Psycho. #54

An individual voice.

Many great film-makers both write and direct, including writers who turn to directing in order to have more control over their films. But among people whose work you enjoy, are there any directors you wish didn't write, or writers whom you'd rather didn't direct?

I’ve found it fascinating, with this column, over the course of the last year or so, to start my thinking process with a question rather than, as had always been the case beforehand in my journalism and commentary, being led by some thought of my own and building an argument from there. I didn’t guess that I would find the format so stimulating and generative: silly of me, really, as in life I tend to seek out others and engage with their ideas, and find enormous reserves of interest in responding to different perspectives, seeing down what paths a dialogue can lead me. Fairly often, the question I receive for this column leads me to contend with a line of thought that I hadn’t considered, a perspective that is so far from my own outlook.

This reminds me of a moment that struck me so forcefully as a young adult, when I discussed Jonathan Franzen’s book The Corrections with my mother, and found — which I had not thought possible — that we had responded to a particular passage in the book in diametrically opposite ways. As I understood it, this passage — an argument between Denise, a young woman, and her mother, Enid — was only legible one way, with Enid as the wrong party; everything Franzen had written seemed to show this clearly. And yet my mother sided with Enid, and was just as adamant that this had been Franzen’s intention, that the text showed this clearly. Of course I knew it was possible to have different interpretations of a film or book or work of art — I’m not completely stupid — but I thought these would be more to do with disagreeing over the quality of something. My mum and I were in agreement that the book was excellent, but we disagreed about what it was doing; and the fact of our having totally different readings marked me. All of this is to say that I have looked and looked at your question, and tried to get into its mindset, but I find that I cannot. It’s too different from my own way of looking at things, and I think that my best possible response to it is to try and reframe it in some way, or to reject its terms in order to start again in a way that makes sense to me. What keeps tripping me up, here, is your caveat “among people whose work you enjoy”: because, without it, I could fairly easily name directors whose writing I dislike (Wes Anderson, Quentin Tarantino) and — less obviously — writers whose directing I find wanting (Alex Garland). But for me, writing and directing are quite clearly bound up, and I find it natural to dislike the filmmaking instincts of a director whose writing rubs me the wrong way, and vice versa. Likewise, the directors I like are usually good writers, because I admire the way they translate their ideas into visual terms, and pace their narrative, etc etc.

As it happens, on the day I sat down — and failed — to write this column, I revisited Code Unknown (Michael Haneke, 2000), which I had not seen for perhaps twenty years, and again admired it greatly, with a couple of reservations and question marks that I found it very pleasurable to swish around in my brain. Code Unknown is about the events that mostly stem from one simple action in the film’s opening scene, where a young Black man confronts a white boy who has disrespected a homeless woman. Haneke’s screenwriting is excellent (his ear for conversation perhaps a little less so, being sometimes a bit stiff, a scintilla too high-flown for the ‘ordinary’ situations he describes), because it is all-encompassing and provides structure; it is in a fruitful dialogue with his filmmaking, informing blocking and camera movements. That intelligence of his screenwriting is visible in Code Unknown’s elliptical storytelling and in the immaculate rhythm of its narrative, alternating long one-shot sequences with shorter, starker segments. Because each section cuts to black, often mid-dialogue, the audience is primed to expect a certain length in each scene, and those expectations are either met or dashed; Haneke dispenses information or withholds it. In one stark scene, we find ourselves observing a character in a moment of total despair, and the film seems to suggest that he will kill himself; we think that he must, surely, kill himself, because the film has not yet cut away from him, meaning that some event must still be in reserve — but this moment does not come. Instead, we remain with this man, who must carry on with his life. This is a product of Haneke’s writing and directing at once, and the scene’s genius comes down to pacing, which gets right to the heart of the man’s quandary. It opens with a sharp shock, suggesting further drama to come, but then continues in one single take, bathetically, as nothing further occurs except the man lighting a cigarette. Writing and filmmaking are coterminous here.

