Use-it-or-lose-it: A Proposal

Restrictive legislation around film copyrights is stopping a countless amount of titles from doing what they are meant to do: being watched

‘A film that isn’t screened is dead’ — thus spoke Henri Langlois, the famed programmer of the Cinémathèque Française where Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut and their contemporaries found their film education. Unfortunately, throughout the history of film, many people and organisations have done their utmost to ensure films go unscreened, utilising their status as the legal rights holders of a film to block or obfuscate its availability.

The Problem

When it comes to film history and its availability, most of the conversation turns on the material: the physical film print stored in an archive or discovered in an attic, alongside the digital transfer process, and the restoration quality. The restoration process has its own politics, ethics, and creative decisions, scrutinised and critiqued in plenty of places elsewhere. The materials, however, form only half of the equation. The other half, particularly as far as cinema history is concerned, is to do with the copyrights.

By and large, when an organisation wants to screen a film, or put it on blu-ray or on a streaming service, it needs to obtain the materials (a process made much easier if there is a digitised version of the film) and it needs to obtain the legal permission to show the film. Legal permissions are often split between the studio’s/production company’s rights, and the author’s rights (usually the director’s or the writer’s, or their offspring). As you might imagine, all of this costs money.

If you’re a film festival or repertory cinema programmer and you want to put together a complete retrospective of a director’s work, you need to obtain both the materials and the rights for every single title in the programme, a process even more arduous if the director went from studio to studio, leaving behind rights and materials in all manner of places. Mounting such retrospectives does become easier if a rights holder is actively willing to bring these films into visibility, or has an active relationship with the programmer. In practical terms, this kind of situation means that it will be easier to get a hold of the physical materials, and easier to negotiate reduced screening fees (most repertory bookings come with a fee charged for the copyright permission and/or the materials, including delivery, whether film or digital).

Many times, however, restorations and retrospectives are scuppered by the unwillingness of rights holders to play ball. Spend enough time around rep programmers and archivists, and you’ll eventually start to hear stories of the dream programme, blocked by an irate loser — often not the filmmaker but an heir, or a studio now run by people with no connection to the old work in their catalogue — crawling out of the woodwork with ridiculous, unaffordable stipulations and requests. The situation is even more intricate when you realise that material holders and rights holders are not necessarily the same people: a national archive like the BFI may well have a number of pristine prints sitting in its vaults, but not the rights to show them.

Reasons for refusal can be any number of things, and often are essentially anti-cinema and anti-art. Disney, for example, in the wake of their purchase of 20th Century Fox (and the vast array of titles included, which makes up a significant chunk of film history), has deliberately made it much more difficult to screen repertory titles. It comes down, of course, to a financial decision made by accountants who value growth above all else: any screen showing an old Fox title (or even an old Disney title) is one fewer screen available for the latest Disney film. This is the kind of thinking that only works at scale, in the long term, on a very big spreadsheet — even if it seems like nonsense right now that certain cinemas can no longer play ‘steady earners’. Counterintuitive this may be, especially when it comes to your own library, but withholding older titles makes financial sense if the endgame is domination of the media psychological landscape, where the only new films are safe, reliable, and IP-backed. Old films simply aren’t scalable at the same rate, lacking the cultural pull to hold the collective attention together — and it is that collective attention that brings in the most money. The same goes for TV shows: one only has to look at the withdrawal of series such as Westworld from the HBO Max streaming service, justified by not having to pay residuals to the creatives, as evidence of this philosophy elsewhere.

But it’s one thing for a corporation not to play ball — what about smaller studios and individuals, those with greater need for attention to their titles and the oxygen of publicity? Here, too, we can find difficult characters. A well-known example is Boris Eustache, the son of Jean Eustache, the legendary director of The Mother and the Whore (1973). Eustache’s work has been extremely difficult to see through legal means for decades, supposedly because Boris, the rights holder after Jean’s death, allegedly wanted an obscene amount of money for it — a fact that has only recently changed with the announcement of a restoration programme of Jean’s work. Whether Boris finally saw the light or someone finally met his demands, I have no idea. But in this time, his father’s reputation has slipped from the place it once occupied amongst all but hardcore cinephiles, the films largely existing on pirated copies. In the process, of course, Boris also left money on the table, because if the only viable way to see this work is via The Pirate Bay, then cinephiles will use The Pirate Bay.

