Psycho. #48

God's lonely protagonist.

I've been thinking about the many great films that have rather isolated or lonely protagonists. What is it about cinema that feels so unique and special in exploring those characters?

Also, little shout out to obscure Aussie film Man Of Flowers which inspired my question (feel free to not include this part)

I wonder what films you mean! I guess that’s the weakness of this column–perhaps also its strength–in that I will possibly never know what you had in mind when you asked this question. I’m reminded of when my first child used to cry sometimes, when he was a baby. “Why is he crying,” I would ask, “is he hungry? Is he cold?!! Is he, for some incomprehensible reason, melancholy??” And one of my co-parents would shrug and say, “We will simply never, ever know.”

Send your questions anonymously to Caspar at this link, no personal information is collected.

You however are a bit different from my bawling 8-month-old with a sore bum/a great thirst/a terrible gnawing sadness at the parlous state of the world, as you might get in touch; failing that I will have to do my job and hazard a guess, using my knowledge of films and shit. At any rate, thank you for recommending Man of Flowers (Paul Cox, 1983), which I confess I had not even heard of. I see on Wiki that it’s about a man “who enjoys the beauty of art, flowers, music and watching pretty women undress” — I mean, swap women for men and I’m absolutely on board, can’t say fairer than that. I’m sorry, who doesn’t enjoy those things? Some absolute planks on the web who collect bitcoin, that’s who. I wonder who’s lonelier out of them and this fella who’s fixed up for posies and nudity, and I think I know who.

I’ll get to the films in a bit. The idea of isolated or lonely protagonists brought to mind what we’re invited to call “the current conversation around [it’s always a conversation around, never a conversation about] male loneliness.” Men are struggling to connect with women and with each other, we are told — they struggle to build friendships with each other; they feel increasingly isolated and vulnerable and find it hard to balance that with a world that tells them to be strong and spurn emotionality. The implication that men from ‘before’ did not have these problems because they were more attuned to their natural masculine essence and were allowed to brawl and fuck as they pleased, is hard to miss. The men discussed are always straight of course: the word ‘men’ is generally understood to designate heterosexuals, because homos and bisexual men represent a kind of straying from the path of masculinity.

I don’t want to dismiss any of this — clearly we’re in the midst of a big crisis in masculinity — and yet it’s possible to overstate its reach, or to misdirect one’s sympathies. Yes, men feel isolated — but so do women. We’re in the midst of an epidemic of loneliness, that much seems clear, but who’s to say that women and non-binary people aren’t also feeling it? The internet isolates us all, reinforcing our sense that we exist independently of one another and are in some ways disconnected; we are au fait with each other’s movements via the web, but miss touch, spontaneity, communion. Earlier today I saw somebody talking about the future death of Donald Trump and bemoaning the celebrations that would take place online, and all I could think was: can’t we celebrate his death all together? What of the huge parties, and making out with strangers in our joy and gaiety at his passing? The closing of bars and clubs, our servitude to our phones and technology, the ‘cost-of-living crisis’ — all of this pushes more and more of us into a dispiriting loneliness whatever our gender. Masculinity being completely fucked is a discrete issue.

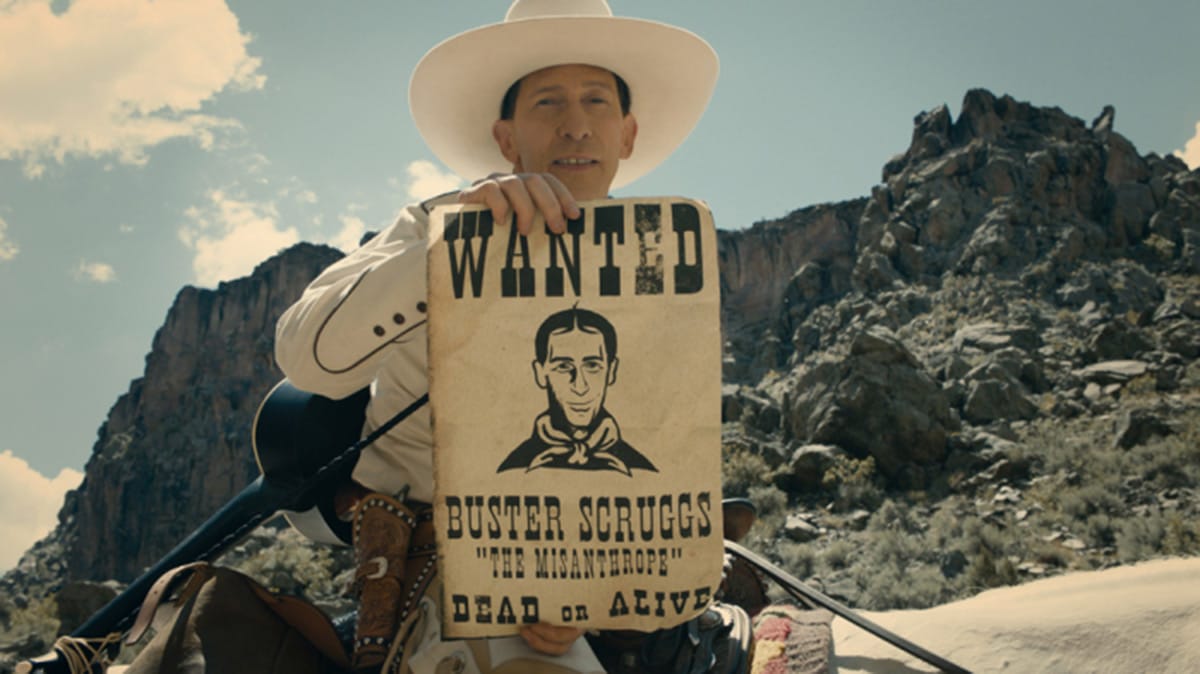

And yet the first few films that I thought of when I was considering your question were all focused on this, on the idea of a lonely man, somebody at odds with his universe who, perhaps, takes off on his own, walking a dusty high road. I’m reminded of the Coen Brothers’ pisstake of that archetype in The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018), in the form of the cowboy known as “Surly Joe”, about whom a song is sung featuring perhaps the best lyric of all time:

