Psycho. #61

"Cinema bros"?

Paul Thomas Anderson belongs in the same ‘cinema bro’ category as Christopher Nolan – both produce thrilling, empty vessel films which masquerade as deep while simultaneously saying nothing. The female equivalent is Sophia Coppola/Greta Gerwig.

Incorrect! This is a truly terrible take from you, whoever you may be, so I propose that we get into it without any further ado. Just before this: how dare you? Are you sick in the head? Have you no shame? Rinse your mouth out with soap! Disgraceful behaviour. Go away somewhere to think about what you’ve done and don’t come back until you’re sorry!

OK, so, now that that’s out of the way, to the business of your statement. When you say that Paul Thomas Anderson belongs in a ‘cinema bro’ category, do you mean that he is a bro, or that his admirers are film bros? If the former, I don’t think you have a leg to stand on (although I will address that shortly); if the latter, you might have half a point. Especially if you consider that Sofia Coppola and Greta Gerwig appeal to a certain audience that greatly estimates their explorations of “the feminine”, by which I mean a predominantly white, predominantly straight, predominantly young femininity. That would make a certain kind of sense, at a push. I do think that “film bros”, such as they are, have a fondness for ‘Nolan’ and his films, which I agree with you are quite empty. And I think that Nolan himself is “bro-y” in the sense that he makes adventure films in a language that is codified as male, with big budgets, star actors, and, crucially, often with a particular filmmaking constraint (the story is going backwards; there’s a twist; it’s set across a week and a day and an hour, or whatever) that appeals to a certain kind of brain that enjoys working things out rather than thinking or feeling.

Diehard Paul Thomas Anderson fans do tend towards the film bro-y, I will grant you: these people like to rank the films, and fetishise the formats upon release, and wear “I drink your milkshake” t-shirts. They love the Boogie Nights one-take in the club but perhaps haven’t reflected much on the little boy abjectly pissing his pants in Magnolia. In other words, those people represent only the tip of the Paul Thomas Anderson appreciation iceberg, and he should not be tarred by association.

Many fans of artists deeply misunderstand or traduce their work: the depressing, tedious cult of The Big Lebowski, with dressing-gown wearing “dudes” drinking White Russians and going bowling, puts the film in the same sort of territory as Dude Where’s My Car, or Bill and Ted. That is a horrific disservice to a brilliant film by the Coen brothers for god’s sake, the guys who made Inside Llewyn Davis and A Serious Man, hello?! The Big Lebowski is – among other things – a political film about the folly of American interventionism, made in the years following the first Iraq war; it is extremely intelligent on language and mimesis, and the way passing culture and politics pollute the everyday. The film bros who quote “Fuck it Donnie, let’s go bowling” at each other ad nauseam are no reflection on the brothers and their work.

Or take Jane Austen, probably the most significantly misunderstood of all writers – the millions of fans worldwide who turn to her for country houses and romance make a mockery of a body of work which is deeply sceptical of the concept of romance, and of a writer who is pragmatic, all-seeing, cruel, audacious, witty and experimental before all else. Still these people head to the Austen house to take tea in the grounds and wear Regency dresses, and quote Lizzie’s rejection of Mr Darcy to each other; and still the publishers issue Austen’s books with covers garlanded in flowers and ribbons; and still filmmakers plunder her oeuvre to turn out romantic comedies avant l’heure that bear scant relation to Austen’s sharp depiction of English society and its vicious niceties.

