Whatever Happened to Utopia?

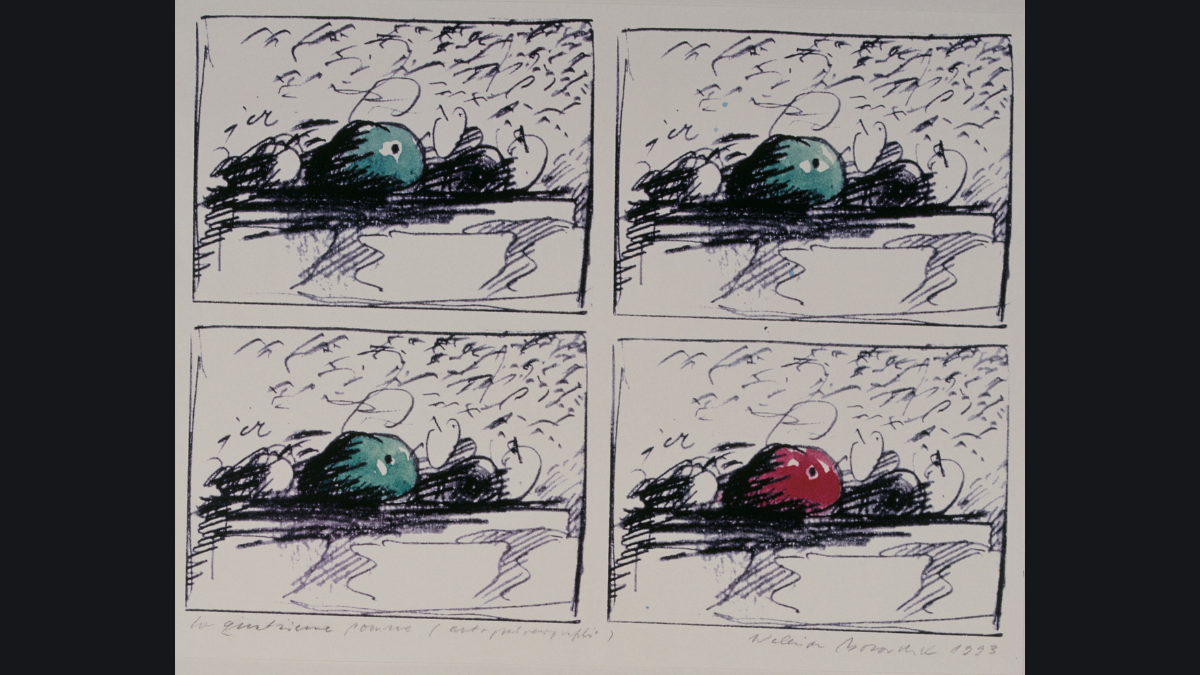

On Charles Fourier, Dušan Makavejev, sex, and communism (pictured: La Quatrième Pomme (1993), © Friends of Walerian Borowczyk)

1973.

A filmmaker from Yugoslavia, let’s call him Dušan, is in trouble.

He made a film, a personal response to a radical psychoanalyst, which was banned. Dušan compared the people who banned his film to Stalinists. Now they want his blood.

He receives a blow to the head.

CUT TO BLACK

Head sore, Dušan comes around.

It’s not 1973, but 2023.

The Soviet empire is long gone. Yugoslavia is no more. There have been wars in the Balkans.

The cinema in Belgrade that once screened Dušan’s films is now occupied by squatters.

What is a filmmaker to do?

Head to Cannes.

Get money to make a film.

Problem:

A film about what?

For whom?

Dušan walks the streets of Paris.

He finds himself on Boulevard de Clichy, standing before a large, silvery apple. It’s a contemporary sculpture, by Franck Scurti, dedicated to the utopian socialist thinker, Charles Fourier.

Fourier broke history down into four apples.

The first apple is the one eaten by Eve.

The second is the golden apple (the one Paris gave to Aphrodite).

The third is the apple that fell on Newton’s head.

The fourth apple is the one Fourier noticed costing more on the city street stall than it did to grow in the countryside.

All but one of Fourier’s apples are bad.

The first concerns biblical notions of sin, the second bloody conflict, the fourth damned capitalism.

Only the third apple is good. Newton was concerned with the laws of attraction; Fourier sought to extend this to people.

He believed that the form of economic, political, and social life should itself be changed to accommodate the passions of the individual.

After all, these economic and social structures were man made, not God-given.

If Dušan’s previous film was a personal response to a radical psychoanalyst, why should his next film not be a personal response to a utopian socialist?

It is a film, Dušan thought, that the viewers of 2023 do not want, but need. It is economics, politics and society that are making the people in the street unhappy.

