doubling down on his own irreverence: “I realised that if you get enough hot buttons on the console at the same time, nobody can focus on one of them.”

Eager to get more clarity on this point, I asked if the idea was to cause controversy, or to confuse people so as to avoid controversy. His answer was at first reassuring: the goal was to prevent audiences from getting an easy handle on the film, so that it could not be reduced to one thing and could exist as a character study. But he soon returned to his cheeky, slightly provocative ways when he mentioned a suggestion he’d jokingly made to his producer: that if they really wanted to keep people from typing the film, they could cast Kevin Spacey, then this would be all people would talk about. It was a joke, of course — Schrader knows that nothing could sink a film quicker than that — and not one made in the best of tastes. But most frustrating was that it took us away from a real discussion of the provocative instincts seen in many of his films. So I pressed on.

Elena Lazic (EL): Is this a strategy you've developed because of the way people deal with films today?

Paul Schrader (PS): I started a long time ago, with the first script. With Taxi Driver. It had this idea of the occupational metaphor. I like these metaphors that can be interpreted in more than one way. 50 years ago, when people thought of a taxi driver, they thought of some wisecracking guy, your brother in law, you know — a good natured guy. And I looked at taxi drivers and I said, this is the black heart of Dostoyevsky. This man is trapped in this iron box all alone, seething with existential anger. That's what a taxi driver really is. You find an occupation people think they know, and say it is something else — whether you have a professional card player who is in fact a torturer, etc.

These metaphors and all their adjacent what-ifs can often, in Schrader’s films, lead to several possible endings, all of them logical but each with wildly different ramifications. Master Gardener’s conclusion echoes that of First Reformed in that, even though it is less ambiguous, it can be read several ways, each with its own contrasting moral implications. I asked Schrader how and when he decides on which note to end his films:

PS: Well, as you can tell, I'm getting older, and I thought of this film as the end of a trilogy. I hadn't thought of it when I was writing, when somebody said to me, “You know, this is really the third.” I said, “No, it's not.” Then later I said, “No, you're right, it is.” And so in the first one, the character dies. In the second one, the character goes to jail. And I thought, well, maybe this time… A friend of mine, Dev Hynes, had written a song that had this wonderful lyric, “I never want to leave this world without saying I love you.” That's how the film ends, with that lyric. When I was younger, I used to believe that “I never want to leave this world without saying fuck you.” And now, I never want to leave this world without saying I love you!

There is part of the truth there: the film does end with ‘I love you,’ but also with ‘fuck you.’ Although Schrader’s answer might suggest otherwise, the film’s nuanced and profound conclusion feels like a very deliberate statement, not a flip of a coin.

For a filmmaker so active on Facebook — posting updates is his way of still being a reviewer of sorts, and his friends’ recommendations help him “see through the weeds” of all this product — it is still when given the time and space to expand on his ideas that he comes across the best. He gave a long and fascinating answer to a journalist who asked him about Quentin Tarantino’s opinion, formulated in his book Cinema Speculation, that making the character ultimately played by Harvey Keitel in Taxi Driver white was a “societal compromise.” Schrader explained that he had initially written the character, a pimp, as Black because he had simply never heard of a white pimp working at that level. It was the film’s producers who made him change the character’s race, because they were worried that ending the film with the main character killing Black people could create dangerous situations in screenings. Keitel was cast in the role, and when he asked Schrader what the character should be like, the screenwriter replied that he had no idea. So Schrader walked the streets of New York looking for “the great white pimp,” and not finding him. All was not in vain, however, since it was during that search that he met in a bar the young addict who would inspire the character of the underage sex worker played by Jodie Foster: “Now, I had just made this girl up, and here I was talking to her. Wow.” The collection of sunglasses, the piece of bread covered in sugar — these were all details taken from this young girl, called Garth, who appears in one scene walking next to Foster but was too unreliable to have a bigger role in the film.

