The Invisible Michael Jordan

Why sports films eschew sports

I. The interplay of hindsight and self-evidence in Air

Air (2023), Ben Affleck’s directorial venture depicting the behind-the-scenes efforts by Nike to sign Michael Jordan, features little of the basketball star himself. For starters, Jordan is portrayed by a body double only seen in side profile or from behind. In an interview before the film’s release, Affleck argued that Jordan was too big a celebrity to be inhabited by an actor, and that any casting decision would have seemed “fake” to the audience.

But there is another aspect to Jordan which the viewer sees or hears very little of: that of Jordan, the basketball player. The film features only one (near) contemporaneous clip of the athlete, taken from the 1983 National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Finals game clincher for the University of North Carolina (UNC). This relative lack appears to be in line with the main purpose of the film: as critic Adam Nayman points out in his review, Air aims to show “that an essentially faceless corporation found a way to humanise itself through a perfectly chosen surrogate superhero, and that the middle-aged dudes who made the pick were visionaries – cool rocking daddies in the U.S.A.” The film’s thrust, then, isn’t to capture the brilliance of Jordan, but to shed light on those who saw potential in him. It’s in this context that Nayman calls Sonny Vaccaro and Phil Knight, respectively Nike’s chief basketball scout and founder (played by Matt Damon and Ben Affleck), “visionaries”.

And it is to that end that Air establishes, right from the get-go, the underdog status of Nike in the basketball sneaker market. While Converse sponsored basketball stars such as Larry Bird and Magic Johnson, and Adidas was gaining currency among upcoming athletes and the hip-hop community, Nike was considered the boring company associated with running. Before the time period covered in Air, Nike had hitherto done little to change this state of affairs. Marked by inertia, their strategy towards basketball brand building was best exemplified by Nike’s outlay for basketball sponsorships: $250,000 to sign three to four rookies, while their rivals were shelling the same amount for a single player. Furthermore, Nike’s basketball division was in danger of being shut down after the company had suffered losses the previous financial year. With his job on the line, Vaccaro needed to urgently change course. Allocating meagre funds to not-yet-established players would no longer cut it – he had to either go hard or go home.

Two complimentary challenges stared at Vaccaro. He first had to identify the player who would convince Nike to change their strategy, and secondly, he had to persuade the concerned player to sign for the company. The latter was a task in itself, if one is to go by David Falk (Chris Messina), Michael Jordan’s agent: “World Class players do not wear third-rate shoes.”

The player identified by Sonny Vaccaro to change Nike’s fortunes was Michael Jordan, a shooting guard from the University of North Carolina and the third pick in the 1984 draft. Signing Jordan wouldn’t merely be about allocating all of Nike’s funds to him, however. After all, competitors could make similar if not better offers. What was needed was a change in the pattern of endorsements, one in which a player does not endorse a standardised brand but in which the brand is centred around the image, likeness and characteristics of the player. Like Vaccaro states, “The shoe is just a shoe until someone [in this case Jordan] steps into it.” It is precisely this pivot towards a player-centric brand model that wins the Jordans over and secures his signature.

While the reasons for Jordan signing with Nike seem clear enough – they were not only willing to pay Jordan the going rate for endorsements, but also to create an entire brand around him – the reasons for Nike changing their entire strategy around a rookie are less clear.

The method Air uses to justify Nike’s decision, all the while avoiding the nitty-gritty of how the brand came into being, is to anachronistically project Jordan’s future successes onto the past, lending them an aura of prophecy. Perhaps the most poignant case of ‘prophetic exposition’ in the film occurs when Michael Jordan’s mother (Viola Davis) calls Sonny Vaccaro to inform him that her son will sign with Nike on one condition: that he get a share of the revenue from the Air Jordan brand. When Vaccaro tells her that this is an unprecedented demand to make towards a public company liable to shareholders, she responds by stating that her son will be better than the best – that Nike that would benefit from Jordan’s likeness more than he would from the endorsement.

Every single one of the prospective achievements she lists off eventually materialises in history. Michael Jordan ends up winning the Rookie of the Year Award, upstaging the Number 1 pick and future Hall of Famer, Hakeem Olajuwon. He wins multiple NBA Championships and Finals MVPs, is selected several times to the All-Star Game, and wins the Defensive Player of the Year, alongside accomplishing many other historic feats. The specific and matter-of-fact nature of her faith compels Vaccaro to accede to her demand.

Whether such a prophetic conversation ever took place isn’t the main issue with Air. Deloris Jordan may well have envisaged her son becoming one of the greatest – if not the best – basketball player of all time. The problem lies in the film’s failure to meaningfully evoke Michael Jordan’s actual talent. Rather than bring Jordan’s playing style and college career to the fore in order to show what Nike saw in him in 1984, Air rides on the coat-tails of hindsight to tell the viewer how the creation of the Air Jordan brand was an inevitability, thereby leaving little scope for the visionary claims Nayman refers to.

Air’s dependence on prior knowledge may also be due to the impact of The Last Dance, a celebrated documentary on the 1997-98 Chicago Bulls season which was released three years before Affleck’s film. The ten-part series chronicles what would turn out to be Michael Jordan’s last season as a Bulls player by juxtaposing present-day interviews and clips from famous Bulls moments of seasons past, with behind-the-scenes footage shot by NBA Entertainment during that season.