If only he could show, through the medium of cinema, that viewer’s passions, like cinema, were God-given.

Only by pursuing passions, Dušan, like Fourier, thought, will these miserable people achieve something akin to universal harmony.

As with his film about the radical psychoanalyst, Dušan decides not to shy away from Fourier’s more outré ideas, outlined during his final decades.

Like people living for 144 years.

Or new species of animals, like anti-lions.

Or humans developing prehensile tails.

Or the ability for souls to migrate between physical and aromal worlds.

After all, special effects are much better now than they were in 1973, and besides, everybody seems to love this film called Avatar: The Way of Water.

Fourier’s writings, Dušan remembers, were edited by a French woman, Simone Debout-Oleszkiewicz.

She was a resistance fighter during the War.

She also had an extensive correspondence with the pope of surrealism, André Breton, who was similarly fascinated by Fourier’s ideas.

Six years before the bang on Dušan’s head, the year before those May riots, not to mention the Summer of Love, Debout edited an incomplete, late work by Fourier that had been known about but unpublished.

It was called A New World of Love, in which Fourier outlined his vision of utopia as a perpetual cycle of public, ritual orgies.

If he was still alive, Dušan’s friend George Melly would have said: ‘This is Cinema!’

Careful to avoid the conductor, Dušan makes his way down to Cannes on the TGV.

After all, his passport, issued by the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, expired back in ‘75.

He doesn’t have much in the way of money. By chance, he met a lazy student who was willing to pay hard cash for Dušan to write his thesis on the Yugoslav Black Wave. Žika Pavlović, Aleksandar Petrović, Želimir Žilnik, Mika Antić, Lordan Zafranović, Mića Popović and Marko Babac – Dušan knew these guys.

So, there Dušan was, once again, on the Croisette.

The last time he needed money, he approached a Bavarian TV station to give him both a crew and a budget to shoot some documentary footage, and then went to a local company, Neoplanta, to expand it.

Luckily, Dušan meets a young woman from the East.

Her name is Dobrotka, she’s a Pole.

Dobrotka is what the French call a pique-assiette. She goes from buffet to buffet. Happy hours and parties, scheduled with military precision, on a napkin.

After modelling but before the breakdown, she studied philosophy at Warsaw University. She planned to do her thesis on Fourier but didn’t know French.

‘Why?’ asks Dušan.

‘Because I want a tail.’

Dobrotka gets Dušan into the festival’s market village, a vast warren of temporary, anonymous pavilions.

They head straight to the Serbia Film Commission.

Forty, bald, and having a fifty-year gap in your IMDB profile is not a good look. An official looks up the Cannes Classics listings, to see if anything by Dušan is in the year’s line-up. No luck.

***

Back in the day, Stalin said that applying the principles of Communism to Poland was like trying to saddle a cow. He was referring to the role played by the Catholic church in Polish national identity. That’s why, when he wanted to establish a communist government, he sent Jews.

The Poles responded by equating Jews with communism, or Żydokomuna.

After purging Jews of the communist party, those Poles left were interested in power, and not much else.

Back in the old days, everything was run by the state.

Sure, the odd foreign sale brought in some hard currency.

But by and large, that didn’t matter. Everything was a closed loop.

The state paid the film workers, the spectators paid the state, the state paid the workers, etc.

Things are different now. ‘If you’re not stealing from the state, you're stealing from yourself.’

Now, the history of Poland is a constant battle not to be Russian or German.

Therefore the goal was, if not to be Polish, then French.

And so, when it came to resurrecting the local Polish film industry, the Poles looked to France.

Poland adopts the French model, which is to tax the population in order to subsidise ‘artistic’ Polish films and their promotion.

The only problem for Dobrotka, as a stylish Polish woman, is who decides what is artistic? This is where the rub lies…

Don’t worry about taste, Dobrotka councils Dušan, head over to those holding the purse strings.

As for herself, as one of forty million Poles who pay a tax into a forty-million-euro pot, the act of helping herself to a tote bag, notebook, mug, not to mention the odd vodka cocktail and fistful of smoked cheese, is simply about taking back what’s hers.

‘If you’re not stealing from the state, you're stealing from yourself.’

***

Dušan asks Dobrotka to be his producer.

Dobrotka agrees, for a new film is a pretext for more premieres and screenings, which mean buffets.

‘What I like most is drinking other people’s wine’, says Dobrotka, quoting Diogenes.

It was at this point Dušan realised that he would be sleeping in an upturned bath with a pack of wild dogs.

