Queer Subversion in Art and Life

The ways in which the stories of three queer artists and groups are brought to light offer a fuller understanding of what it means to be queer

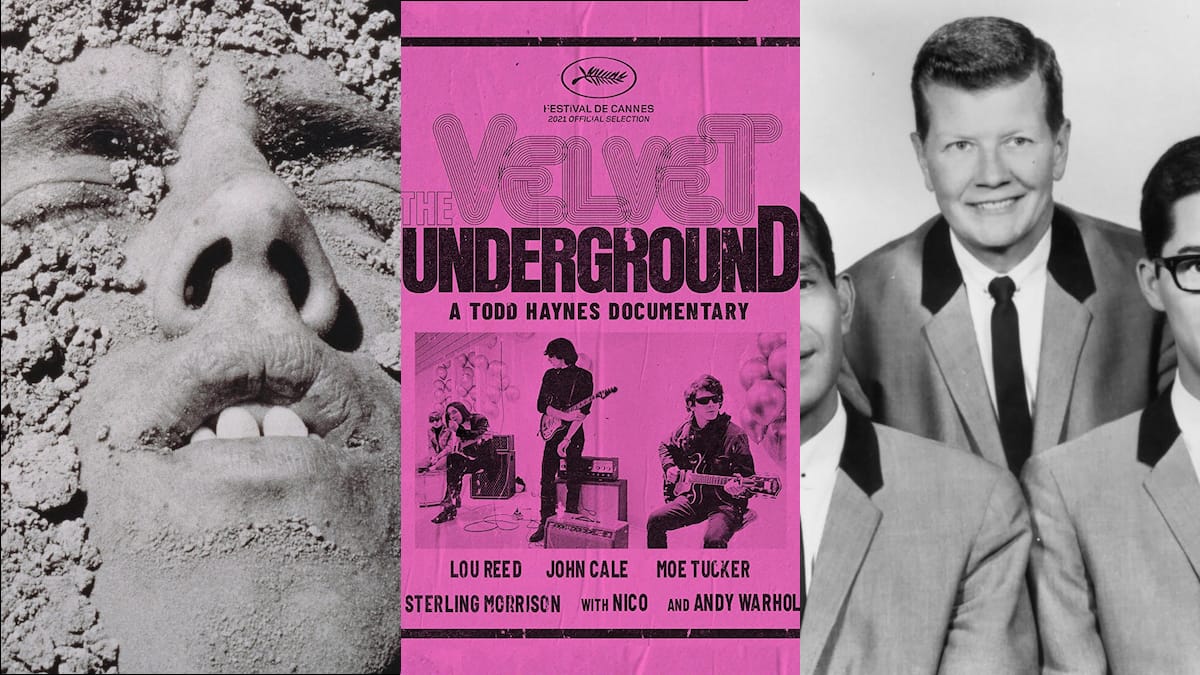

Three documentaries released in 2021 — Wojnarowicz: F**k You F*ggot F**ker, The Velvet Underground, and No Ordinary Man — examine queer artists of the 20th century. More than just biographical portraits, they are portraits of artistic subversion and resistance. Each of these artists existed outside the mainstream, and each film handles their outsiderness differently. Using distinctive formal techniques to approach their subjects and their cultural contexts, these films trace a lineage of transgressive queer artistry.

Chris McKim’s Wojnarowicz: F**k You F*ggot F**ker closely tracks the entire life of artist, writer and AIDS activist David Wojnarowicz, using archival materials, animations of his artwork, and interviews (primarily in voiceover). McKim’s narrative approach foregrounds Wojnarowicz’s righteous anger, as both a marginalised political subject and individual who suffered hardship and abuse, while its aesthetic approach centres Wojnarowicz’s artistic and literary style. Yet in animating his subject’s colourful multimedia paintings and collages, and using his intimate, incendiary writings in voiceover, McKim’s film portrays a man whose art and activism were closely intertwined.

McKim approaches Wojnarowicz with aesthetic and biographical interest in his radical politics and artistry, as is immediately clear from the film’s opening sequence. Onscreen text informs the viewer that Wojnarowicz’s art came from his own experience, and the moments that follow suggest the artistic direction his experience begets: In voiceover, Wojnarowicz intones “We rise to greet the state, to confront the state” as an American flag billows across the screen in black and white. Text appears on the flag, reading:

1989

AIDS is a full blown epidemic

Queer art is under attack

An image of red blood cells appears and gives way to a rickety roller coaster, and we hear Wojnarowicz state: “When I was diagnosed with this virus, it didn’t take me long to realise I’d contracted a diseased society as well.”