Initially set for release in the summer of 2020, the show was moved forward to April following the sudden onset of the COVID pandemic. In an environment bereft of live sports, The Last Dance served as succour to sports fans, but also to the media landscape itself. The series assumed such relevance that events documented in the show were discussed and (re)litigated as if they were happening in contemporary times. Podcasts, TV shows, and articles pored over Jordan’s historical greatness, the perks and pitfalls of celebrity, and the nature of the game in the 1990s. Debates even entered the realm of the hypothetical, with shows speculating on how Jordan and the Bulls’ style of play would have translated in the present NBA era.

Jason Hehir, the director of The Last Dance, claimed in an interview that apart from narrating the story of Jordan and the Bulls’ dynasty, the documentary on a larger scale is also about the pursuit and price of greatness. The series did become a springboard to discuss sporting excellence in general, and the excellence of the Bulls and Jordan in particular, reviving the Greatest of All Time (GOAT) Debate – which Air participates in through its final montage.

II. The Last Dance and its use of highlights

Highlights – compilations of sporting events that showcase key moments in a match or of a player’s career – are essentially acts of abstraction. While they are useful conversation starters and help give the viewer the bare bones of what transpired, they remain technological reproductions that dissipate the aura of the original performance, much like replicas of famous paintings. [1] Highlights form the backbone of most sport documentaries, but their efficacy in approximating the reality of the original performance depends largely on the narrative structure they are embedded in.

The pitfalls of a poorly contextualised highlights package are best exemplified by a trend in NBA Twitter circles, wherein two-minute compilations of players’ career highlights are prefaced with the title “X was a problem.” These clips have been subject to ridicule because of their tendency to showcase certain moments of a player’s career without any further context about the player or the moment at hand, thereby unwittingly equalising different players and their talents in a continuum of slick moves and skills.

The Last Dance likewise relies heavily on highlights to buttress its arguments about the greatness of Jordan and the Bulls dynasty. And much like the two-minute reels mocked on Twitter, these compilations fail to provide the requisite context to justify the claims made in the documentary.

To elaborate on this further, it is useful to return to the circumstances that made The Last Dance possible. As previously mentioned, NBA Entertainment were granted access to the Bulls’ dressing room for the 97-98 season precisely because this was to be the last season of a vaunted team. The imminent dismantling of a team that won 5 of the last 7 NBA titles wasn’t due to ‘natural’ reasons, such as the retirement of key players or injuries. Rather, it was a decision imposed by management and ownership, who felt that it was time to ‘rebuild’ the team. Considering the orchestrated nature of the demise of the Bulls’ sporting dynasty, the team, led by coach Phil Jackson, decided to coin this season their ‘Last Dance’ together.

Yet, unless the viewer has prior knowledge of the NBA’s history, it is difficult to put the magnitude of the Bulls’ achievements into perspective, let alone comprehend the travesty of ending the Bulls’ championship window in such a manner. For instance, we learn little in the documentary about what constitutes a dynasty in NBA terms, nor do we realise what differentiated Jordan from the other greats of the game.

One is left with a narrative in which opponents and teammates alike simply shower praise on Jordan. Larry Bird, the legendary Boston Celtics small forward, describes him as “God disguised as Michael Jordan”, and Reggie Miller, one of the greatest three-point shooters in the game’s history, refers to him as “Black Jesus” – incidentally a name Jordan uses to call himself. These quotes are interlaced with highlights from signature Michael Jordan performances, like in Air, yet neither the film nor the TV series can describe Jordan’s greatness in sporting terms. Instead, a set of clips is interlaced with self-evident statements from Jordan’s peers about his greatness, establishing Jordan and the Bulls as Problems par excellence.

III. The RewatchaBulls: How Jordan’s Aura was (re)captured by a podcast series

Among the programmes and shows that appeared in the wake of The Last Dance and in a sports media landscape deprived of live sports during the COVID pandemic was the ‘RewatchaBulls’, featuring Bill Simmons and Ryen Russillo. Taking its inspiration from the Ringer podcast series named The Rewatchables, the podcast sees its hosts rewatch pivotal basketball games in Jordan’s career like one would rewatch a film.

Prefacing the launch of this series, Simmons explained that although The Last Dance was a 10-hour documentary, there remained some “real basketball nerd stuff that we can have fun with here”. Over the span of seven episodes, Simmons and Russillo use the occasion of The Last Dance to paint a vibrant picture of some of the games that made Jordan the legend that he is.

While both The Last Dance and The RewatchaBulls recap famous moments in Jordan’s career, they differ in their engagement with hindsight and historical knowledge. The Last Dance rushes from one moment to another, eager to reach the climatic point of Jordan and the Bulls’ 6th NBA title in their ‘Last Dance’ season. The RewatchaBulls, by contrast, performs a delicate dance between present-day information and the historical moment at hand, bringing out the tension and stakes of crucial games in Jordan’s career.

An example highlighting this contrast between the two formats is the episode covering the 1997 NBA finals between the Chicago Bulls and the Utah Jazz, which included the iconic Game 5, popularly known as the Jordan Flu/Food Poisoning game. In The Last Dance, Jordan’s Game 5 performance is seen as another instance of his tenacity and never-say-die approach. After the Bulls’ victory in Game 5, the series shows a clip of a post-match press conference featuring the Utah Jazz head coach, Jerry Sloan, who tells reporters that he had no idea Jordan was severely ill during the game.

While this crucial piece of information is brushed over and not dwelled upon in the Netflix series, it becomes an important talking point in the RewatchaBulls. The podcast sets the context of the 1997 finals by impressing that even though the Bulls had a superlative regular season (the joint third best of all time till date), they were not considered to be playing to their utmost potential. Moreover, the Jazz arguably had a more versatile and deeper roster than the Bulls heading into the finals. In short, the result of the finals could have gone either way, especially considering Jordan’s illness on the eve of the game. Taking these aspects into account, the failure to exploit Jordan’s illness by the Utah Jazz assumes even more relevance, and is perhaps the turning point in the series.

