Psycho. #60

Dear Caspar,

I wonder if you could help. The Servant is one of my favourite films, I just love it. Incredible malevolent and camp performances; Pinter's script, Losey's direction and Slocombe’s cinematography are in perfect harmony, it's all so tonally well controlled.

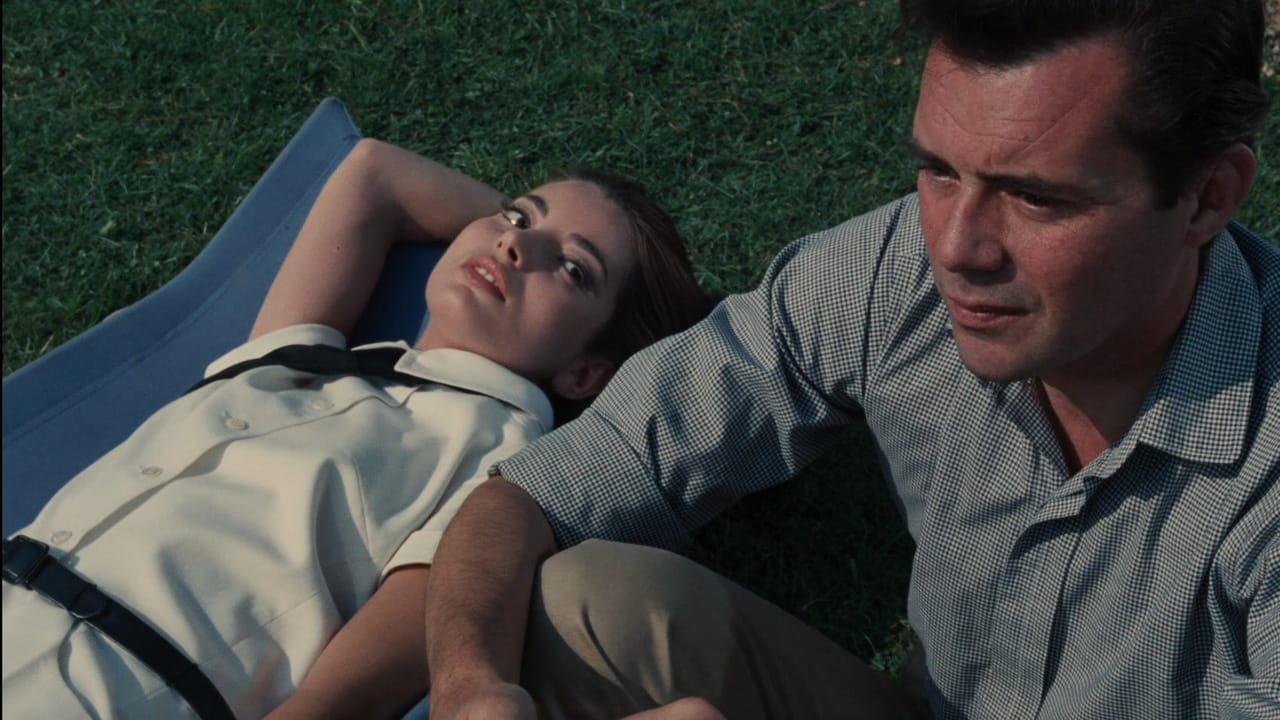

So I assumed that The Go-Between, another Pinter/Losey collab, would be just as great. But I was so disappointed: something about the very wide, tableau-y shots and the frankly hammy acting made me think of things that would be shown on telly in the daytime when you were allowed to stay at home from school with a cold in the 1980s. Or Midsomer Murders. The acting is so uneven. Julie Christie and Alan Bates are fabulous, obviously. The sexual chemistry between them is overpowering, even when they’re not in the same scene. But the children, although endearing, are so wooden. I guess my question is this: what the hell is Losey doing? The tone is so confusing to me, I don’t understand what he’s trying to say. Am I being tin-eared?

PS.: I haven’t watched Accident yet, apparently the third Pinter/Losey collaboration. I’m scared in case I don’t like that either.

How wrong you are! Wrong, wrong, wrong! I do see how, if you were coming to The Go-Between after The Servant, rather than the other way around, you might feel somewhat discombobulated by its apparent bourgeoisie and staidness – but I truly believe the films stem from the same filmic impulse, and that The Go-Between is of a piece with The Servant in its investigation of secrets, lies, class relations and power dynamics of the English. I think that at heart, here, is an appreciation of a film’s means as well as its text.

A note, for readers who aren’t necessarily as versed in the works of Pinter and Losey, on the films in question. The Servant is a 1963 adaptation of a novella by Robin Maugham, homosexual nephew of W Somerset Maugham, another famous English poof of the 20th Century. (I thoroughly recommend a perusal of the private life section of the latter Maugham’s Wikipedia, which is messy in the extreme) The Servant functions very like theatre, being relatively contained in its narrative, and it shares with Pinter’s early work the quality of being extremely tight and casually brutal. Losey’s work, giving form to this narrative, feels attuned to a kind of lightly baroque madness: it’s claustrophobic and off-kilter.