What could have been a button-pushing answer thus turned out to be a detailed and nuanced glimpse into the creative process, as it is impacted both by active decisions and pure chance. I asked Schrader about the role of control and chaos in his films, which often feature male heroes trying extremely hard to keep a grasp on everything around them, often with disastrous consequences. Schrader, however, tied this to the idea of waiting:

PS: It started with Taxi Driver, and Travis writes, “The days go by, every day like the last day. And then there is a change.” These guys are waiting for something. They're in a kind of limbo, or purgatory. They're in their rooms, waiting. In The Card Counter, Tiffany Haddish says to Oscar Isaac, “if you're not interested in getting rich, why do you play cards?” He says, “to pass the time.” I'm waiting, you know. And what are you waiting for? He's waiting for something to happen, that will take him out of this limbo, which happens when the boy shows up. For the minister in First Reformed, it happens again, when the boy shows up, and doesn't want his wife to have a child. And here it happens when the girl shows up and needs help. The Master Gardener says, “the moment I had been waiting for had come.” And the very first thing he says in the film is, “gardening is a belief in the future,” a belief that things will happen in their due course. If you just wait, things will happen.

As eager as he seems to provoke, then — and as the process of this very interview further proved — Schrader is also a man concerned with the idea that good things take time. Asked about the reception of his films, he mentioned that he was fine with getting career awards rather than yearly awards because he finds value in the idea of films having a long shelf life. People still talk about Taxi Driver fifty years on, and Cat People — a film he finds as personal as the others, even though he did not write it — was not particularly well received in its time but has been reappraised since. Building a body of work is gratifying but, again, “before long I’ll be dead, and it won’t matter.” About his friend Martin Scorsese’s passion for film preservation: “I said to Marty a while back, why are you trying to preserve these films when we can't preserve the people who watch them?”

Speaking of legacy, Schrader explained that he already was against the idea of developing another American Gigolo ten years ago, when Jerry Bruckheimer asked him. When the idea was brought up again recently, he was not asked: the TV series would be developed with or without his consent — he did not own the rights — and his choice was between getting nothing, or getting $50,000, given to him “out of a sense of obligation.” He still has not watched the new show starring Jon Bernthal.

As evidenced by his Facebook posts, Schrader likes to keep up with recent cinema: during the Marrakech Film Festival, he posted praise about Tarik Saleh’s competition entry Boy from Heaven, also mentioning the director’s previous film The Nile Hilton Incident. A journalist also mentioned his fondness for John Krasinski’s A Quiet Place and A Quiet Place 2. He can talk in great detail about the distinction between cinema as audiovisual entertainment that can also be enjoyed at home, and cinema as the theatrical experience, which is being marginalised. He sees the strip mall and the multiplex being replaced by smaller, trendier cinemas and clubs, citing Metrograph in New York as an example.

Of his place in that changing ecosystem, he explains that he recently asked Noah Baumbach, who worked with Netflix on White Noise — a film Schrader believes “should have never been made” — when was the last time he was worried about having enough money to finish a film. For Schrader, this anxiety has become a part of the process, and he is used to the rhythm and discipline it imposes. Most importantly, he is not convinced that the “big toys” are necessary, not just for the kind of films he makes, but also for a certain kind of quality.

There were two other projects he was ready to work on. The first fell apart: it was to be a Western titled Nine Men From Now, inspired by the Budd Boetticher film Seven Men from Now which stars Randolph Scott as “an iconographic hero, a man who refers to himself in the third person.” The other script Schrader wrote, he recently sent to production companies run by women and specialised in female-centric films, because he does not feel comfortable directing it himself — a kind of self-awareness that his detractors would not expected from him. Centred on a trauma nurse in Puerto Rico, it is “about female sexuality, repression, displacement, anger,” characteristics that he admits to know in men, but not in women. As he put it, “I'm in Spike Lee's house, and I'm trying to tell them how to redecorate. I’m in the wrong part of town!” He explains that although they centred on female characters, Cat People was all about the male gaze, and Patty Hearst about being oppressed; this script is about a woman who gets in trouble because she can't control her sexual urges. “I sent it to Kristen Stewart, and she said, ‘Oh, you know, I'd love to see this movie. I don't know whether I’d want to be in it.’”

Schrader, then, comes across as a filmmaker who has always sought creative tension and a thorny, sometimes uncomfortable truth, of the kind that can only be found by wrestling with apparent contradictions. That he also enjoys pushing people’s buttons might just be a perk of the job.