Besides an in-depth look at the tactical battles in these games, the podcast also provides us with a better glimpse of the NBA landscape during the 90s. A pertinent example is how the addition of six new NBA teams in the 1996-97 season led to a dilution of talent within the league, which contributed to some extent to the Bulls’ record breaking 72-10 run in the regular season. A running theme across the podcast is an analysis of the various announcers who provided commentary for these games. Marv Albert for instance, is almost inexplicably never impressed with Jordan’s feats, while Bill Walton consistently implores the Utah Jazz power forward, Karl Malone, to use his size and take shots near the rim rather than settle for jump shots. Not only do these examples highlight the biases and stylistic preferences of the announcers in question, they also provide a glimpse of the NBA media in the 90s.

The Last Dance, on the other hand, and despite its vast repository of highlights packages and behind-the-scenes footage, is unable to provide a riveting picture of the times. What remains is the now famous meme, wherein Jordan is seen gesticulating his hands with the caption “... and I took that personally”, representative of the overarching (and perhaps only) theory of the show – wherein Jordan, and by extension the Bulls, excel whenever the star player takes things personally, whether that’s being snubbed for year-end awards or facing trash-talk from his competitors.

IV. The ghost of David Halberstam: A key to understanding Jordan’s greatness

Although Simmons and Russillo take pains to bring back some of the tension inherent in the many match-ups featuring Jordan, they also assume that the listener is familiar with what made Jordan special, since their podcast is in conversation with The Last Dance. Another reason for this assumption is that Simmons has written one of the definitive books on the NBA, The Book of Basketball, wherein he not only charts the course of the league’s history, but also ranks the greatest NBA players of all time, with Michael Jordan unsurprisingly ending up at the very top of the list.

However, another book helps better unpack Jordan’s legend: David Halberstam’s Playing For Keeps: Michael Jordan and the World He Made. Published in 1999, Halberstam’s book is considered one of the primary works on Jordan’s life and career, but crucially, it is also the origin of the aforementioned structure employed in The Last Dance – a contribution which shockingly isn’t acknowledged by the show's makers.

A Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, Halberstam got access to the Bulls locker room in the 97-98 season much like NBA Entertainment, and was able to secure interviews with nearly all the major figures that were part of the Bulls’ journey, bar Jordan and Scottie Pippen (small forward and the only player besides Jordan to be a part of all six title-winning teams for the Bulls). Many if not all of the incidents covered in The Last Dance find mention in Halberstam’s book, but are covered from a different perspective. Unlike the series, Halberstam’s goal was not to retell a self-evident story of Michael Jordan’s greatness, but to decipher it in journalistic fashion.

An example to illustrate this difference is in how the two works retell Jordan’s record-breaking 63 point performance against the Celtics in 1986. Jordan’s showing still holds the record for the most points scored in a playoff game. This is the performance commemorated by Larry Bird, in his famous words about “God disguised as Michael Jordan.”

In The Last Dance, this game is presented as an instance that exemplifies Jordan’s talents while foreshadowing the great achievements that were to come. However, rather than dwell on the magnitude of this event, the show sees it as yet another example of how the player took things “personally”, in this case after being motivated by trash-talk from the Celtics guard, Danny Ainge.

In Playing for Keeps, by contrast, the monumental nature of Jordan’s performance is brought into full relief, which in turn helps unlock the secret to his greatness. Halberstam begins by describing the legendary nature of Jordan’s opposition, which featured one of the most formidable frontcourts of all time consisting of Larry Bird, Kevin McHale and Robert Parish.[2] Added to this legendary trio was the sixth man, Bill Walton, a former MVP and NBA Champion himself, who was one of the best centres in the league during his prime.[3]

Jordan’s ability to consistently penetrate this storied front court, even though he himself was a relatively short player standing at 6 '6, is precisely what made his feat merit such extraordinary praise from a competitor who had already etched his place in the pantheon of basketball greatness. The following excerpt from the book captures the magnitude of Jordan’s talents and his showing against the Celtics in the technical terms it demands:

Generally, if you were a big man playing defense, it was possible to gauge the great offensive players coming at you, to know their moves and to understand the angles they were coming from and the limits of their reaches. Yet here was this young player who seemed to defy those normal limits [...], floating by you as if with an extra gear. You thought you had his trajectory mapped out, and then he extended it. Or you thought you had his plan of attack charted, and then once in the air he switched the ball from one hand to another. It was a dazzling display.[4]

In Halberstam’s analysis, Jordan's showing against the Celtics was not just another great performance against a dominant team, but a window into a new prototype of player – one who could challenge the rim with his athleticism and dribbling skills, as well as score with jump shots from the perimeter. In a league that was hitherto dominated by centres, here was a shooting guard who would inspire a legion of players and usher in an era of perimeter play.

It is in this context that the words of Sonny Vaccaro in Air, about wanting to “fly” after seeing Jordan, actually make sense. In a game that was traditionally characterised by tall players who would pound the ball near the basket, here emerges a phenomenon who “flew” to the basket, thus gaining the moniker, Air Jordan.[5]

V. The History of the Victors and A History of the Vanquished: A theoretical excursion with Reinhart Koselleck

In his essay "Transformations of Experience and Methodological Change", the conceptual and intellectual historian Reinhart Koselleck unpacks how the twin meanings of the term ‘history’ influence the way it is experienced and written over time. Koselleck points out that ‘history’ means both the study of the past, and the past itself; in other words, it always carries the twin imports of signifying both historical experience, and historical method.[6] Koselleck goes on to chart the “formal features” common to both historical experience (immediate, generational, and long term) and historical methodology (the recording, continuing, and rewriting of history). In his view, these features not only provide unity to the practice of history, but also indicate that historical experience cannot be apprehended without historical method/writing.

