When My Ship Comes In

Martin Scorsese's film presents a model of woman- and motherhood as tender as it is strong

Only the fourth of Martin Scorsese’s dozens of feature-length narrative films, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore has become somewhat overshadowed in his catalogue simply due to the stature of the repertoire he has created ever since, and despite the fact that it was relatively well-reviewed upon its release and later nominated for three Academy Awards, including a win for Ellen Burstyn’s titular performance. In a filmography characterised by shady deals, mercenary sacrifices, and sprawling epics, the comparatively smaller stakes of Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore make it a visible outlier in an oeuvre of such portentous, decidedly masculine odysseys, only one of two of Scorsese’s features (the other being the earlier Boxcar Bertha) to centre on a female protagonist.

Yet even that characterisation sells Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore short, for even it possesses the existential scope and the focus on life at a crossroads familiar from any title more immediately associated with the director’s name. To say that the film is “underrated” would be a misnomer as limiting as locating it as a surprising fit in Scorsese’s filmography, but its paradoxical place in that canon has nevertheless led its modern contextualization to fail to fully grasp what makes the film such an enigma. For all of its hilarious, off-kilter one-liners, wielding both cynicism and earnestness with aplomb, the film is rarely labelled a comedy, more often a romance or drama; and despite the radiance of Ellen Burstyn’s character during every second of her story, the nuanced nature of Alice’s strength is sorely under analysed in what little contemporary discussion of the film there is.