The Solution

So how do we work around this often intractable problem, which unfairly consigns films and filmmakers to the dustbin of history? In the Marxist utopia of my head, copyright law does not exist, but in reality, sadly, it does. Allow me then to suggest some legislation which plays with the terms dictated by the modern neoliberal and capitalist world. This proposal still gives rights holders some leeway and financial compensation, but it also grants more agency to the cinephiles and film obsessives seeking to screen a title. What I propose is this: a use-it-or-lose-it clause that applies to all film copyrights.

The way this would work is simple: if an organisation or individual approached the rights holder and outlined in basic and flexible terms when they would like to screen the film, specifying the venue and its capacity, the rights holder would then legally have to say yes, unless they could offer a very good reason to refuse (more on that in a minute). There would be a flat fee — dictated by screen size — which the rights holder would be entitled to. And to keep a semblance of competition: the flat fee would be higher than the standard fee usually paid for repertory screenings, so as to encourage initiative and impetus from those rights holders who actually do want to bring their films into the public eye. Too many nos, and the rights would go into the public domain.

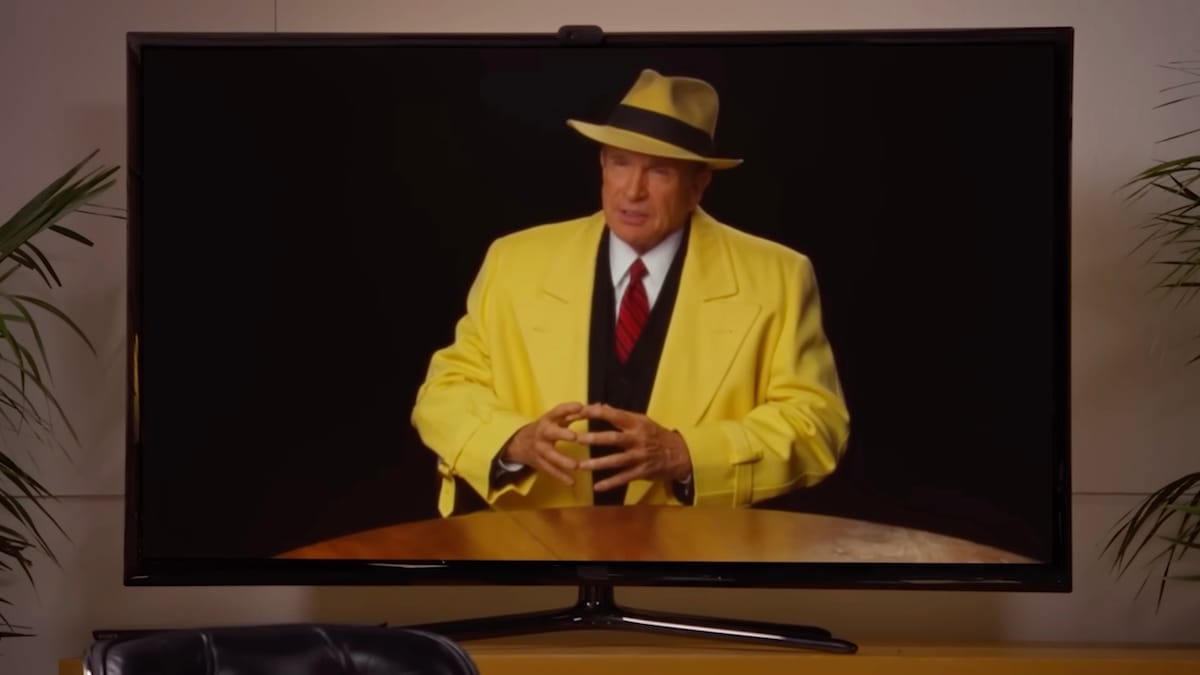

Use-it-or-lose-it rights are of course commonplace in many industries, and they are already present in film. The much-derided 2015 version of The Fantastic Four was made primarily because Fox was about to lose the rights to the characters (a problem Disney circumnavigated by flat-out purchasing Fox in 2019). Warren Beatty owns the rights to the Dick Tracy comic book character, and he wants to keep them. His contract with the original holders states that he must appear on TV as Dick Tracy once every number of years. Hence the bizarre sight of him appearing on TCM, in Dick Tracy get-up, purely as a sop to keep the rights. It is not uncommon that, when a book is optioned for the screen, the contract stipulates the film adaptation must be released in x amount of years, else the rights revert back to the author. So, use-it-or-lose-it as a concept already exists in several forms in cinema — why not apply it to rights after a film’s release? The rights holder must allow their film to be shown, for a reasonable financial recompense, or else they are deemed to be squatting on intellectual property and are therefore evicted.