The concluding section of his essay consists of another formal hypothesis. Titled "The History of the Victors - A History of the Vanquished", it counters the famous dictum that history is written by the winners. Koselleck, with his statement, does not claim that the victors do not write their accounts of history. Rather, he argues that the History of the Victor “has a short term perspective and is focused on a series of events that, through their own efforts, brought them victory.”

He contrasts the History of the Victor with that of the Vanquished, who, unlike the former, are intent on studying the long term causes of their failure. The singular experience of having failed gives the vanquished the tools and desire to seek different answers from history, thereby bringing methodological innovations in the discipline.

Koselleck makes a convincing case that many key theorists of historical method belonged to the side of the loser. Thucydides was a failed military commander; Machiavelli, an exile; and Marx, a fugitive. The example of Thucydides helps elaborate this hypothesis. A commander for Athens in the Peloponnesian war, Thucydides had arrived late to the battlefield and as a result was banished. In Koselleck’s view, seeing the battle from a distance enforced by banishment helped Thucydides to not only see the event from the perspective of all participants, but also to recognise the long term causes for the war, beyond the actions and intentions of the immediate participants.

Air and The Last Dance serve as histories of the victors – narratives in which viewers are all but told to marvel at the charisma of protagonists who went on to achieve unprecedented success in their respective fields, without ever venturing into the circumstances at hand and qualities involved in reaching those goals.

VI. Dorktown: A Koselleckian riposte to conventional sports documentaries

In a documentary ecosystem obsessed with winners, Jon Bois and Alex Rubenstein ask the opposite questions. What if one chronicled the history of sporting failure? How would a study of failure inform one’s ideas about sports? And more importantly, as Koselleck posits, what would the form and structure of such a history be?

Through their series, Dorktown, uploaded to their YouTube channel, Bois and co. seek to investigate this theme by narrating the history of some of the most dysfunctional franchises in American sports, such as the Atlanta Falcons and the Seattle Mariners. In The People You're Paying to Be in Shorts, Bois and Rubenstein alongside Seth Rosenthal and Kofie Yeboah look at the 2011-12 NBA season of the Charlotte Bobcats (now Hornets). If failure is a benchmark for Bois and co, the Bobcats aced all the charts, ending with the worst ever single season record in NBA history to date. What makes the Bobcats’ story even more interesting is that they were owned by Michael Jordan, the basketball player perhaps most strongly associated with success.

People... can be read as a companion piece to The Last Dance: both tell the story of a team’s NBA season, and in both, the shadow of Michael Jordan looms large. Yet due to the diametrically opposite nature of the story it tells, People... is also an antithesis to The Last Dance in particular, and to sports documentaries in general.

The narration of sporting failure necessitates a different approach compared to conventional sports documentaries. Interviews and access to those involved are difficult to come by. Historical excavation, rather than journalistic inquiry, therefore becomes the preferred mode of storytelling. Dorktown documentaries see these limitations on access as opportunities to tell stories in new ways, piecing together a wide range of archival sources through the twin methods of voiceover and animation.

The animations used in these films are themselves of an atypical nature. Creatively bringing statistics into conversations with one another, they showcase the possibility of storytelling through numbers. People…, for example, shows that Charlotte’s historically poor NBA season wasn’t just a function of inept performances or a sub-standard roster, but also due to historic power dynamics within the NBA.