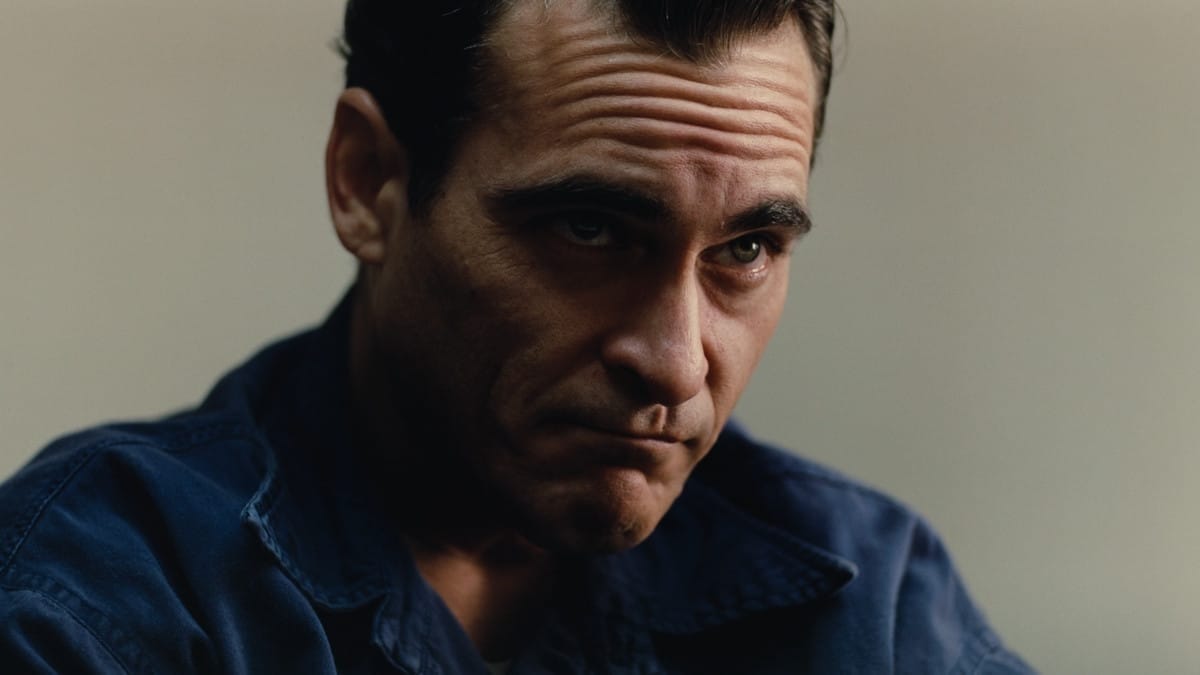

So it is that some PTA fans – the film bros who love There Will Be Blood but, weirdly, aren’t so hot on Phantom Thread – miss the point of his work. Certainly, Anderson is interested in masculinity – but almost all his men are stunted or broken, and entertain relations with one another that are sick and twisted in their power games. I don’t know if I’ve ever seen a protagonist as lost as Freddie Quell, the drifter played so brilliantly by Joaquin Phoenix in The Master (2012): ruined by war, he is prone to bouts of violent rage; he is looking for something, anything, to hold onto – but all he receives is the aggressive one-upmanship and lies of Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman), a father figure who can only betray and abandon him. Towards the end of the film, as Quell is straddled by a sex-worker, his frame so frail, his expression so worn, I felt almost suffocated by his weltschmerz, by the toll his odyssey had taken upon him. This is the masculinity that Paul Thomas Anderson shows us. I don’t consider that bro-y. I don’t find it thrilling. It isn’t empty.

Now – aside from the front-facing ‘text’ of Anderson’s films, which are often preoccupied with men and their travails: is his filmmaking itself “bro-y” (or perhaps macho would be a better word)? I can see how it could be accused of that: certainly there is a degree of showmanship in his work, which occasionally draws attention to itself. I’ll take some examples from The Master, since I’ve started on that: there’s a knockout scene, filmed as a fixed shot, in which Quell destroys a toilet in his cell, while Dodd stands by impassively; or another bravura setpiece in which Dodd goes out riding on his motorbike in the desert, dust billowing behind him. Or what about the astonishing party sequence, where progressively the rest of the invitees become naked as if in a dream? These scenes are dynamite, and I suppose they stand out from the rest of the film – but I don’t think this is grandstanding. I think Anderson uses all the means available to him to paint his characters and their nausea. He is gifted. What we’re seeing is accomplishment.