The Go-Between, made eight years later, feels more expansive and classical, because it takes a far more famous novel and explores a totally different time, giving it the appearance of a period piece. Of course, it is officially a period drama, being set in Edwardian times and among the upper classes of the day. But The Go-Between, like The Servant, was crucially written by a homosexual man; and the film of it by Losey (an American exiled to the UK because of his left-wing sympathies) and Pinter (a London-born, lower-middle class Jew who came of age in the between-wars) has a deep understanding of class, and of the painful situation of the interloper at its heart. Losey’s filmmaking, it seems to me, is left-wing and abrasive, finding much the same type of discomfiture as they probed in The Servant.

Losey says so himself, discussing the film’s appeal to an early 1970s audience: “As one man put it, who would be interested in a bit of Edwardian nostalgia? That's idiotic. It is certainly not a romantic or sentimental piece. It has a surface and a coating of romantic melodrama, but it has a bitter core.” The way the British upper classes look after their own and thoughtlessly pulverise lives in their midst that undermine the structure on which their power is based, is heartbreaking to me. And Losey does not miss his mark when skewering these people, he captures all that violence, even though it is couched in etiquette: the film’s denouement is shattering.

So here is the difference: The Servant is insolent and abrasive, mocking and subverting class and power structures; The Go-Between is far more melancholy and defeatist, depicting the interlopers as the great losers in this battle, victims changed for life. Losey knew whereof he spoke. But I really do believe that in their intent and their execution, they are both radical and powerful films. Yes, the acting is uneven – you simply can’t rely on a British child-actor before the 1980s to sound like anything other than a Famous Five automaton – and the film makes a great display of costumes, dinners, a cricket match, a concert. But these are external factors: everywhere else, Losey’s eye is wayward and piquant, finding disconcerting angles and strange tableaux. There is such a strangeness to the film, particularly in the way that Losey and Pinter pick up on the novel’s bizarre themes of black magic: all of this, it seems to me, is quite wonderful. Perhaps these clashing themes, and the brisk approach of Pinter and Losey, do make for a confusing tone, as you say; but I would urge you to look again, with an eye on what is so uncanny about Losey’s filmmaking – and to listen out for the underlying violence as picked out by Pinter.

Another thing you could do would be to watch the BBC’s TV adaptation of Hartley’s novel, from 10 years ago, and draw comparisons with Losey’s take. I watched the TV film way back when, and found it handsomely mounted, faithful to the source material, and perhaps most importantly the kid is good. But if you watch it I bet you will find, as an admirer of The Servant, that this is the actual bourgeois fare, the pleasant Sunday afternoon entertainment that you mention – and that the original film is far more likely to haunt you with its poetics and eeriness.

I would like to add a personal note here, which is to say that when I acted as a teenager I made a film based on a short story by Henry James (also a homosexual), about a young boy from the Victorian upper classes at the turn of the century who comes up against the cruelty and machinations of his family. This, you will note, is roughly the theme of The Go-Between, which is set around the same time as James’s story. The director of the film I made was vocal about taking Death in Venice, by Visconti, and the works of Joseph Losey in general, as points of reference for our film. In the end, I think he was too awed by those filmmakers, and spat out a movie that was too indebted to them, too compromised by its intentions and obviously not capable of those heights. But I remember some shots that he set up, which were off-kilter and dizzying, and the kind of dissonant quality of the clipped dialogue he had written, which had a peculiarly distancing effect. Ultimately, we were seeking to undermine the artifice of the moneyed upper classes, and to reject an obviously cathartic approach; there should have been something weird and dismaying here, in its story of a kid who sees all and gets destroyed by life. I hadn’t seen any Losey then – I felt so recherché even being aware of him as a teenager – but I was quite struck by his three films with Pinter by the time I came to them, later, as a young man. I had appeared in a Pinter play as well, as a child, and so I felt a certain kinship with their work together. I watched the films in this order: Accident, The Go-Between, The Servant, and had you not already watched two of them I would have recommended this order. Accident is an excellent film, but I would need to watch it again to write about it properly. I recall, certainly, that it is perhaps even more distancing than the two films I’ve talked about here; more than either film, it feels a product of its age, perhaps a little dated. But Losey is formally daring here too, and if you can look past the clipped accents and seemingly stagey flavour, I think this is also a radical filmic proposition.

Have you seen The French Lieutenant’s Woman, Pinter’s adaptation of John Fowles, filmed by Karel Reisz? A good film, I think, although no movie can really hope to emulate the book’s richness and postmodern sensibilities. Pinter is formally daring, coming up with a double ending that seeks to capture the book’s two discreet finales, but the narrative framework he has come up with is not entirely successful in that regard. I am surprised in this film by the way that Pinter, by now, is more readily subsuming his own authorial voice into the tone of the film he has come up with; I suppose this is to do with his transition from an angry young man to a member of the establishment. Did Pinter, eventually, fit in? Did Losey? I believe both of them stayed outsiders, that that identity stayed with them forever. Pinter married a Lady, and got a Nobel prize; but even in his acceptance speech, he railed and harangued. That’s a voice that can’t be silenced.

Send your questions anonymously to Caspar at this link, no personal information is collected.