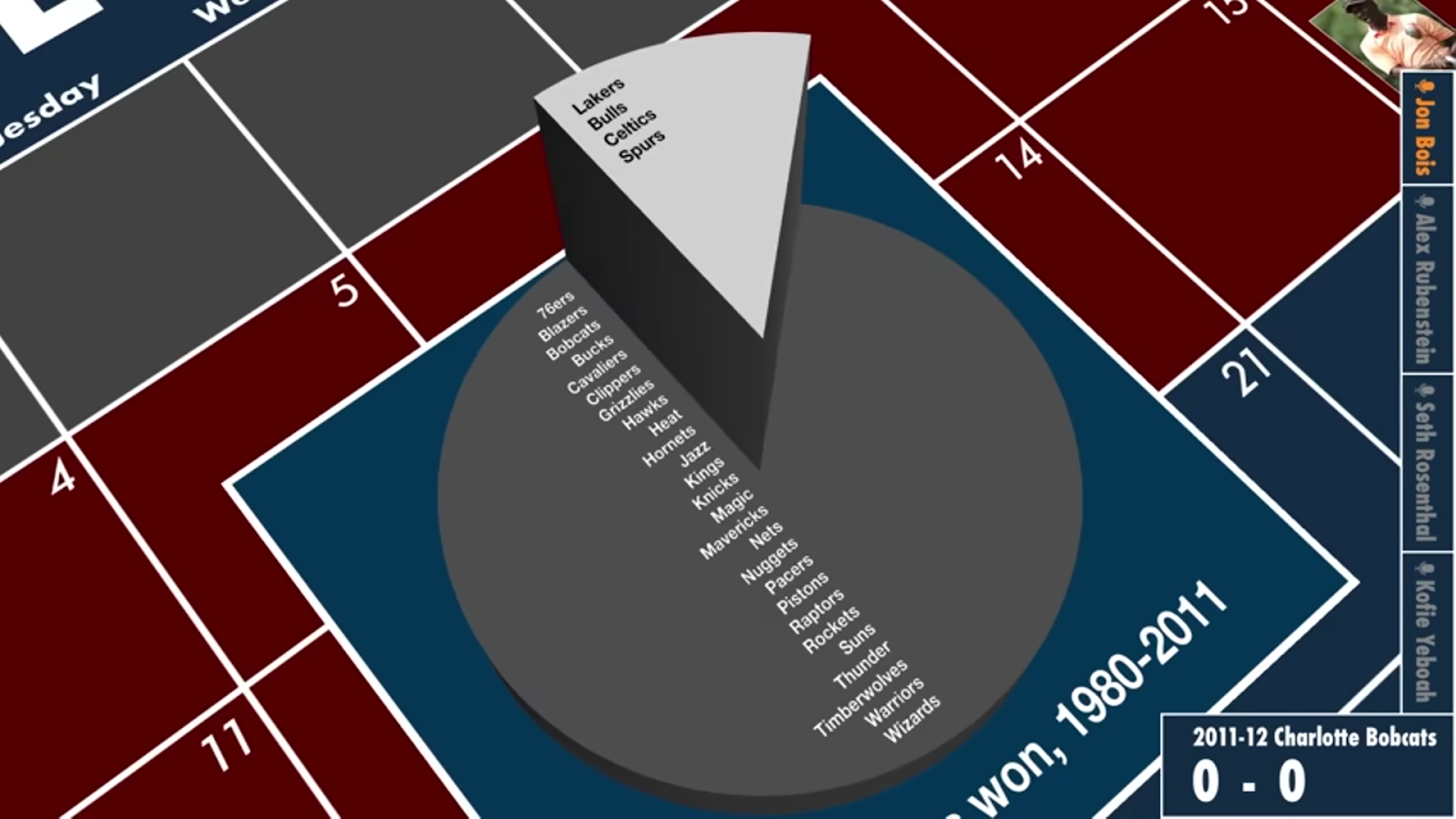

The film points out that, out of the 32 NBA championships won between 1980-2011, 24 (or 75 percent) of the titles were won by four teams – namely, the Boston Celtics, the Los Angeles Lakers, the San Antonio Spurs, and the Chicago Bulls. In his voiceover narration, Bois points out that in such a skewed state of affairs, most teams know even before the season begins that they have no shot at competing, let alone winning a title.