***

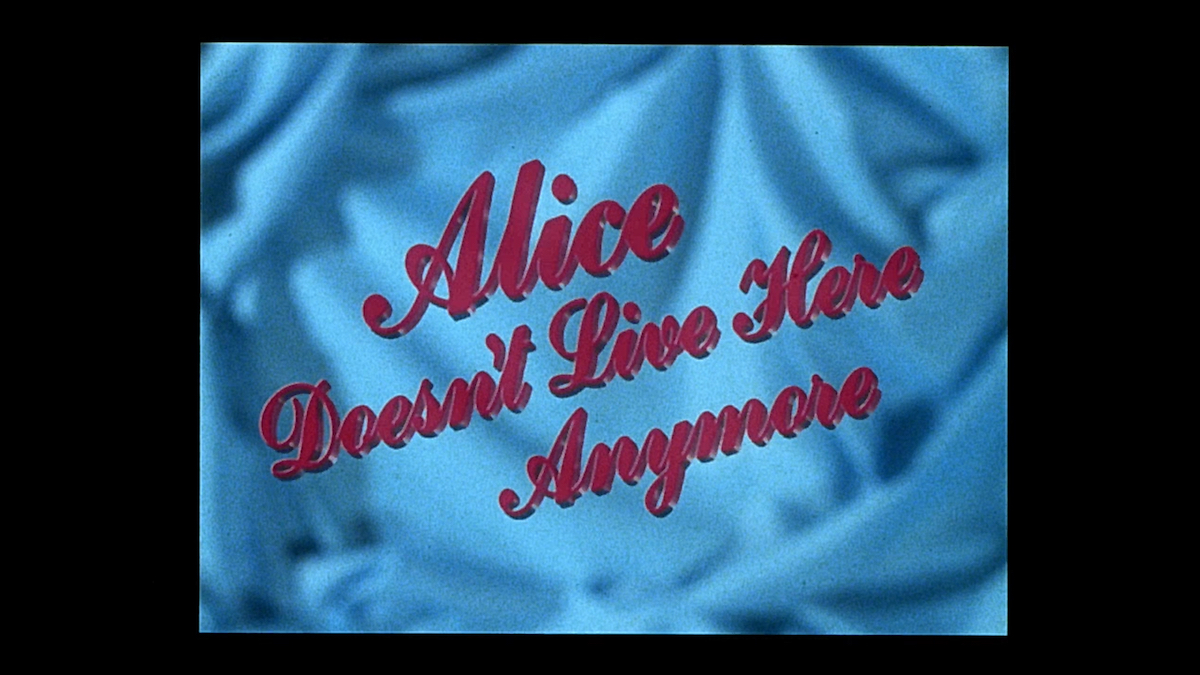

The title sequence of Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore brandishes its credits atop an image of baby blue silk against a cursive font so saturated in raspberry pink that the contrast of colours threatens to strain the eyes. If the visual aesthetic wasn’t exclamatory enough, the sequence is also set to the song “You’ll Never Know,” ripped straight from the Alice Faye rendition of Hello, Frisco, Hello fame, the singer’s yearning vibrato amplifying the tune’s inherent melodrama tenfold. Adorned with a femininity so garish as to approach parody, these first couple of minutes are just the ironic foundation the film needs to set up the first of its many acidic jokes, an introduction worthy of a protagonist as stark as its imagery.

The movie introduces a pre-teen Alice Graham, doll in hand and hair in ponytails, strolling upon a hill a few yards away from her farm house. She quaintly sings the tune to herself as she makes her way home, her mother calling for her to hurry, her dinner presumably awaiting on her arrival. This opening scene could seem jejune and banal, if not for the fact that the set — because it clearly is a studio set — is drenched in ominous red light, a traditionally sentimental setting transformed into a nightmarish inferno. “I can sing better than Alice Faye, I swear to Christ I can,” she mutters, stroking her doll’s head. “You wait and see. And if anybody doesn’t like it, they can blow it up their ass.” In a matter of seconds, the sweet little girl of humble beginnings is revealed to be a blunt, brash firebrand, with the sort of salty determination that defies confinement or any predetermined expectation.

Before the joke even has the time to fully land, the scene cuts, throwing the viewer twenty-five years into the present day. Alice, now an adult played by Ellen Burstyn, has married to become Alice Hyatt, and the fierceness of tongue she once displayed as a child has swiftly been caged into sidelined domesticity. No longer living in her childhood home of Monterey, California, she has moved with her husband to someplace adjacent to Socorro, New Mexico. It is there that she finds herself darting from one corner of the house to another, facilitating the negotiations between her pre-teen son Tommy, who blasts rock music in the living room, and her husband, who can’t stand the noise and blames Alice for supposedly not having the maternal capacity to discipline their child.

However, at no point in Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore is the film’s titular protagonist shown to be weak or docile. Despite the anomaly of her characterisation within Scorsese’s broader filmography, Alice’s womanhood is treated with a uniquely accommodating, thoughtful eye, always ensuring that she gets an opportunity to get a word in edgewise to assert herself, even when she knows she won’t be heard. When, at dinner, one of Tommy’s pranks enrages his father, who smashes the dishes off the dining room table and violently shoos Tommy out of the house before finally stomping away, the camera stays with Alice and shows her indulging in a brief outburst of anger: she bangs her hands against a door, before quickly redirecting her emotion back inwards, breaking into much quieter tears.

Scorsese also lends great attention to one of Alice’s more substantial reprieves from her husband: her hushed conversations with her neighbour, Bea (Lelia Goldoni), as the two make jokes about their love lives and Bea stitches Alice’s dress. Even in this relaxed setting, however, Alice’s cadence is noticeably more subdued than the glimpse at her childhood suggested it would turn out to be: she whispers her cruder remarks, implying sly insinuations about male sexual prowess rather than explicitly saying them. Perhaps even more distressingly, she always takes care to measure her words when discussing her husband, ensuring that his abusive household regime is never thought of as such by her friends. Even in her plight, though, Alice expresses her doubts that she could ever sustain herself without the aid of a man, making her failed attempts to seduce an apathetic sexual partner (her own husband) that much sadder in retrospect.