So it is that in Anderson’s latest, One Battle After Another, I had my breath taken away by a number of astonishing setpieces – especially the chase towards the end, in which Anderson films the road so close you can almost feel the heat from the asphalt on the hairs of your arm. These shots, as they are filmed and edited, produce (as they are intended to) a kind of deep wooziness; but they also provoke wonder, and pleasure. To see something caught so well, and rendered with such aplomb, is a privilege for us as viewers; even better, these shots are worked into the very fabric of the car chase, because the scene’s conclusion relies fundamentally on an understanding of this terrain. Car chases on their own don’t interest me, and usually I think of them as an exercise in machismo: a nonsensical formula set in a false-real world where super-men get in their private vehicles and cause a lot of mayhem while staging a protracted cockfight. But I genuinely do think PTA is doing something new with it here: the scene is so freighted with fear, and filmed at such nerve-wrackingly close quarters, and its outcome so flatly simple and ingenious, that it outstrips the Ronins and Bournes that came before. (I still have a lot of time for the delightful car chase in What’s Up, Doc? (Peter Bogdanovich, 1972))

I just don’t understand how a person could consider Phantom Thread “empty”, or what in it might be termed “thrilling” in the commonly understood sense of the word. I know that two shots in the film made me tingle all over: one, a needle bursting through stiff cotton with a pop, and the other a shot of eggs cooking in a pan, all buttery and yellow. That could hardly be called bro-y. And what of the film’s language, its gorgeous understanding of English class; its strange and maddening fairytale register; the witty observation of routine, heightened by PTA’s exquisite eye for detail, mirroring his main character’s perfectionism; and the elegant, ardent, mysterious performances that Anderson coaxes out of his leads? A shot where Reynolds Woodcock briefly, so briefly, sees his dead mother sitting quietly on a chair in his room: that speaks of a man whose relationship to women has been dictated by his love for his mother; it is perfectly, perfectly weighted, in its length and its framing, to summon a burst of empathy for this waspish, cruel man.

One Battle After Another is a different object altogether, but I would think twice before calling it empty, or bro-y. For one thing, women ground the action of the film, especially in its sizzling first third. For another, there is too much care here, too much meticulous craft in the execution of this tale. You could argue that Teyana Taylor’s character is objectified, as a woman of colour; I think this is a weakness in the film, and yet I also see how Taylor grabs hold of the film, and Anderson allows her to cast a spell over it. I can see the case that there is a race problem here – but even then, I think that isn’t for want of trying to get it right. In one wonderful aside, Di Caprio’s character says, of his daughter: “I don’t know how to do her hair.” Paul Thomas Anderson’s children are mixed race, and I think that in writing that line for his star he gave us a simple, perfectly poignant moment describing his character’s unease, and all his love, in one fell swoop. That is the writing of a man who has a heart. Is One Battle After Another rather more occupied with a kind of action-y cinema, a more mainstream sort of aesthetic than I usually prefer from him? Absolutely. But even so there is heaps to see, hear, revel in: a peerless ear for music; a camera that always finds the right vantage point; a father and daughter scene filmed just so, in an empty chapel; and characters who are coloured in with rich humanity right down to tertiary actors. For all these things, I’m thankful.

I wouldn’t insult Paul Thomas Anderson by comparing these gifts, these delicacies, with the confected games and nonsense of Christopher Nolan, but I think it should go without saying that Tenet or Dunkirk, whatever their technical feats may be (I don’t like either film), are simply not of the same order as the films discussed here. One director is an entertainer; the other an artist. If, in principle, I’m with you in the impulse to shoot down critical darlings, I think this isn’t the lens through which to do it. But thank you for the polemic, bro!

Send your questions anonymously to Caspar at this link, no personal information is collected.