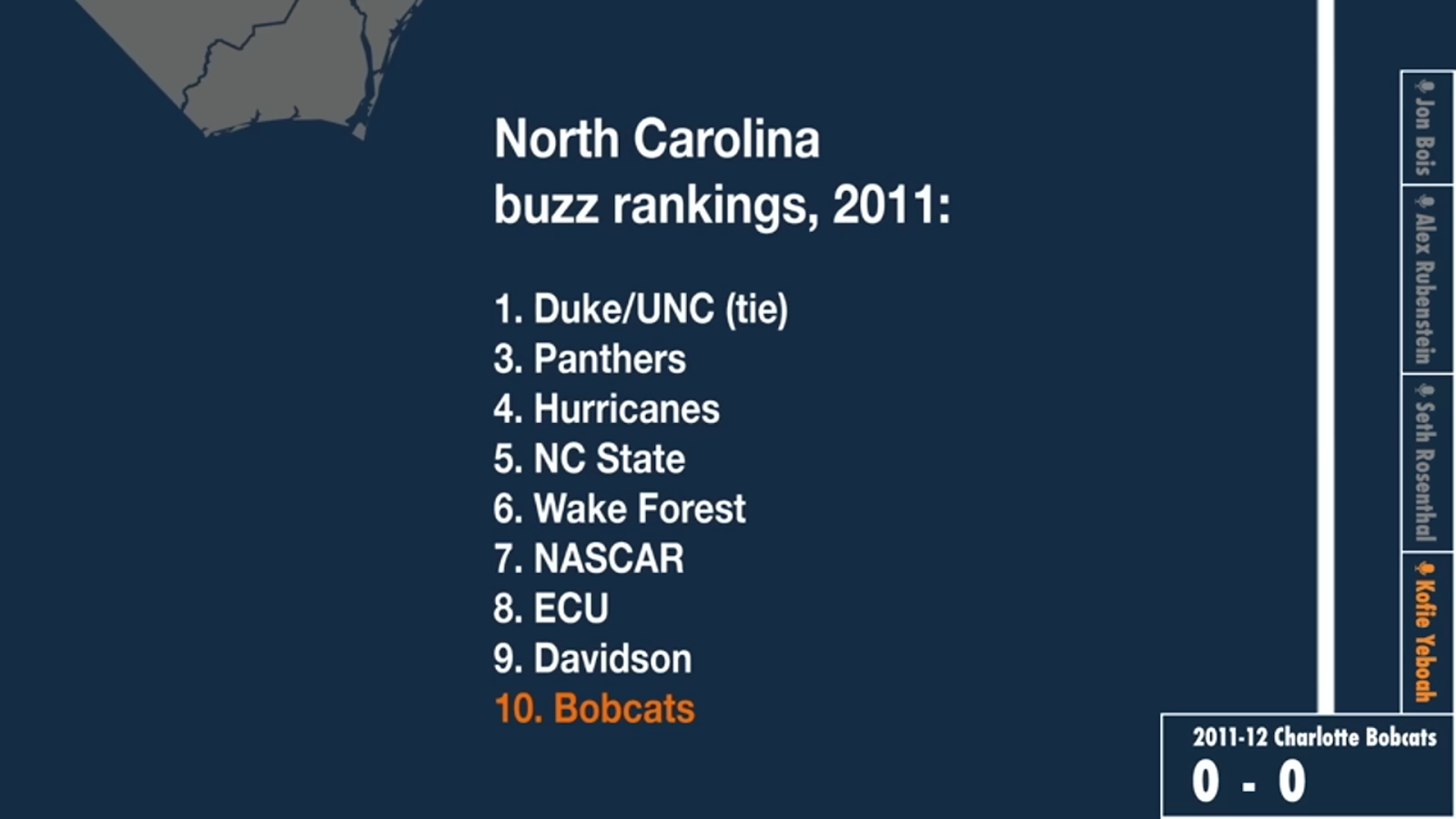

Further compounding the misery of the Charlotte Bobcats was the fact that NBA basketball ranked extremely low at the time in the totem pole of sports fandom in North Carolina – a state with a revered history of college basketball and professional football among other sports. This lack of status kept fans and prominent free agents away from the Time Warner Cable Arena.