Not even a minute after making this remark does Alice receive a call that her husband has been involved in a fatal traffic accident, and from there, the grieving process begins: Alice and Tommy are seen in their mourning attire, as tears streak Alice’s wounded, panicked face, equal parts devastated by the past and daunted by what the future might hold. The presumed funeral itself is never shown, but Alice’s dialogue with Tommy is: “Mom, how much money is there left?”

Not enough, apparently — at least, not enough to provide any good reason to stay. Alice promptly rids herself of any possessions that are not absolutely necessary in a yard sale that provides her with little more than pocket change, and, with that, hits the road, Monterey-bound with the vow that she will make it to her intended destination before the arrival of Tommy’s twelfth birthday. Her departure is, once again, teary-eyed, as she gives Bea one final hug before leaving this home for good; that she has actually followed through on her grand ambitions to finally leave the town that brought her so much strife seems to shock Alice as much as it does her peers.

It is while on her own that Alice’s wry sense of humour fully coalesces, her acidic barbs and quick timing becoming immutable when not in the presence of someone to stifle her. As Alice and Tommy travel through the hot southwestern sun on the state’s highways, him bored to tears and her annoyed by his constant complaining, she maintains her composure as well as she can, only stopping to make sharp-edged quips with the same sparring speed as her more vulgar pre-teen son.

Burstyn’s unique candour would be difficult to replicate, much less accentuate, in the hands of any other actor. Her dialogue, whether serious or comedic, is delivered with a naturalism so instinctual that its layers only become more subtle: her Alice is at once rambunctious and vulnerable, her frustration and short temper borne out of bone-deep anxiety around the question of how to care for herself and her child, but a worry that also inspires within her the white-hot passion to trudge through whatever may come her way — a contradictory and almost absurd push-and-pull dynamic that lends her a special integrity of character, and even her most serious moments a slanted sense of humour.

When they finally reach their destination, Alice and Tommy do not arrive at the intended Monterey, but instead at a derelict motel in the middle of nowhere, just outside Phoenix, Arizona. Alice promptly gives herself a makeover, with the stated intention to make herself look younger, and sets out on the hunt for a job, while Tommy stews in youthful boredom inside the motel room. Alice visits bar after bar on the hunt for a lounge singer position, and is met with rejection, if she gets to speak to a manager at all; by the time she finds a bar owner who will help her, she can barely muster a sentence to describe her situation without breaking down into tears. When she is finally relocated to an establishment looking to hire, she sheepishly shambles to the piano, apprehensively tests the microphone, and begins to sing. The precariousness of her search does not deter her from expressing her gift, however; while singing, her voice glides with gentle, wistful elegance, hypnotising the bar’s few daytime patrons.

One of such visitors is the swaggering Ben (Harvey Keitel), who introduced himself to Alice by sliding in her booth during a break, in spite of Alice’s initial rejections. His flashy, extravagant cowboy attire barely disguises his self-deprecating, hangdog demeanour; despite — or perhaps because of — his flirtatious showmanship, he is clearly a very lonely man. He, a bar-frequenting bullet manufacturer, and she, a confused bar singer, find each other at a crossroads, clearly searching for a greater joy in life to ease the dysfunction that is sure to meet them outside the bar. Alice knows this, and she takes Ben home — only, she stops at the door, not quite ready for Tommy to meet him.

Their romance persists, even as Alice keeps her distance, finding a level of comfort in her perceived control of the relationship. Even at her most confessional, she never fully gives away why she’s in her situation, always omitting small details or dodging questions of how she found herself stuck in an abusive relationship with her late husband for such a long time. Perhaps her reluctance to answer these questions stems from the reality that she doesn’t know the answers to them herself. Ben, in any case, doesn’t seem to mind, even having sex with her on occasion at his apartment.

It turns out, however, that he is hiding just as much from Alice as she is from him: one day Ben’s wife, who has by now learned of his infidelity, comes to confront Alice about it. She’s not angry — in fact, she comes begging Alice to abandon this romance, and cowers in fear when describing her situation. Alice, ashamed of her participation in such an affair, gladly surrenders, worried both about Ben’s wife as she is about herself — the parallels between the two women are clear: both find themselves in the eye of the storm of a volatile lover, always on the verge of being swept up in his thunder.