By beginning Wojnarowicz in media res in 1989, McKim marks the time as a significant moment in his subject’s life and career: diagnosed with AIDS in 1988, he dives headfirst into AIDS activism, his work draws public attention and political condemnation, and his artistic practice reaches a fever pitch of life-or-death urgency. The images McKim uses add to this snapshot of Wojnarowicz by mimicking his aesthetics: Wojnarowicz frequently collaged seemingly-unrelated images with provocative political and sexual connotations, and McKim’s use of montage savvily recreates this technique for film. Not only providing context and a taste of Wonarowicz’s literary and artistic style, McKim’s opening images tell the viewer that Wojnarowicz’s art is inextricable from the oppression and political violence that he experienced as a queer man. Drawing from the archive of Wojnarowicz’s life and art, McKim and editor Dave Stanke place these artifacts together so that they build upon one another, ultimately creating a portrait of Wojnarowicz as a singular artist whose queerness shaped his aesthetic and political radicalism.

In The Velvet Underground, Todd Haynes and editors Affonso Gonçalves and Adam Kurnitz also use memorable editorial techniques to contextualise archival materials, but to different ends: instead of examining a single artist, Haynes takes a broad view. While the film dutifully depicts the lives and careers of the Velvet Underground’s members, Haynes’ bigger project is to interpret the way New York’s downtown artistic scene of the 1960s created the ideal conditions for the group to emerge. Said Haynes in an interview, “I knew I wanted to tell a story through the late-Sixties experimental vernacular…where the music and images lead us, not the words.” Rather than rely solely on talking heads to provide context, as a more conventional documentary might, Haynes uses images and sounds from music, cinema, and performance art that influenced or interacted with the band, often juxtaposing them in split screen. Of course we see Lou Reed and John Cale and hear the band’s signature songs, but we simultaneously see flashes of Jonas Mekas’ and Jack Smith’s films, and hear La Monte Young’s distinctive droning music. Andy Warhol, who managed the Velvets and added German singer Nico to the group, is particularly baked into the film’s form — cinematographer Ed Lachmann has noted that the split-screen techniques were borrowed from Warhol’s film Chelsea Girls, and the interviews were filmed in the style of his Screen Tests.

This artistic movement was dominated by queer creators and aesthetics, including Warhol and Lou Reed, who frequented gay clubs and wrote poetry about his gay, kink-driven sexual encounters. But again, Haynes does not solely examine these subjects’ queer identity in order to form straightforward narratives about their lives, but to contextualize them within the social and artistic milieu they participated in. One short yet rich sequence pinpoints the association of queerness to this milieu, in conjunction with the state oppression and police violence that bore down on queer life at the time. With the instrumental backing of “All Tomorrow’s Parties” playing in the background, Haynes deploys a montage of middle-aged white men calmly denouncing gay sex in public-facing media (one is a news anchor), interspersed with footage of the police raiding a gay club. Most of the patrons cover their faces, but one man, wearing a wedding band, stares straight into the camera, flips it off, and blows a kiss. As this occurs, we hear music manager Danny Fields echo this casual dismissal of the cops’ power, commenting “you know, we got arrested for being in bars. But so what? It was part of it.” He goes on to describe the social scene at the San Remo bar: “everyone seemed sort of gay, extremely smart and/or creative. And they turned out to be Edward Albee and Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns. And at the center of it is the exploding art world. Money, parties, power.”

In this sequence which doesn’t even directly reference the Velvets, Haynes therefore illustrates the centrality of gay men to the artistic boom in mid-1960s New York, and how Reed and Warhol’s involvement in this creative queer scene led to the development of the Velvet Underground. (John Cale, though heterosexual, was intertwined with this milieu as well, sharing an apartment with gay avant-garde filmmaker Jack Smith). Haynes indicates here, through his choice of footage and interview subject, that despite state oppression and hateful public opinion, queer social groups in that specific context formed with relative ease and created the grounds for some of the most consequential art of the decade. Though its members were predominantly heterosexual, Haynes makes clear that The Velvet Underground’s emergence is inextricable from the queer artistic flourishing of this time and place.