Dobrotka swiped a copy of Vogue and lamented the days were gone when Yves Saint Laurent would hire Parajanov, or Chanel would employ Iliazd.

Dušan is distracted by the sound of Russian and realises that the speaker is a sex worker.

In his previous film, he fought for the rights of a trans sex worker, in a society that stigmatised them. In fifty years, nothing has changed – if anything, things have gotten worse. He comforts himself with the thought that this is more reason for making his film.

After all, Fourier had turned the problem on its head.

First, he collapsed work into pleasure.

Second, he did away with marriage, monogamy, and the family.

Third, sexual desire and sexual acts were not to be private, but public.

Fourth, there was to be no competition – every individual would be paired in a sequence of transient couplings with their complementary types – i.e., sadists with masochists.

Fifth, nobody was to be left out – the most attractive people would be obligated to couple with the poorest, sickest, and eldest.

Fourier called this utopia Harmony.

Alas, this proves to be the sticking point.

‘We like your positivity, Dušan, but we really think this material needs a female perspective, as well as an intimacy coordinator.’

‘What’s that?’

'They're like a stunt coordinator. But for intimate scenes.’

‘Mise en scène matters.’

‘Not anymore, Dušan.’

‘When Godard referred to tracking shots as being moral issues, I don’t think this is what he meant.’

‘Godard is with God.’

The advice gets worse.

‘What are the rules in Harmony? How is justice maintained?’

‘There are only two sins – monogamy and sex in private.’

The manager/producer thinks most of his clients will have to be cast against type.

‘There’s a giant, celestial mirror, orbiting the Earth, that exposes the crime of monogamous couples secretly having sex,’ Dušan adds.

The manager/producer gets an idea: ‘Perhaps the heroes can be a couple, who defy the system by having a monogamous relationship behind closed doors.’

‘That’s not the point.’

The manager/producer pours Dobrotka another glass.

‘Look, it’s a win-win situation. You get to have your sex scenes and we get to keep the bible belt.’

It is at this point a cauliflower-eared heavy asks Dušan and Dobrotka for their market accreditation.

Both find themselves turfed out onto the Croisette, along with all the other dreamers.

***

Pierre Mac Orlan was a songwriter, who also wrote pornography.

He had a penchant for flagellation.

He wrote Le Quai des brumes, which Jacques Prévert adapted for Marcel Carné.

What's more, Orlan wrote one of Guy Debord’s favourite books, Petit Manuel du Parfait Aventurier.

In this book, he put forward the idea of the passive and active adventurer.

The passive adventurer re-imagines and recreates the world as a dream.

The active adventurer, meanwhile, travels from place to place, seeks out novelty, and tries to find and lose themselves.

Coming up with an idea for a film, like Dušan, is a passive adventure, while financing, making, and promoting a film is an active one.

***

Dobrotka is a splinter - someone and something to be either absorbed or rejected.

An alien, in as much as she is alienated.

A victim of a repressive tolerance — a society that tolerates mind altering drugs, so long as they don’t alter your mind; one that tolerates casual sex, so long as it is just that and nothing else.

What the radical psychiatrist of Dušan's film was trying to tap into were drives, or what Fourier called passions, twisted out of joint by oppressive societies.

Unleashing those drives can be frightening, as they were for Dostoevsky and Freud.

It could also be, Dušan thought, exciting.

Before Dušan was born, Eisenstein was in Mexico, developing an idea that art acts like a drug, one that makes us think pre-logically.

Mickey Mouse is not either a boy or a mouse, but both.

Bad acting is when you see the actor or the character, not both.

Dušan began to suspect that, during the half century he was unconscious, cinema died, and that what he was now witnessing was a zombie cinema - neither living nor dead, but somewhere in between.

Perhaps the manager/producer was right — nobody cares about mise en scène.

Mise en scène, however, is a term that existed before cinema.

There are directors who can’t direct, just as there are people who aren’t directors who, nevertheless, direct; there are actors who can’t act, just as there are non-actors who act (like Dobrotka).

Cinema existed before cinema, just as it exists after cinema.

When Dušan was twenty, Henri Langlois, founder of the Cinematheque francaise, visited Belgrade, with fifty-two films from the collection.

Entr'acte, Un chien andalou, L'Âge d’Or, the Soviet classics, and, most importantly, Vigo’s films, À propos de Nice, Zéro de conduite and L’Atalante.

Vigo was the rebel.

Who or what, today, is Dušan to rebel against?

Not the Stalinists, that's for sure.

Dušan remembers what Cocteau said, that cinema would become poetry when camera and film cost as much as pencil and paper.

All that matters are words, images and sounds.

The possibilities are endless.