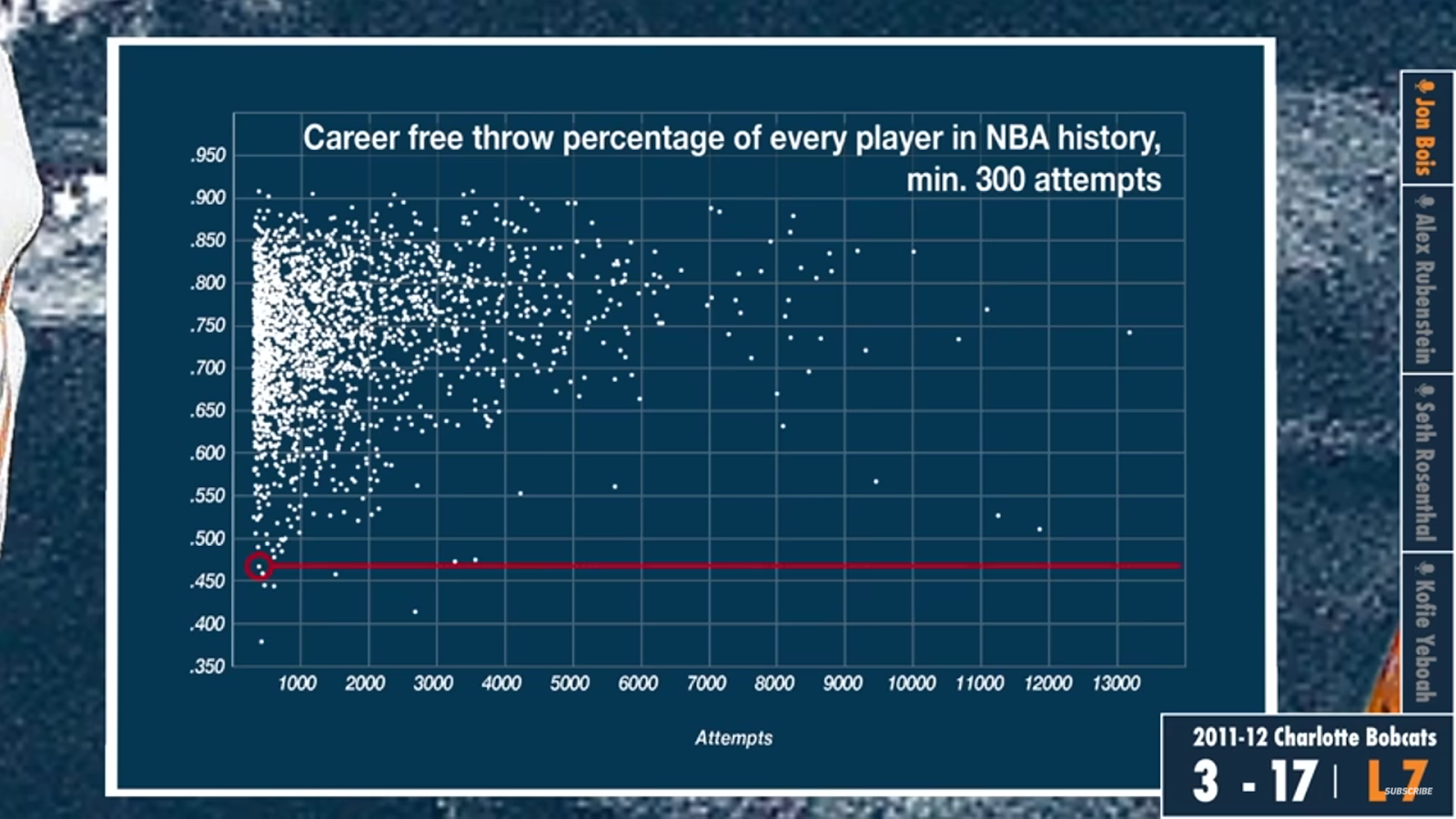

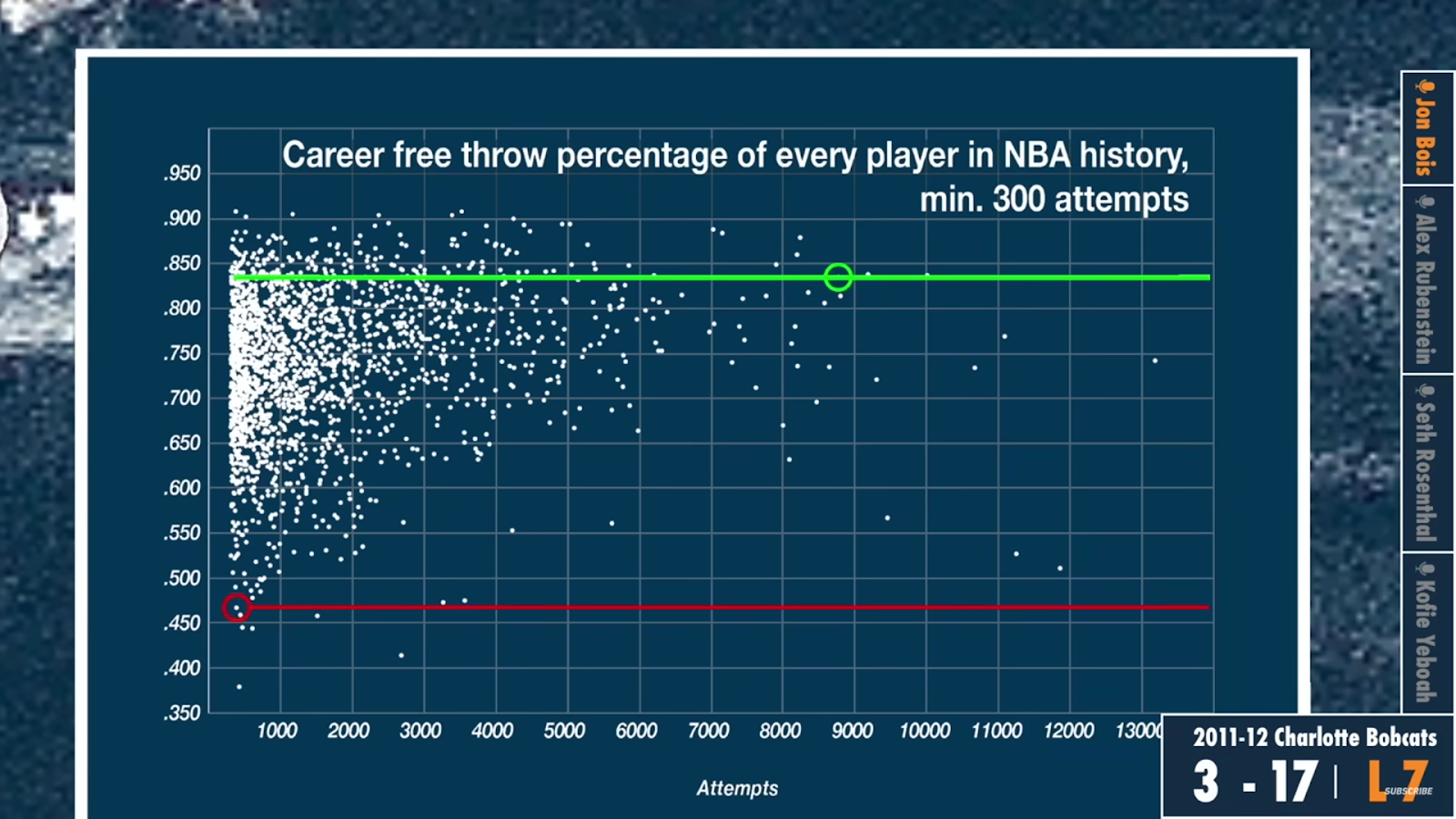

Perhaps the most poignant use of stats in the film involves the playing career of Michael Jordan himself. The Bobcats begin the season with a record of three wins and 17 losses and are facing fellow strugglers Washington Wizards in a crucial match. In the third quarter of a close game, DeSagana Diop, the Bobcats centre, is shown taking a free throw. At this juncture, the film cuts to Diop’s career free throw shooting record – one of the worst in NBA history. The film moves back to Diop taking the shot only to interrupt the highlights again and return to the same graphic, this time highlighting the great record of Bobcats owner Michael Jordan at making free throws. The documentary further adds that, on many occasions, Jordan made these free throws with his eyes closed. After positing the enormous gap between Jordan and Diop’s abilities, the documentary goes back to Diop taking his free throw, one that he misses as the Bobcats slump to another defeat.

It is crucial to note here that although the film has many such moments of hilarious juxtaposition between the performance of the Bobcats and the career of Jordan, People… fundamentally isn’t a ‘takedown’ of sporting failure, the way many talk shows on Fox and ESPN are. The 2011-12 Charlotte Bobcats were and remain the worst performing team in NBA history, but that does not make them an object of ridicule in the eyes of Bois and co. Notwithstanding DeSagana Diop’s poor free throw record, his story by most measures is one of success. The documentary tells us that Diop picked up basketball at the age of 16 in Senegal and, after two high school seasons in America, was drafted in the NBA as a 19-year-old in 2001. Diop’s solid defensive play led to a 12-year career in the NBA – well over twice as long as an average NBA career.

An unbalanced roster, sustained bad luck in the NBA draft, injuries to key players, and Charlotte’s small market status weren’t the only factors that led to the Bobcats’ 7-59 record. The 2011-12 season saw a delayed start due to a standoff between players and owners over their respective share of Basketball-Related Income (BRI). Until the previous year, players had commanded a share of 57 percent of BRI — a sum that owners were intent on reducing to around 50 percent. Leading the bargain from the owners’ side was Michael Jordan, arguing that small market teams like Charlotte needed a larger share of the income in order to be competitive in a league that favoured teams in big cities like Boston or Los Angeles.

Jordan’s steadfast refusal to budge eventually led to a new Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA) which reduced the players’ share of income to 51.15 percent – but as things would pan out, this standoff would eventually affect Jordan’s team the most. With negotiations between owners and players taking time, the 2011-12 season was truncated from the customary 82 game schedule to a packed 66 game schedule — one the Bobcats’ roster was unable to adjust to as they stumbled from defeat to defeat. The lack of recovery time between games may have been a factor in the many injuries that the roster suffered during the course of the season; in any case, it certainly didn’t help.