Looking up some writing on the film, later on — and still mulling over your question — I came across an interview with Haneke by Hillary Weston, featured on the Criterion website. Weston asks Haneke about whether he conceives a film visually as he’s writing, and he says:

The films that have motivated me, impressed me, and left a mark on me are films made by authors—directors who also write their own scripts. When they’re writing, they know who is going to be directing their script, and they have in mind what the final product will be. (...) For example, in Code Unknown, there is a scene that consists of a series of very long takes that last about ten minutes. It’s a very complicated scene to set up, and it would have been impossible for me to write it if I wasn’t directing it, just as it would have been impossible to direct it if I hadn’t written it. When I was writing I was thinking about how I was going to stage it, how I would direct that scene. If the person directing isn’t the person writing the script, then you’re in a situation where you’re creating something that’s more conventional, where you’re not taking risks.

The long single takes in Code Unknown are essential not just to the rhythm of the film, but to its very intent, which is to sound out human (mis)communication; the ways in which we meet but do not connect. In the brilliant opening scene where Anne (Juliette Binoche), an actor, meets her nephew — the young white boy who cruelly throws an empty paper bag into the lap of a begging woman as if she were a human bin — we open with the pair of them while they chat, but then the camera stays with the boy as he commits his wrong, and then another character comes in — the young Black man — and suddenly we’re in a different film altogether; and all the while Haneke is tracking alongside the pavement, his camera at a somewhat clinical distance but also somehow getting involved in the melee, pulling focus, teasing out the four characters who have been brought together for a moment but who will never again connect with one another.

Nick James writes, about this scene: “Haneke is a true cinephile, and he understands the French debates around the morality of tracking shots [NB: James is alluding to a tracking shot in Gillo Pontecorvo’s war drama Kapo, which Jacques Rivette criticised as being immoral], how their misuse will tend to sensationalize horror; it is sufficient in this case that the camera follows the action as if it were a proscenium arch on wheels, that the very length and consistency of the shot make it feel simultaneously realistic and fabricated.”

Yes. Haneke’s language here is filmic, because his completely dialectical set-up informs the way he shoots the sequence, and vice-versa. It is astonishing to consider that the onlookers in this scene, filmed on the streets of Paris, are extras, blocked and directed just so. Back to Haneke, this time answering a question about Robert Bresson and his influence on him:

The fact that he had the ability to invent a personal, unique language that reproduces his way of perceiving the world—that’s something very difficult to do. Most filmmakers take cinematic clichés and use them as building blocks for their movies. But finding an individual voice, a signature for your work, is extremely difficult, and there are only a few filmmakers who have been able to do that.

There can be no doubt that Haneke ultimately found a unique language of his own, most obvious in his use of long shots and depth of field, trusting his audience to pick out information in a tableau, and not spoon-feeding us by guiding our gaze. Now, the idea of filmmakers finding their own individual language must exist discretely to your question: as Haneke notes, the directors who have managed to do so are far and few between, and most other filmmakers use tried and tested building blocks — or what Haneke rather severely calls clichés — to construct their stories. Establishing shots; shot and counter-shot for dialogue; close-ups at moments of tension or emotion; perhaps a crane shot as a character finally rides off into the sunset: all of these are clichés in the very strictest sense of the term, because they are used over and over again, obvious elements of language that we recognise and which carry information we can easily understand.

Send your questions anonymously to Caspar at this link, no personal information is collected.