Surely enough, Ben eventually breaks the door’s glass and invites himself in, wreaking havoc on any furniture that stands in his way as he smacks his wife and berates her until she flees the scene. Alice pleads with Ben to calm down, but he only responds by pinning her to the wall and likening himself to the scorpion that lies preserved in amber in his pin: calm when left alone, but prone to violence when provoked.

Once Ben leaves, Alice realises that she, too, must skip town immediately, not just to avoid Ben’s wrath, but because she has once again found herself in a situation similar to the one she fled in the first place. The realisation makes her shiver, but her willingness to listen to her instincts proves that she has, in some respect, evolved from the woman she once was, refusing to bend to trouble even when it promises her a fleeting semblance of connection.

When the next round of Alice and Tommy’s travels eventually ends, they find themselves in Tucson, where the city is different but the circumstances much the same. Alice once again goes on her obligatory job search, although this time she can’t find employment singing; instead, she is hired at a diner, an idea she loathes but knows she can’t reject. Tommy, who knows the two aren’t on track to arrive in Monterey any time soon, is displeased, though he eventually finds time for himself when his mother allows him to attend guitar lessons and befriend the more rebellious Audrey, who is played to mischievous, oddball perfection by a young Jodie Foster.

Alice is the most miserable with this new living arrangement, her new waitressing job even more chaotic than she expected. The diner is cramped, the customers boisterous, and her co-workers barely any help; the shy, reclusive Vera hardly projects her voice loudly enough to be heard by patrons, while the much more audacious Flo (Diane Ladd, who would go on to portray a different type of brazen Southerner in David Lynch’s Wild at Heart) welcomes Alice with an inaugural speech encouraging guests to take a peak at her cleavage but never touch, because, in her words, “you can pull on mine.” Alice is put off by the seemingly spontaneous vulgarity of Flo’s remarks, helped none by the fact that her pay is even worse than before, but instead of surrendering, she simply vents to Tommy about her terrible first day, before returning to the site of chaos the next day.

It is at the diner that Alice meets David (Kris Kristofferson), a downbeat loner who takes interest in her the moment he sees her. Alice definitely finds him attractive, the brooding, rustic sexuality stemming from his occupation as a rancher a potentially perfect match for the wildness that lurks in her heart. But she is more guarded than ever, and David makes a clear effort to show himself as a safe, helpful and loving prospect, ingratiating himself to both Alice on her rare breaks and to her son — a relief for the widow, as Tommy only adds to the hectic nature of Alice’s day in his very vocal boredom.

David and Alice grow closer, and he eventually invites her to his ranch, where she finds herself and her son a natural fit. Yet even in her bliss, her failure to accelerate her life towards her desired position still weighs heavily on her mind; Tommy, as listless as ever, is about to turn twelve, and the two haven’t even made it to California yet, a fact she is well aware of and feels guilty about. The situation comes to a boil when Tommy, annoyed by the lack of attention he is receiving on his birthday, wilfully and obnoxiously disobeys David. At the height of the conflict, David spanks Tommy, slamming the record he places on the living room player against the wall and smashing it to pieces.

Alice, as is now instinctual for her, panics, reprimanding David for his harshness towards her son. But David responds by exposing to light the deeper issue behind this outburst of violence, namely the insecurity that colours their seemingly solid relationship: has she fallen in love with him, or is she still planning on leaving?