Jordan’s hard-nosed approach as an owner was at a far remove from his days in a Bulls uniform, when he stood up for the rights of players versus the organisation. He nevertheless sustained the belief that a team’s fortunes rose and fell with its players well into retirement, reiterating the sentiment in his Hall of Fame Induction speech while referring to Jerry Krause, the Bulls general manager. The following excerpt from the speech illustrates Jordan’s position clearly:

He (Jerry Krause) said “organisations win championships”. I said “I didn’t see organisations playing with the Flu in Utah. I didn’t see them playing with a bad ankle.” Granted, I think organisations put together teams, but at the end of the day, the team has to go out and play. You know, so in essence, I think the players win the championship, and the organisation has something to do with it – don’t get me wrong. But don’t try to put the organisation above the players, because at the end of the day the players still got to go out there and perform. You guys gotta pay us, but I still gotta go out and play.

Bois and co. do not take this apparent contradiction in Jordan’s positions as an opportunity to merely point out his hypocrisy. While juxtaposing the contradictory stances of Jordan as a player and an owner, they also put Jordan’s unique position as an owner into perspective. Jordan is unlike most of the tycoons who own NBA teams, because we know exactly how he made his money: by giving it his all on the basketball court for seasons on end. This makes his stance on BRI more understandable and worthy of grace in the documentarian’s eyes.

Because People… tells its story from the position of the vanquished, it displays tenderness and empathy for those involved in the unfortunate Bobcats’ season. On the other hand, The Last Dance reduces its characters to obstacles and supporting characters in the grand story of Michael Jordan. Jordan’s opponents are defined merely by their failure, with the likes of Charles Barkley, Clyde Drexler and Karl Malone among others relegated to footnotes in the service of building Jordan’s legend.

VII. Epilogue: How the history of the vanquished permeates the victor’s narrative

Besides Jordan’s preternatural ability as a player, what set him apart according to The Last Dance was his tendency to harness the specific and “limited” traits of his teammates to attain the ultimate goal of an NBA title. And so, while the documentary presents Jordan’s skill as self-evident and not requiring elucidation, the strengths and weaknesses of his teammates are analysed in more detail – precisely to amplify Jordan’s leadership skills. Traces of sporting analysis emerge, for example, when Dennis Rodman’s all-time great skills at defending and rebounding are counterposed to his tendency to court controversy and miss practice.

Scottie Pippen, the proverbial Robin to Jordan’s Batman, is given a similar treatment. Pippen’s abilities as an excellent perimeter defender and athletic ball handler are contrasted with moments in which he wasn’t the ideal team player. One such episode is when Pippen chooses to undergo back surgery during the 97-98 season rather than the preceding off-season out of spite with management over a grossly undervalued contract that was never subject to renegotiation.

The series tells us about the positive traits of these players only to contrast them with their flaws – flaws which Jordan learns to work with in the pursuit of greatness. Jordan’s game, on the other hand, is never discussed, since he could do it all. His personality traits, such as his tendency to set, expect, and enforce high standards from his teammates, even to the point of bullying, are portrayed as a necessary evil to achieve the greatest of heights in competitive sports. His weaknesses are his strengths, much like those interview jokes where candidates tell that their weakness is that they work too hard or care too much.

Yet if one were to watch The Last Dance alongside People…, one could also gauge traces of failure and actual weakness within Jordan’s portrayal. The Last Dance’s determined choice to focus on the past without ever bringing the present to the fore perhaps indicates a reluctance to come to terms with Jordan’s failure as an owner – one it cannot broach due to the very nature of the history it seeks to convey. Jordan eventually went on to sell the Charlotte Hornets (previously Bobcats) for a sum of $3 Billion in August 2023.

Endnotes

1. Here, the term 'aura' is used in reference to the way Walter Benjamin differentiates an original artwork from its mechanical reproduction by the specific time and space the original artwork is situated in, which in turn lends it an aura that the replica cannot recreate. Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), 217-251.

2. In basketball, the frontcourt refers to the zone near the rim. Small forward, power forward, and centre are the three traditional frontcourt positions and are tasked with protecting the rim and making it difficult for opposition players to penetrate the paint (the area most adjacent to the basket).

3. There are five conventional basketballing positions which are determined typically by the height of the player. The centre is usually the tallest player in the team, while shooting and point guards are generally shorter players who operate at a distance from the basket around the perimeter.

4. David Halberstam, Playing for Keeps: Michael Jordan and the World He Made (New York: Open Road Integrated Media), 234-35.

5. This is not to argue that Michael Jordan was the pioneer of relatively undersized dunkers. Perhaps the most notable predecessors in this regard were David Thompson and Julius Erving (also known as Dr. J). Due to the relative lack of popularity of the NBA in the 70s, mainly because the NBA and the spinoff ABA were considered to be drug-addled and ‘too Black’ by broadcasters, these players did not get the requisite appreciation they deserved. In fact, the NBA finals was telecast on tape delay as recently as 1980, a mere four years before Michael Jordan got drafted. Incidentally, and perhaps not too surprisingly, Michael Jordan paid homage to David Thompson’s role in inspiring his style of play by choosing him as the presenter for his Basketball Hall of Fame induction ceremony.

6. Reinhart Koselleck, “Transformations of Experience and Methodological Change: A Historical-Anthropological Essay” in The Practice of Conceptual History: Timing History, Spacing Concepts, trans.Todd Samuel Presner et al (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002), 45-83.