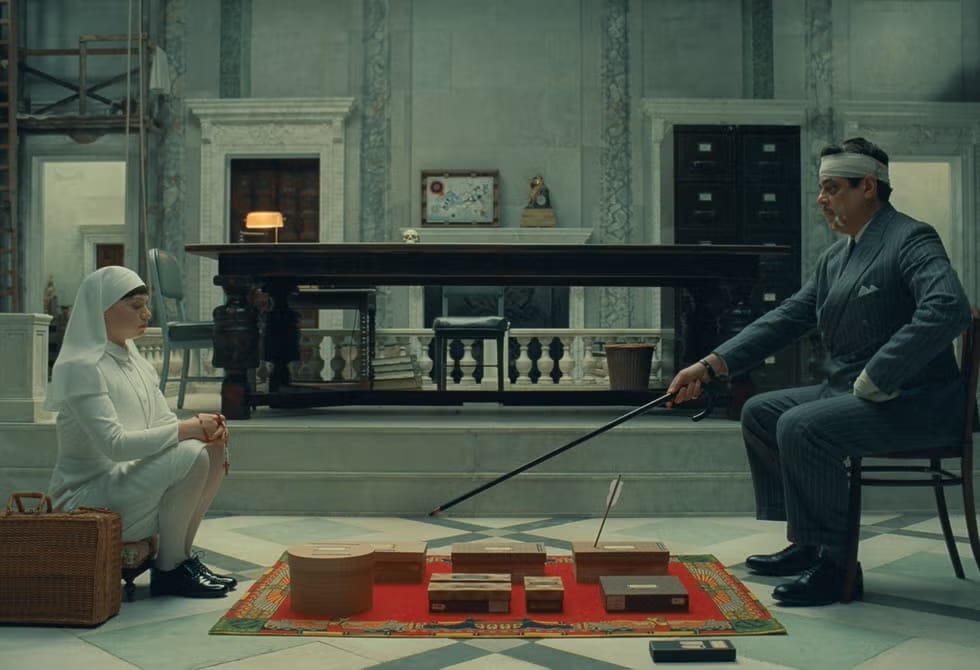

In Wes Anderson’s work, what drives me crazy is that the camera and writing speak the same language, which I find smug: a sideways panning movement to cap off a supercilious joke; a character intruding on a shot from the side, upsetting a perfect symmetry in order to signify an element of fanciful chaos. This is facile, and tired now. Did Anderson find an individual voice in his filmmaking, to return to Haneke’s phrase? It’s hard to argue that he didn’t — but I do not like that voice; I find it grating and inward-looking; it doesn’t challenge itself, or engage with a world outside of its own perspective. The proof is that when, in The Phoenician Scheme (2025), the nun played by Mia Threapleton lays out a number of items and documents on a table, she places them with immaculate geometry, to fit the director’s frame: she is therefore not a character, but a vector. So, yes, that is a language; but it does not speak to me. Perhaps you have a point, that if Anderson was forced to contend with another person’s language he would be forced to open out his filmmaking concomitantly. That feels quite crazy to speculate about, however.

The directors I like write well for the films that they make, and in the case of the very best of them, they seek their own terminology for what they want to get across. I’m thinking of Apichatpong Weerasethakul and his extraordinary writing of silences; of Fassbinder and Cassavetes, of the grace and oneirism of L’Atalante; Godard, certainly, and Méliès. The writing by these directors — and by writing, as I hope is clear by now, I don’t mean only dialogue, but the conceiving and shaping of a film in its screenplay — is necessarily informed by a vision for the appearance of a film, for its construction in filmic terms. Todd Haynes hasn’t written an original screenplay for a long time, and I wish he would return to writing, because I believe that his filmmaking would reflect a more focused intent. May December (2023) is a wonderful film, and Carol (2015) is likewise a fine thing, but with both there is an inescapable sense that the filmmaking voice is in service to something, is completing a job for someone, is decorating words. What did his screenwriters envision? Haynes has ideas galore, but I think that organic quality, the interplay of language, leads to a truer style, a greater clarity of voice. This isn’t to deprecate all directors who don’t write their own screenplays: I don’t have the space to rehearse the whole auteurist debate here, and also can’t be bothered. My preference is simply for that clarity, or coherence of tone.

Send your questions anonymously to Caspar at this link, no personal information is collected.