Chase Joynt and Aisling Chin-Yee’s No Ordinary Man centers a subject who, unlike Wojnarowicz, Reed or Warhol, apparently had little-to-no contact with queer communities and could not openly discuss his identity. Billy Tipton, who was a transgender man, was a successful jazz musician who retired from his performing career in order to marry and adopt three children. His gender identity was revealed without his consent after his death, and his family was subjected to a sensationalised press cycle that framed Tipton’s transness as a deception. Working with a cryptic subject and with limited materials from their life available, Joynt and Chin-Yee use the open-endedness of Tipton to their advantage. As Joynt puts it, “I think we knew from the start that the questions of our project needed to be much more complex than, 'What might it mean to tell a story about Billy Tipton?' Instead, we had to think: what does it mean to be thinking about a history of transmasculinity?” In a thematic sense, this may be the most ambitious of the three films: while Wojnarowicz focuses on a singular artist’s life, and The Velvet Underground contextualises an influential band in their artistic milieu, No Ordinary Man uses the story of a trans musician to analyse cultural perceptions of transmasculinity.

To consider contemporary transmasculinity in the context of Tipton’s life, Joynt and Chin-Yee’s main formal devices are discursive interviews with an array of transgender scholars and creatives (in addition to Tipton’s son, Billy Jr.), and mock “auditions” for a fictionalised retelling of Tipton’s life. We see numerous transmasculine actors embody Tipton, each reading from the same set of scripts, but bringing personal experience and individual interpretations to the role. These auditions create both the opportunity to examine the individual experiences of contemporary transmasculine people, and to question what Tipton’s feelings were as he navigated his career.

One striking scene shows actor Marquise Vilson reading a scene that begins with a colleague telling Tipton that he “heard a rumor.” Vilson describes the potential terror of being a closeted transgender man in the year 1954, and being told from an acquaintance about a “rumor” — the “rumor” could be the one that outs you to the public. Vilson describes his own experience with conversations like this: “Shit, am I being read right now? Are you about to out me? Are you gonna tell me something about myself that I already know?” This moment connects contemporary transmasculine experiences with speculation as to the experiences of a transgender man in 1954: Vilson, and the viewer, are left wondering what Tipton may have felt as a transgender man whose career could be undermined at any second by an unconsented outing. While the context of Tipton’s own life is incomplete, Joynt and Chin-Yee use these audition scenes as a tool to imagine his possible thoughts and feelings, and consider what connections we can draw between Tipton’s story and contemporary trans experiences.

Other scenes indicate more straightforwardly Tipton’s influence on contemporary transgender life. Late in the film, we see activist and author Jamison Green show Billy Tipton Jr. an article written by the late trans activist Lou Sullivan, who wrote that “Tipton did it on his own. At age 74, he died as one of our grandfathers. Men like Billy prove that we FTMs are not a bizarre recent phenomenon; that throughout history, there have been females who knew deep down that they were men and did whatever they had to do to live their lives honestly.” The film ultimately argues for Tipton’s influence as a transgender individual in a cultural moment when transgender experiences were only acknowledged as salacious stories.

Rather than straightforward portraits of their subjects, each of those three documentaries is carefuly to underline the extent to which outsiderness pervades these lives, and consequently much of the history of queer artistry. Each centers queer artists who stood apart from the dominant culture of the times they lived in, whether in art or in life, and carved spaces for themselves despite the considerable challenges. The filmmakers are acutely cognisant of their subjects’ separations from dominant culture, and how their queerness shaped their outsiderness. Most immediately evident is Wojnarowicz, where McKim centralises the political oppression faced by queer people that escalated to mass death during the AIDS pandemic — Wojnarowicz responded by creating art that consistently challenged and provoked systems of power, and McKim makes good use of his subject’s writings in which he articulates the falseness of the “one-tribe nation” the United States purports to be. In his film, Haynes illustrates the multivalent art created in a predominantly queer milieu, with the Velvets’ experimental, sometimes-atonal pop music as a prime example, showing how it arose organically from subcultures and didn’t find immediate commercial success. Billy Tipton’s outsiderness, meanwhile, was covert — with a successful career as a jazz musician in live performances and recordings, and a retirement from performing characterised by a quiet, loving home life, Joynt and Chin-Yee examine how Tipton’s concealed gender identity marked him as separate from dominant culture only after his death (and, through “auditions,” examine how Tipton may have felt separate).

Through these three films, one can see how each subject subverted the norms of dominant culture and resisted cis- and heteronormative standards — courting controversy and dissent at the time, but creating legacies that remain powerful. By using incisive formal techniques to express their subjects’ lives and impacts — David Wojnarowicz’s own idiosyncratic voice as narration, dense montages displaying the vibrant queer life of 1960s New York, “auditions” which lay bare the multivalent interpretations of Billy Tipton’s life — the filmmakers give context and weight to their subjects’ lives and work. We see their queer outsiderness as both an effect of exclusionary systems, and a source of artistic creation. Despite notable distinctions between the films’ subjects and approaches, Wojnarowicz, The Velvet Underground, and No Ordinary Man collectively further our understanding of what it means to be a queer artist.