“But won’t somebody please think of the rights holders?”, I can hear the bootlickers screaming. “Won’t they have legitimate reasons to block screenings?” Since I’m playing the capitalist game, I’ll follow through. Let’s think about potentially legitimate reasons to refuse a screening.

- “What if they’re concerned about their films being placed in a hate speech context?”

This is a mostly hypothetical situation, though I can imagine some neo-Nazis wishing to screen a Leni Riefenstahl film. If the rights holder has legitimate reason to believe their film may be used in a context that may promote hate speech, they can refuse the screening.

- “What if the request comes from an organisation whose values they don’t share?”

This one is arguably more likely. I have heard a woman director tell me she has refused her films to be screened at a Women’s Film Festival, on the basis that she wishes to be seen as a director and not as a woman director (and fair enough!). Likewise, perhaps a political party — or an organisation affiliated with a political party whose values a creator simply does not share — wishes to organise a screening of some of their work. This opens up a legal slippery slope. So much restoration work, and the legal untangling that follows it, is down to trust and good interpersonal relationships between archivists, curators, material holders and rights holders, and it’s usually this that brings a screening over the line when there’s resistance because of various personal or political anxieties. I don’t have a concrete answer here; perhaps the onus would be on the organisation to prove that their reasons for programming a film are primarily artistic, curatorial, or audience-led.

- “What if a restoration is planned and the rights holder wishes to keep older copies temporarily out of circulation so as to stress the ‘newness’ of the restoration when it arrives?”

This is where commerce and curatorial practice collides. All the major film festivals — Cannes, Berlin etc — have retrospective strands now, and they frequently request that the restoration of a film also premiere exclusively at said festival. A solution: if a rights holder turns down a screening because a new restoration is forthcoming, they have to show some proof of a restoration actually being planned or undertaken. There is a loophole: what if the restoration shown at a festival is never acquired by a distributor, and therefore never shown in the programmer’s country? Let’s say that all new films and new restorations have a set amount of time in which to obtain a traditional theatrical deal, alongside streaming, home release and all that. After that time, they will fall into the use-it-or-lose-it category.

- “What if the 35, 70, 16, or 8mm print of the film being requested is one of the last in existence, and the one on which a restoration would be based?”

A real issue: one cannot simply allow the last surviving print copy of a film to disintegrate because the rights holder has to say yes. But, as mentioned previously, the material copy and the legal rights are two separate things, frequently not housed in the same location at all. It is, I think, well within the material owners rights, particularly regards film itself, to refuse to lend out a copy they believe to be rare or fragile. Once a film has been digitised and available on DCP, this concern is moot, unless you specifically want to screen a print copy.

- “What happens if a production company goes bust?”

A depressingly frequent occurrence: a production company goes bust or shuts down, and their rights disappear into the ether of legalese. Sometimes a moneyed investor buys up the licences for their own shenanigans, but most often, nobody ever picks them up. In the case of author’s rights, an heir never shows up or engages with their legal right of inheritance. You can end up in the maddening situation where the print is pristine and ready to go, or the digital restoration is perfect, but it’s not possible to screen the film because nobody knows who actually owns the rights. In such an event of ‘lost’ or unclear rights, I would propose a national organisation whose sole purpose is simply to keep track of and register film rights, holding screening fees in escrow until a holder is found and whose role is partly to adjudicate on the issues brought up earlier. If no rightsholder is found after a reasonably short period of time (I’m willing to say as little as five years), those fees drop back into funding the organisation, and the film goes into the public domain. In the UK, the Intellectual Property Office is already in existence, and they do deal to an extent with these issues, but perhaps not to the level I’m proposing.

The Reality

How would all of this look in practice? I’m not stupid enough to presume I’ve covered all the bases or figured out how a cinephile’s heaven would look in legal reality. It’s entirely possible that, with the higher-than-standard flat fee, previously easy-going rights holders would suddenly adopt higher rates. That would then ensure that only well-endowed organisations could screen a great number of rep films, shutting out the vast legions of independent arthouses, small film festivals and community groups that create such energy out of highly selective programming. Would rights holders find loopholes as often as possible to refuse screenings, or stretch out restoration plans across decades, like Warren Beatty in his Dick Tracy outfit? I can’t answer any of that; this proposal is likely to never come to fruition, and even if it did, it would be in highly watered-down form. But it’s good to think, consider, and dream about what such a future might look like where greed would not let film history languish in obscurity.