Despite her anger, Alice is heartbroken, not only due to the initial shock of such a tumultuous fight, but also because of the hope David presented, a fullness of life and purpose that characterised a stability she’d had yet to encounter on her trip. After Flo, clearly in the midst of dire straits herself, advises Alice to confront David directly about his feelings towards her,Alice does just that. Their conversation, loud enough to be heard by the entire restaurant, is nothing short of triumphant: Alice confesses her love, and David, his dedication, as well as his willingness to sacrifice his livelihood in order to move to Monterey with Alice; in his own words, “I don’t give a damn about that ranch.” Alice, however, when forced to take light of her current circumstances in that fateful moment of choice, realises the presence of her newfound makeshift family standing by her: her son, her co-workers, and, miraculously, David himself. She knows she needs a home, but not much else, all of which David can provide much more practically in Tucson than in her dreams of Monterey. Because Monterey, she knows, is just a dream, a relic from her childhood. With that in mind, she chooses Tucson, and David, too, thus putting an end to her road-tripping search for money, safety and happiness.

Though Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore fully qualifies as a portrait of female empowerment and emancipation, the film’s script is not so reductive as to merely correlate spunk with strength. Alice’s growth occurs in tandem with her willingness to become vulnerable in the company of others — first in private, then finally, in the film’s closing scene, in a sea of many — and finds its apotheosis not in an illusory idea of stubborn and unwavering self-reliance, but the very moment she decides to settle down with a man.

What may look to contemporary, impatient viewers as little more than yet another capitulation to restrictive traditional models of living, is for Alice nothing less than a triumph of character and quite simply the bravest thing she could do. A significant worry underpinning her personal insecurities throughout the film is her doubt that she could truly live without a man, an anxiety only equalled by her corresponding fear of being sucked into yet another abusive man’s orbit. Both the bravado of the emotionally unavailable Ben and the reserved, caustic sturdiness of David clearly appeal to her because they in some way echo her late husband’s behaviour, but they are also precisely what scares her. Alice’s decision to leave her Socorro town is one that is surreal, and her plans going forward equally intangible; yet, as she progresses on her journey to find — or, more accurately, actively make — a home for herself, she learns the necessity of making calculated yet unpredictable leaps of faith: she must overcome the initial wariness she holds towards others and take the risk to be welcomed or wounded by the people she finds on her way to stability. By the film’s end, she has found a community that understands her and is willing to help her find her footing within a world she has discovered is just as uncertain about the future as she is. Her final reconciliation with David is an embrace with hope and with the uncertainty inherent to it.

This unconventional, unpopular vision of motherhood as something close to a complete gamble is something Alice adopts from the start, out of necessity, natural temperament, and through tears. Far from the traditional maternal ideal of doting, passive femininity that denotes supposedly “good” mothering, Alice can be crass, short-tempered, and prone to putting herself and her son in dangerous situations. Scorsese’s film reflects the 1970s America in which it was made, when the notion of what it meant to be a good mother was becoming increasingly tenuous as second-wave feminism made its way into everyday discourse. Alice’s self-actualization occurs as she finds strength, but not of the type characterised by the acquiring of masculine-coded traits (strict rules, no place for debate or discussion, and no asking for help, to name a few). Rather, her strength is considerably more rooted in nurturing trust and communication, forgiveness and a safety net of community, in a vision of family life that proves as unconventional as the decade in which it sprung out.

It’s a way of living naturally alive to experimentation and apparent contradictions, qualities that are in the very DNA of Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. Scorsese’s film is profoundly unlike any other precisely because it refuses categorisation. Its thematic juxtapositions are what define its boldness: humour as a means of dealing with grief, mundanity as characteristic of a mid-life crisis, and vulnerability as a core tenet of strength.

The moment it flirts with familiarity, the film skirts away, throttling the viewer into a tone that is neither predictable nor mind-bending, neither sentimental nor cynical, yet wild all the same. Its titular character is, fittingly so, the most difficult aspect of the film to quantify: her toughness is not counteracted with her openness, but woven within it, the two qualities merely opposite sides of the same coin. Here, opposition is not contradiction, but complementary — if such a thesis stammer defies expectation, well, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore wouldn’t have it any other way.