Surly Joe, Surly Joe

A cedilla on the c of Curly Joe

God, it really doesn’t get better than that. How wonderful. Of course, Western films rehearse this theme more than most genres, and it would be right to associate that type, the loner, with, say, Clint Eastwood, terse and tight-lipped, smoking, spitting, putting down his drink and then riding off into the sunset etc etc etc. That stereotype has tipped over into Western-inspired films of revenge such as the Mad Max movies or Drive (2011). Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samouraï (1967) and Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999) likewise take up this trope of the solitary man, a person of few words, wedded to his job as a killer, who lives an existence on the fringes of society. I think there is a certain poetry to be found there, because to describe a connection is a necessarily more dialectical endeavour, bringing about all kinds of possibilities and ideas, whole avenues of interpretation and narrative; loneliness is (apparently) simple, shorn of everything else. Its sounds and gestures are short and clean.

Meanwhile, Wim Wenders — a poet of solitude, whose films are drenched in a kind of soulful yearning — took on the great American West in Paris, Texas (1984) for his story of a man only slowly emerging from a period of great aloneness, and whose ability to connect with others is possibly severed forever. That setting feels natural for this narrative, and yet Wenders also made it work for Wings of Desire (1987), in which a Berlin still wounded and in mourning seems to offer the perfect backdrop for its protagonist’s weltschmerz.

In these films, I suppose the hallmarks of that solitude are to be found in costuming and mannerism: I have in mind a frail silhouette, smoking a cigarette; jeans; dispassionate eyes and a low drawl. And wide open spaces — the great sprawling desert all around, rocky mountains and dusty roads. Tumbleweeds. I think that film, clearly more than other mediums, is able to find those deep contrasts in time and space, and to isolate a protagonist; to inscribe him (or her!) within a growing iconography of solitude. Novels of course have interiority, but it may well be that a lack of interiority is helpful in signifying that isolation, because we ourselves view a character from a distance, and are unable to bridge that gap, however empathetic we may be. Seeing a character imprisoned within their own loneliness, at a remove from ourselves, only reinforces that sense of their plight.

I want to mention two other films that came to mind, which centre lonely women whose isolation is all the more heartrending for taking place within society. The first is Terence Davies’ film about Emily Dickinson, A Quiet Passion (2016), and the second is Mia Hansen-Løve’s film about her mother, Things To Come (2016). Both films feature women coming to the end of a relationship that has meant the world to them, and dealing with a resulting loneliness and grief; both women are brilliant, highly educated, independent, at times headstrong. Emily Dickinson is far more wayward as a character, given to fits and tantrums, and Cynthia Nixon is quite brilliant in the ugliness that she lends to Dickinson at these times: her self-pitying, totally shameless, rather distasteful behaviour rubs up against the politesse of her society, and Terence Davies makes sure that it is also unpleasant to us, this spectacle of her misery. He is particularly clever in contrasting these lonely later times with Dickinson’s rather flighty earlier years, all games and bon mots: how arduous and how heavy is her later fall from that state of grace, lumbered with her sense of aloneness.

As Nathalie Chazeaux, the character loosely based on the director’s mother in Things To Come, Isabelle Huppert instead leans inward, and Mia Hansen-Løve brilliantly depicts her solitude within groups of people: her own family, chatting around the dinner table; or a group of young philosophers to whom she is unable to connect. The end of her long-term relationship weighs on her heavily, and nobody can quite understand how this isolates her, how it sits with her at all times, even when her mood is lighter. For Nathalie, the question of her life as it is now realistically set to be forever, namely on her own, is a daunting one, and it is a question that she cannot simply reflect on dispassionately, no matter her brilliance as a philosopher. One scene from the film always comes back to me. Nathalie goes for a walk in the mountains, in the height of summer. Everything is green, the grass is long, and she gazes at the view across the valley, transfixed. But, stopping for a moment to admire the scenery and find somewhere to sit, she decides to settle somewhat in retreat from the majesty of this view, a little further back, on a flat, boring patch of grass. I think this scene, which is over in the blink of an eye, is about somebody working out her place in the world: here it is, big, perhaps forbidding, perhaps glorious; but her part of it, the one she needs to be in, must necessarily be smaller. It must be safe, and gentle. Perhaps it will be boring, even. But this stretch of grass is right, for whatever reasons.

These depictions show women isolated in company, because historically it has not been the case that women can up and leave; they must contend with their role in society, which asks them to be love interests, mothers, home-makers, assistants. Though these women are independent to different degrees, and kick against the demands of their sex, they find themselves brought back to these roles from time to time. These films are chamber pieces to a great extent, although Hansen-Løve is also adroit in filming public transport uncommonly well: Isabelle Huppert crying on a bus is a sight that cinema greatly needed, it turns out. Nathalie lives it all out in public, and it is there that she aches, there that she struggles; around her life goes on, busy and uninvolved.

Send your questions anonymously to Caspar at this link, no personal information is collected.